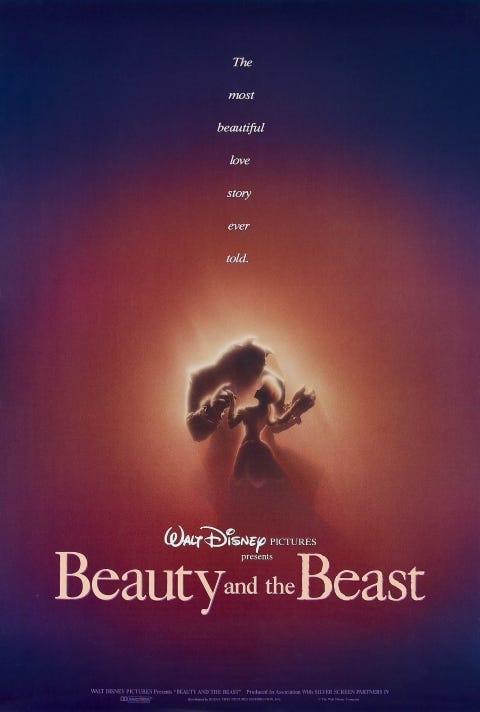

On September 29, 1991, The Walt Disney Company did something unprecedented. They screened an unfinished workprint of their upcoming film, Beauty And The Beast, at the New York Film Festival. This was a risky and unusual move for a number of reasons. While test screenings had long been a part of the process, festival audiences were different, particularly this festival. NYFF was (and is) one of the most highly regarded festivals in the country. It had introduced American audiences to works by Truffaut, Godard and Kurosawa. In 1991, the opening night film had been Krzysztof Kieslowski’s The Double Life Of Veronique. This was not a crowd predisposed to enjoying an animated Disney movie.

But Jeffrey Katzenberg wanted to show the world that Beauty And The Beast was not your typical Disney cartoon. While The Little Mermaid had been hailed as an instant classic, The Rescuers Down Under had been seen by most as a lateral move at best, if not a slight step backward. Katzenberg needed people to know that The Little Mermaid was no fluke. And so, he presented a movie that was only about 70% complete to one of the toughest audiences in the world.

Interestingly, this was not Disney’s first attempt at drumming up excitement by courting the NYFF crowd. In 1982, Tim Hunter’s Tex screened at the festival. Two years later, Touchstone’s Country, directed by Richard Pearce, was the opening night film. But this time, it worked. The NYFF audience greeted Beauty And The Beast with a rapturous standing ovation. It was the clearest sign yet that Disney Animation was entering its second golden age.

Walt himself had tried to adapt Beauty And The Beast a few times, with efforts dating back to the 1930s. The project was ultimately abandoned after the story department failed to crack the nut. There are also those who believe that Walt lost interest in adapting the tale after seeing Jean Cocteau’s brilliant 1946 version. That would make a certain amount of sense. It wouldn’t have been the first time Walt was put off by having to settle for second place.

In the late 1980s, Disney approached Richard Williams, the animation director on Who Framed Roger Rabbit, about tackling Beauty And The Beast. Williams wanted to get back to work on his own passion project, the decades-in-the-making The Thief And The Cobbler, and declined the offer. Instead, Williams recommended his friend Richard Purdum, who ran a successful commercial animation studio in England. Producer Don Hahn and a small group of artists flew over to London to begin work with Purdum.

After about six months, the team returned to Burbank to show Jeffrey Katzenberg and Michael Eisner what they’d come up with. Katzenberg scrapped all of it, instructed Hahn and his team to start from scratch and let Purdum go. He also approached Howard Ashman and Alan Menken, the songwriting team from The Little Mermaid, about lending their talents to the project. At first, Ashman wasn’t all that interested. He had his own pet project, Aladdin, that he and Menken had been working on. But Katzenberg and Eisner weren’t entirely sold on Aladdin yet. With a little cajoling, they persuaded Ashman and Menken to switch gears to Beauty And The Beast.

As on The Little Mermaid, Ashman took a key role in shaping the film’s story and production. While Purdum had envisioned a darker take without songs, Ashman turned it into a full-on Broadway-style musical with multiple production numbers. He also insisted that casting be done out of New York, resulting in a roster of theatre veterans like Paige O’Hara, Richard White, Jerry Orbach and, of course, Angela Lansbury, back at Disney for the first time since Bedknobs And Broomsticks. Even Robby Benson, the voice of the Beast, had a musical theatre background that surprised many who only knew him as a teen idol of the 1970s.

With Purdom gone, the project needed a new director. After Ron Clements and John Musker, the directors of The Little Mermaid, passed, a provisional offer went out to Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale. Wise and Trousdale were both young and had never directed a feature before. But they’d made an impression on Cranium Command, a new attraction at Epcot. Hedging his bets a little, Katzenberg made them “acting directors” on the project, giving himself an easy out in case they failed to deliver. But Wise and Trousdale more than lived up to the task and, after a few months, their unofficial probationary status was lifted.

Katzenberg also insisted that the animators work from a proper screenplay this time instead of the usual mix of treatments and storyboards they were used to. He hired Linda Woolverton, a YA novelist who’d been toiling away for years writing for such TV cartoons as Dennis The Menace, Ewoks and Teen Wolf. Woolverton had a hard time adjusting to the Disney Method at first, resulting in a few conflicts when the animators would change the script. Things became easier once she was brought into the process and learned how the sausage was made, so to speak. She’d continue to be a Disney fixture for years.

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about Beauty And The Beast is how seamlessly all of these elements blend together. This does not feel like a movie assembled by committee although, in some ways, that’s exactly what it is. There’s no one person you can point to and say that’s the one who made Beauty And The Beast what it is. But it became a passion project for every single person who worked on it. It’s a stunning example of collaborative art.

The film’s opening number, “Belle”, serves as a statement of purpose. The song is a remarkable piece of musical storytelling, setting up so much character and story in a brisk and lively five minutes. The animation is fluid and alive with each shot crammed with so many details, it’s impossible to catch them all in one viewing. It’s a masterful sequence that most movies would have a hard time topping. And yet, Beauty And The Beast continues to out-do itself from there. It’s genuinely funny, achingly romantic and absolutely beautiful to look at from start to finish.

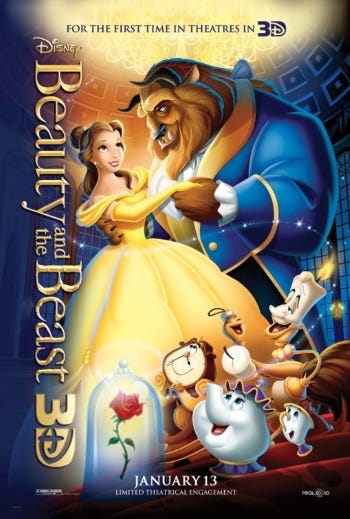

Following its triumphant appearance at the New York Film Festival, Disney opened the completed film in limited release on November 13, 1991, before expanding on November 22. It never quite made it all the way to the top of the box office chart, held off by a variety of other holiday releases, primarily Steven Spielberg’s Hook. Nevertheless, it was a massive hit, grossing over $145 million and becoming one of the biggest movies of 1991.

Critics unanimously praised the film as a masterpiece. The biggest surprise came on February 19, 1992, when Beauty And The Beast became the first animated film ever nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards. This was also the first Disney movie to be up for the award since Mary Poppins (although a Touchstone movie had been a few years earlier). It received five additional nominations, three of them in the Best Original Song category alone. The winning song was “Beauty And The Beast”, beating out “Belle” and “Be Our Guest” (not to mention “(Everything I Do) I Do It For You” from Robin Hood, Prince Of Thieves and “When You’re Alone” from Hook). Alan Menken also won for Best Original Score.

Menken’s victory and acceptance speech was understandably bittersweet. His musical partner, Howard Ashman, never got to see the finished film. In 1988, he’d been diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. Ashman kept this private for as long as he could and continued to work. As the disease worsened, work on Beauty And The Beast moved closer to his home in New York so he could receive treatment. Howard Ashman died on March 14, 1991, at the much too young age of 40. In 2001, he was posthumously inducted as a Disney Legend.

Many reviews of Beauty And The Beast compared it to the best musicals Broadway had to offer. A few years later, Disney put that claim to the test by debuting a stage version. The show was a smash, running for over a decade in New York and kicking off a new revenue stream for Disney. Since then, Disney Theatrical Productions has adapted everything from Mary Poppins and Freaky Friday to High School Musical. As of January 2025, The Lion King and Aladdin are still on Broadway while Beauty And The Beast will be kicking off a new tour this summer.

In 1997, Belle and the Beast returned in the direct-to-video sequel Beauty And The Beast: The Enchanted Christmas. This was actually one of the better Disneytoon productions (which is admittedly a pretty low bar). It was to be followed by an animated TV series. When Disney decided against going forward with the show, the few episodes that had been produced were stitched together and released as Belle’s Magical World.

The Disney Channel did produce one TV series based on the film. Sing Me A Story with Belle featured Lynsey McLeod as a live-action Belle, now the owner of the village bookshop, singing and narrating stories to the local children with accompanying animation from vintage Disney cartoons. This was incorporated into the third and final direct-to-video release, Belle’s Tales Of Friendship. None of these follow-ups held a candle to the original, of course, but they could have been a lot worse.

Beauty And The Beast remains a minor miracle of a movie. It’s the perfect showcase for a new generation of Disney animators working at the peak of their abilities. It’s arguably the best score ever written by the powerhouse team of Howard Ashman and Alan Menken. Everything came together to create a film as close to perfection as Disney had produced in decades. The Disney Renaissance was now in full bloom.

VERDICT: Disney Plus

I recall that the work print was released on laserdisc before the finished film was, another unprecedented move. It was a thrill to be able to watch it at home, even though it was unfinished. IIRC the soundtrack was completed. Movies did not move to home video as quickly in those days as they do now.