Disney Plus-Or-Minus: Lady And The Tramp

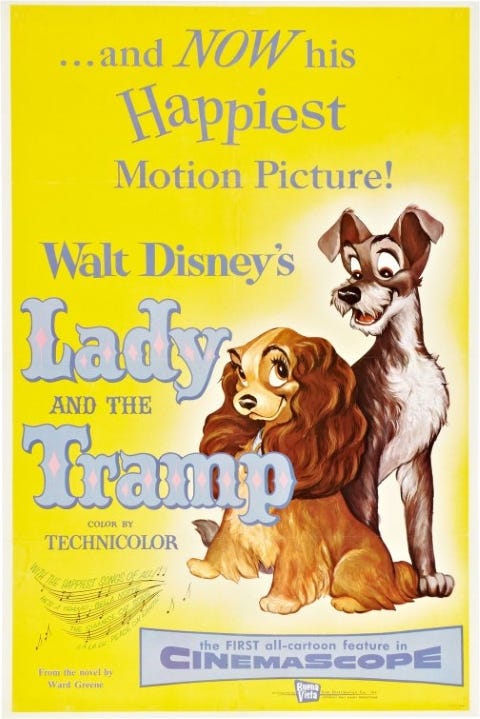

When Lady And The Tramp debuted on June 22, 1955, it should have been a bigger deal. For years, the Disney name had been synonymous with feature animation. Here was the studio’s first feature cartoon since Peter Pan two years earlier. Not only that, it was the first ever produced in CinemaScope. But animation had become almost an afterthought at the studio. Walt himself had decided it was time for his name to become synonymous with something much bigger. His attention was entirely on Disneyland. Lady And The Tramp would have to sink or swim on its own merits.

Lady And The Tramp is easily one of Disney’s most unusual feature animations. For the first time, the story was entirely self-generated and not based on a classic fairy tale or book. Development began all the way back in 1937 when animator Joe Grant brought in some sketches he’d done of his English Springer Spaniel, Lady. Grant had just had a baby and his sketches of the jealous Lady made Walt think there might be a story there. He assigned a small group of storymen to the project and work quietly began on Lady.

By 1945, work on Lady hadn’t progressed much farther than that. Various artists and storymen dropped in ideas here and there but it simply wasn’t coming together. The project might have disappeared into the vault if Walt hadn’t come across a short story in Cosmopolitan magazine called “Happy Dan, The Cynical Dog”. Walt decided a scrappy, cynical dog might be just the counterpoint the sweet, lovable Lady needed.

Walt already knew the story’s author. Ward Greene was a writer and journalist but his day job was general manager of King Features Syndicate, distributing columns and comic strips to newspapers around the country. Disney had been a staple of the funny pages and a feather in King Features’ cap since the Mickey Mouse comic strip premiered in 1930. Odds are this was not a difficult negotiation.

Work continued on what would eventually be titled Lady And The Tramp off and on for the next several years, mostly off. Joe Grant left the studio (and animation, at least temporarily) in 1949, leaving the story to be molded primarily by Ward Greene. Still, the project was simply not a priority at the studio.

Finally in 1953, Walt and Roy Disney had a problem. For years, they had struggled with having too many animated projects in various stages of development. Now, for the first time, they didn’t have enough. Peter Pan had been released but Sleeping Beauty, intended to be Walt’s magnum opus, was nowhere near finished. Roy was in the process of launching Buena Vista, the studio’s new distribution arm. It would be a lot easier to woo exhibitors to Disney distribution with the promise of new Disney animation.

According to Neal Gabler’s excellent book Walt Disney: The Triumph Of The American Imagination, Walt first considered simply cobbling together another package film. That would have been easier said than done, since the production of animated short subjects was trickling to a halt. Any animators not working on Sleeping Beauty had been kept busy producing new but cheap footage for the Disneyland TV series and The Mickey Mouse Club. Instead of a package film, Roy encouraged Walt to kickstart Lady And The Tramp, figuring it would be a relatively quick and easy project to complete.

It probably would have been except for one thing: CinemaScope. The widescreen process had become Hollywood’s latest craze toward coaxing audiences away from televisions and back into theatres. Disney had successfully used it on the live-action 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea and the Oscar-winning animated short Toot, Whistle, Plunk And Boom. When he decided to shoot Lady And The Tramp in CinemaScope, the animators had to make some big adjustments. The backgrounds had to be bigger. Layouts had to be changed. They even had to prepare a second, alternate version formatted for theaters that weren’t equipped to project CinemaScope. Consequently, the “quick and easy” project took longer to complete than anticipated.

Narratively, Lady And The Tramp remains true to the modest goals first laid out by Joe Grant. The story opens on Christmas with Jim Dear presenting Lady in a hatbox as a gift to his beloved wife, Darling. This incident, supposedly inspired by Walt’s own Christmas gift of a puppy to his wife, Lillian, early in their marriage, helped obfuscate Grant’s contribution to the story in later years. Opening with such a personal moment, everyone simply assumed the story was Walt’s and Walt himself did little to suggest otherwise.

The movie ambles along at its own pace from there, following Lady as she grows up, gets to know her neighbors Jock and Trusty, acquires her collar and official dog license. The movie’s almost a third over before we’re introduced to either the idea of a new baby entering the home or even Lady’s costar, Tramp.

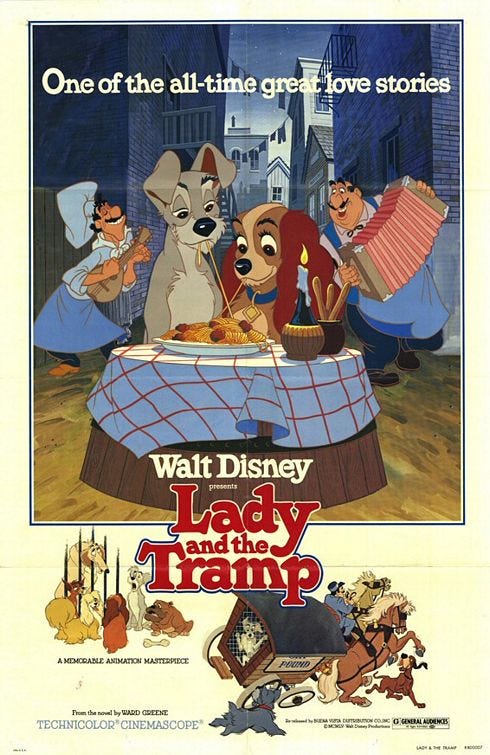

Lady And The Tramp has a reputation as one of the most romantic movies of all time, animated or otherwise. It landed at Number 95 on the American Film Institute’s 2002 list of love stories, 100 Years…100 Passions. But the film takes its time revealing that side of itself. Crucially, Disney spends the first 45 minutes or so romanticizing the characters’ world rather than the characters themselves. Tramp and his friends from the wrong side of the tracks are kept separate from Lady and her Snob Hill neighbors. Both worlds seem equally appealing and idyllic on their own. When Lady and the Tramp come together, they blend into a singular, magical space.

After Disneyland opened, it became common shorthand to compartmentalize Disney’s work into the four park areas: Fantasyland, Adventureland, Frontierland and Tomorrowland. But there was always a fifth area to the park, Main Street USA, and it’s that idealized, hyper-nostalgic worldview that’s on full display in Lady And The Tramp.

More often than not, Disney would indulge his nostalgic impulses through live-action films like So Dear To My Heart and later, Pollyanna. Lady And The Tramp translates that live-action aesthetic into animation and the result is even more idealized. We believe in the somewhat unlikely romance between these two dogs in large part because of their perfect surroundings.

Supposedly, Walt was ready to cut the now-iconic spaghetti dinner scene, concerned that the sight of two dogs wolfing down a big plate of pasta would just look ridiculous. Animator Frank Thomas fought for it, animating the whole thing by himself to prove his point. The beautifully animated scene kicks off the “Bella Notte” sequence, a lovely blend of character animation, sumptuous backgrounds and romantic details. How could anyone not fall in love to images like these?

Their happiness is short-lived as Lady is thrown into the local dog pound, where she learns some harsh truths about her new boyfriend. Tramp gets around and everybody’s got a story to tell about his love life. By the time she gets sprung from lockup, Lady’s fed up with Tramp. He ran off and abandoned her when she was caught. Now it seems he never really cared about her at all.

But Tramp hasn’t abandoned Lady or run away. He’s completely selfish but he isn’t a coward. We’ve already seen that he’s got a soft spot for puppies and is a true and loyal friend, rescuing dogs on their way to the pound. He assumed that Lady would be fine, thanks to her get-out-of-jail-free license. As soon as she’s out, he comes by to check on her and learns that love means putting another person (or dog or, in this case, baby) ahead of your own best interests. As relationship lessons go, the ones taught by Lady And The Tramp aren’t bad.

For the voice talent, Disney cast a wider net than on other projects, recruiting a number of actors from outside the studio. Barbara Luddy provided the voice of Lady. It was her first role for Disney but not the last. She’d go on to voice a number of characters over the years, including Kanga in the Winnie The Pooh series. Tramp was voiced by Larry Roberts, a stage performer who never made another film. He retired from show business in the late 1950s and went into fashion design. Reliable Disney stock players Verna Felton and Bill Thompson appeared as Aunt Sarah and Jock.

Disney even brought in a pair of voice talents not typically associated with the studio. Stan Freberg was an established voice talent at Warner Bros. and on radio who was beginning to hit the big time with his own comedy records when Disney brought him in to provide the voice of the Beaver. Alan Reed was still a few years away from landing his defining role as Fred Flintstone but was a popular radio and character actor when he voiced Boris, the Russian wolfhound.

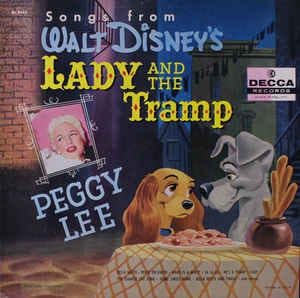

But the not-so-secret weapon of Lady And The Tramp is undoubtedly Miss Peggy Lee. Disney had never relied on celebrity voices for his cartoons but he certainly wasn’t against using them. Bing Crosby and Basil Rathbone had toplined The Adventures Of Ichabod And Mr. Toad and Alice In Wonderland’s Mad Hatter was modeled after radio star Ed Wynn. But Peggy Lee was in a different category when she arrived on the Disney lot.

Peggy Lee became the singer in Benny Goodman’s orchestra in 1941. Within two years, she had the number-one song in the country, the million-selling “Why Don’t You Do Right?” After she left Goodman’s group, her career really took off with huge hits like “Golden Earrings” and “Mañana (Is Soon Enough for Me)”. Her being asked to work on Lady And The Tramp was the 1950s equivalent of Elton John working on The Lion King or Phil Collins on Tarzan.

Peggy Lee gave the work her all. She provides the voices for four characters: Darling, the cats Si and Am and, of course, Peg the Pekingese. She even gave story notes. Trusty the bloodhound was supposed to die at the end until Peggy Lee cautioned against traumatizing a generation that was still grieving Bambi’s mom.

Most importantly, she collaborated with Sonny Burke on six original songs. Burke had first worked for Disney on Toot, Whistle, Plunk And Boom and he’d go on to produce some of Frank Sinatra’s most iconic records, including “My Way”. The songs Lee and Burke wrote for Lady And The Tramp work perfectly with Oliver Wallace’s Victorian-tinged score. The lullaby “La La Lu” bridges the gap between the eras nicely.

But the songs everyone remembers from Lady And The Tramp are distinctly modern. “Bella Notte”, “The Siamese Cat Song” and “He’s A Tramp” are very much of their era. They help contemporize Lady And The Tramp, bringing it out of the rose-colored mists of nostalgia and into the present day. Today, it creates a feeling of double-nostalgia for both Walt’s turn-of-the-century youth and for the 1950s. It’s the same powerful feeling that accounts for the continued popularity of movies like Grease. We’re nostalgic for nostalgia itself, not for a specific era.

As for “The Siamese Cat Song”, it’s a bit lame to brush aside its casual ethnic stereotyping by saying that this is far from the worst example of it we’ll see in a Disney movie. Sure, they’re cats but there’s no missing the implications of the character design, music or voices. One can certainly understand why the song was scrapped from the recent Disney+ remake. Still…it’s a good song. The Asian pastiche is a pretty common type of popular song and this is one of the better examples of it.

Besides, it isn’t like the cats are singled out. It’s a long-standing tradition in animation that if an animal can be defined by an ethnic stereotype, it will be. Jock, the Scottish terrier, is very Scottish. Boris, the Russian wolfhound, is very Russian. Pedro, the chihuahua, is very Mexican. Of course Si and Am are going to be very “Siamese”, which is a word that people just took to mean generally Asian back in the day. At least they weren’t called “Oriental”. On our ongoing list of Outdated Tropes of the Past, “The Siamese Cat Song” doesn’t seem worth getting too worked up over.

Lady And The Tramp was not an immediate hit with critics. Many longtime Disney supporters dismissed it as sentimental and inconsequential. But audiences loved it. It quickly became the studio’s biggest hit since Snow White, ending up as the sixth highest grossing film of 1955.

Lady And The Tramp didn’t exactly lend itself to Disneyland attractions or toys and games beyond the usual merchandise but its popularity earned it a spin-off comic strip. Scamp, originally written by Ward Greene and distributed by King Features, followed the adventures of Lady and the Tramp’s mischievous son for over 30 years. The strip finally ended in 1988 and Scamp returned to animated form in the 2001 direct-to-video sequel Lady And The Tramp II: Scamp’s Adventure.

Even today, Lady And The Tramp remains one of Disney’s most popular films. In 1987, the film was released on VHS for the first time and surprised everyone by becoming the best-selling videocassette of all time. Perhaps nobody was more surprised than Peggy Lee, who sued Disney for royalties on the video sales. She was eventually rewarded over $2 million and the case changed entertainment copyright law forever, forcing studios and unions to grapple with new media like home entertainment.

Lady And The Tramp proved that Walt Disney didn’t need a beloved book or fairy tale to deliver a heartfelt, masterfully animated feature. The studio was more than capable of crafting their own stories. But unfortunately, it came around a little too late. Walt had almost done everything he wanted to accomplish with animation. His heart and his mind now belonged to Disneyland. The golden age of Disney animated features was coming to a close.

VERDICT: Disney Plus.