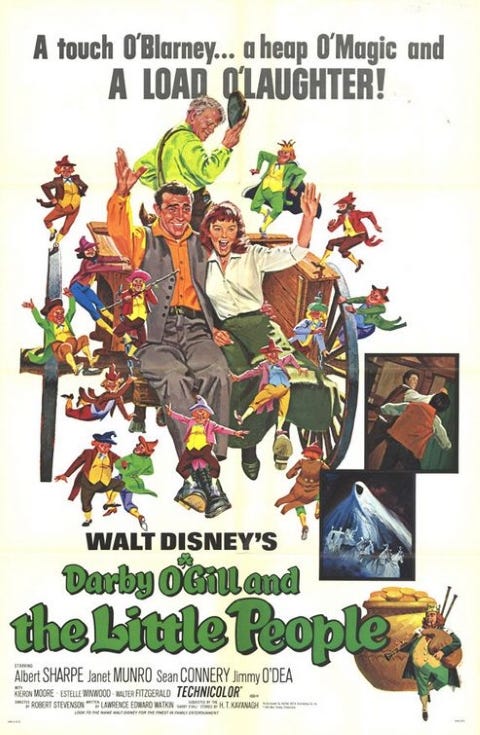

As a rule, Walt Disney did not spend nearly as much time developing his live-action features as he did his animations. He’d settle on a subject, assign it to a writer, assemble a cast, shoot the thing and get it out to theatres in a relatively short period of time. 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea posed some technical challenges that lengthened the production period but Earl Felton and Richard Fleischer still put the script together quickly. The project that evolved into Darby O’Gill And The Little People was an exception, with over a decade elapsing between Walt’s original concept and its eventual release in June 1959.

Walt made his first trip to Ireland in 1947. While there, he got in touch with his family’s Irish roots (tenuous and distant as they may have been) and decided he wanted to make a movie about leprechauns. Lawrence Edward Watkin, the screenwriter responsible for Disney’s UK productions of the early 50s, produced a script called Three Wishes which would have combined live-action and animation. By 1956, it had turned into The Three Wishes Of Darby O’Gill, based on the stories by Herminie Templeton Kavanagh. Walt and Watkin returned to Ireland, soaking up the atmosphere and researching Irish folklore. By early 1958, casting was underway on the newly retitled Darby O’Gill And The Little People.

Originally, Walt wanted Barry Fitzgerald, the Oscar-winning Irish star of Going My Way, to play both Darby O’Gill and Brian, King of the Leprechauns. But Fitzgerald felt he was getting too old to take on such a challenging workload and passed. In his place, Walt cast Albert Sharpe as Darby. He’d seen Sharpe perform in the Broadway production of Finian’s Rainbow and kept him in mind as a backup in case Fitzgerald turned him down. But Sharpe had essentially retired by the time Walt got around to making the movie and had to be talked into doing the role. He’d appear in one more film, the 1960 caper movie The Day They Robbed The Bank Of England, before retiring for good.

For King Brian, Walt abandoned the dual-role gimmick and cast Jimmy O’Dea, a popular star of Irish stage and radio. O’Dea was most famous for his character Mrs. Biddy Mulligan, a working-class street vendor, who he performed on stage and a series of records. After Darby O’Gill, O’Dea had the opportunity to immortalize the Biddy Mulligan character on camera for his sketch comedy TV special, The Life And Times Of Jimmy O’Dea, before his death in 1965.

Amusingly, Walt tried to sell audiences on the idea that he had cast actual leprechauns in the film. The movie opens with a personal note that reads, “My thanks to King Brian of Knocknasheega and his Leprechauns, whose gracious co-operation made this picture possible.” He’d take the gag a step further with I Captured The King Of The Leprechauns, an episode of Walt Disney Presents promoting the movie. In the episode, Walt travels to Ireland to personally meet with O’Dea (as King Brian) and persuade him to appear in the picture. If nothing else, you’ve got to give Walt credit for finding fun and novel ways to sell his empire.

Although the film would be shot in southern California, casting took place in London. It was there that Walt spotted Janet Munro, an ingenue in her early 20s. Munro had appeared in a couple of films, including the B-horror movie The Trollenberg Terror (better known in the States as The Crawling Eye), but had mostly worked in television. Walt saw her on an episode of ITV Television Playhouse and called her in for a screen-test. Munro has a wide, infectious smile and a no-nonsense attitude that makes her perfect for the role of Darby’s daughter, Katie O’Gill. Walt liked her so much that he made her part of the Disney Repertory Players, signing her to a five-year contract. She’ll be back in this column.

Walt did not offer a contract to Munro’s leading man, a tall Scotsman named Sean Connery. Connery had been trying to break into the movies for a few years, landing mostly bit parts in forgettable thrillers like No Road Back and Action Of The Tiger. His biggest role to date had been in the 1958 melodrama Another Time, Another Place opposite Lana Turner. That movie made him the target of Turner’s jealous gangster boyfriend, Johnny Stompanato, but didn’t do much for his career. When the Darby O’Gill offer came along, Connery was in no position to pass it up, even though it required him to sing, which he was not excited about, and attempt to transform his Scottish accent into an Irish brogue.

There are rumors that Connery’s and Munro’s singing voices were dubbed by others. That’s certainly possible. That practice was commonplace back in the 50s and 60s. But Connery also sings a little bit in Dr. No and his voice sounds identical in that movie as it does here, so I’m inclined to give him the benefit of the doubt. His Irish brogue, however, is less convincing. The next time he played an Irishman, in his Oscar-winning role in The Untouchables, he wisely didn’t even bother trying.

Connery was not the breakout star of Darby O’Gill. That honor went to Janet Munro, who won the Golden Globe for Most Promising Female Newcomer. Connery was described as “merely tall, dark and handsome” by The New York Times and the film’s “weakest link” by Variety. But his performance did catch the eye of producer Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli, who had recently acquired the film rights to Ian Fleming’s James Bond. Broccoli liked Connery and brought his wife, Dana, to another screening of Darby O’Gill to get her opinion. Dana wholeheartedly believed that Connery had the right stuff to be Bond and the rest is history. So even though Connery didn’t land a Disney contract, things seemed to work out all right for him.

The director was Robert Stevenson, making the third of his many Disney features following Johnny Tremain and Old Yeller. Darby O’Gill required a lighter touch than had his previous films for the studio and Stevenson acquits himself well. The pub sequences with Darby regaling the townsfolk with tales of his adventures with King Brian are full of character and warmth. Stevenson doesn’t bother with a lot of traditional exposition. Rather, we’re allowed to fill in the blanks and get to know the characters and their relationships to one another in our own time.

This was also the most technically challenging film Stevenson had attempted to date. Convincingly bringing the leprechauns to life required a combination of practical effects and visual trickery courtesy of the great Peter Ellenshaw. Ellenshaw and cinematographer Winton Hoch employed forced perspective to create the illusion that Darby was interacting with the 22-inch-tall King Brian. Disney’s Imagineers had been using similar tricks with forced perspective throughout Disneyland. It’s the technique that makes Sleeping Beauty’s Castle appear to be a whole lot bigger than it really is.

The Disney studio only had one soundstage big enough to accommodate the oversized sets and enormous lights the work required. But Stage 2 was in constant use by the TV division, so Disney constructed a massive new soundstage, Stage 4. (Stage 3 and its water tank had been built a few years earlier for 20,000 Leagues.) In 1988, it would be divided in two, Stage 4 and Stage 5, where it would become the home of various TV shows like Home Improvement.

All the new construction and work paid off. The illusion of the leprechauns is completely convincing to this day. Even when you know how it was done, there are shots of Darby sharing the screen with the leprechauns that have you blinking your eyes in disbelief. That’s the difference between special effects and optical illusions. You can dissect a special effects shot and see how it was built. Optical illusions are seamless no matter how many times you’ve seen them.

The leprechauns aren’t the only characters from Irish folklore brought to life by special effects. Darby’s horse transforms into a púca. Later on, the banshee appears and summons the death coach to claim Katie. These optical effects haven’t aged as well but they work beautifully within the context of the film. When I was a kid, the banshee scared the bejeezus out of me. Needless to say, I absolutely loved the banshee.

Stevenson allows the story to unfold at the leisurely, rambling pace of a good yarn spun in a warm and inviting Irish pub. The heart of the story is the relationship between Darby and King Brian. It’s an equally matched battle of wits. They’re both clever, a little conniving and fond of a nip from the jug now and again. In a lot of ways, it’s Disney’s first buddy comedy.

The love story between Munro and Connery isn’t quite as convincing. Munro does her part, lighting up the screen with her smile and gradually warming to the young man in line to take her father’s job as caretaker. But Connery doesn’t seem all that interested in her. He does a great job early on as he wonders what exactly he’s gotten himself into by accepting this gig. But his attraction to Munro happens in an instant, like a switch has been pulled.

The supporting characters are a lot of fun, especially Estelle Winwood as the Widow Sugrue and Kieron Moore as her son, Pony. The widow aims to install Pony in Darby’s old job and as Katie’s husband. Winwood’s great juggling her two-faced nature. One moment she’s too sweet and too helpful. The next, she’s hustling into town to give Pony his marching orders. This would be Winwood’s only Disney film in a long career that reached back to the 1930s. She’d later have memorable appearances in The Producers and Murder By Death before her death in 1984 at the age of 101.

The bullying, somewhat dense Pony always does exactly what his sainted mother tells him to do, even though he doesn’t fully believe that things are going to work out the way she thinks. Moore is kind of like a flesh-and-blood version of Gaston in Beauty And The Beast. He’d go on to appear in such films as The Day Of The Triffids and Son Of A Gunfighter before becoming a documentarian and social rights activist in the early 1970s.

Darby O’Gill And The Little People did reasonably when it came out but it wasn’t a huge hit. Compared to the millions raked in by the low-budget The Shaggy Dog, the lavish Darby O’Gill was considered a disappointment. But in the years since, it has become something of a cult movie. Its ingenious special effects and the winning performances of Sharpe, O’Dea, Munro, Moore and the early star-making turn by the legendary Sean Connery have all kept it alive in the memories of its fans. It’s just a little bit darker and a little bit more grown-up than some of Disney’s other live-action productions but not so much that people don’t feel comfortable sharing it with their kids.

So far, Disney has resisted the urge to produce a sequel or a remake of Darby O’Gill. Good. This is by no means a perfect movie but it is a perfectly charming one. Replicating the unique magic that makes it special would require a very careful hand. Disney’s current filmmaking-by-committee approach to most of its reboots does not suggest they’d be capable of such a task. Better to leave Darby O’Gill And The Little People in Walt’s imagined SoCal Ireland.

VERDICT: Disney Plus

Dedicated to Sir Sean Connery

The banshee terrified me when I was a kid also.