Disney Plus-Or-Minus: One Hundred And One Dalmatians

By 1961, Walt Disney Animation Studios was a shadow of its former self. Their last feature, Sleeping Beauty, had been a costly failure at the box office. As a result, a wave of layoffs swept the organization. The short films, which had once been the studio’s bread and butter, had all but been eliminated. The shorts division had been shut down in 1956 and its work folded into the feature division. At its peak, the studio had been releasing more than a dozen shorts a year. Now they were lucky to release two or three. What little animation Disney was producing was mostly for TV.

Walt couldn’t have mounted another ambitious production like Sleeping Beauty even if he’d wanted to. Sadly, it was becoming increasingly evident that he really didn’t want to. The failure of Sleeping Beauty left him within a hair’s breadth of shutting the animation division down completely. Only a sense of loyalty to the medium he’d helped shape kept it afloat. That same sense of tradition would continue to keep animation alive at the studio in lean times to come. A Disney studio without cartoons would be like a McDonald’s without hamburgers.

For feature animation to continue to have a place at Disney, changes had to be made. The labor-intensive, impeccably detailed house style needed to be streamlined. Walt had seen more than a few animated features lose money, so the process had to be made more cost-effective. Even the sensibility that relied on fairy tales and timeless classics needed to be updated for the second half of the twentieth century. What the studio needed turned out to be puppies.

British author and playwright Dodie Smith published her novel The Hundred And One Dalmatians in 1956. Walt read it not long after and fell in love with it. He bought the rights (much to the delight of Ms. Smith, who had kind of hoped Disney might make it into a movie) and immediately made it a priority. This decisiveness was somewhat unusual for Walt. It wasn’t unheard of for him to take years waffling back and forth on which project to tackle next. It was the first of many changes to come.

Previous animated features had employed teams of storymen, who would hash out every plot point and gag in minute detail. For Dalmatians, Walt assigned the writing job to just one man. Bill Peet had joined the studio in 1937 as an in-betweener, working on Donald Duck shorts and Snow White. He worked his way up to the story department, where he quickly earned a reputation as the best of the bunch. If anyone was capable of doing the job solo, it was Bill Peet.

Peet turned in his draft just two months later, making some significant changes to streamline Smith’s book. He eliminated the character of Cruella De Vil’s husband. He also combined two of the dogs, Missis and Perdita, into one. In the book, Missis is Pongo’s mate and the mother of the puppies. Perdita is a stray that the family adopts and acts as a nurse.

Walt thought Peet’s script was terrific and set him to work storyboarding the film. Again, this would be the first time that a single artist was responsible for storyboarding an entire feature by himself. But at the same time, they still had to solve the problem of animating all those unique, spotted dogs without spending a fortune.

Walt’s old partner Ub Iwerks, who had rejoined the studio in the visual effects department, came up with the solution. He had been experimenting with a Xerox camera to develop a way to transfer animators’ drawings directly onto cels, eliminating the need for hand inking. The process had been used successfully on the climactic sequence of Sleeping Beauty and on the short film Goliath II, also written by Bill Peet. Art director Ken Anderson proposed using Xerography on Dalmatians to Walt. Walt, who had lost interest in the nuts and bolts of animation by now, replied with a shruggy, “Yeah, you can fool around all you want to.”

The process worked, saving a fortune in production costs, but it had its limitations. By eliminating the inking stage, the finished animation looks rough and scratchy compared to the typical Disney style. Walt wasn’t a fan. He missed the smooth, perfect look of his previous films. The animators, on the other hand, loved it. They had long complained that the ink-and-paint department used a heavy hand on their work. For the first time, they were seeing exactly what they drew on the screen.

Bill Peet made another clever change to the book that would help cement One Hundred And One Dalmatians’ place in the Disney canon. In the book, Pongo’s pet (named Mr. Dearly) is basically a glorified accountant. He’s referred to as a “financial wizard” but his job doesn’t have much bearing on the story. In the film, Mr. Dearly becomes Roger Radcliffe, a struggling songwriter. This allows for some natural, unobtrusive ways to incorporate a few original songs by Mel Leven.

Leven was new to the studio but he’d already proven himself as a songwriter for Peggy Lee, the Andrews Sisters and other popular acts. He’d done some work at rival animation house UPA before landing at Disney. There are only three songs in One Hundred And One Dalmatians. Two of them, “Dalmatian Plantation” and the great “Kanine Krunchies Kommercial”, are so short that they barely register as musical numbers. But the third, “Cruella De Vil”, belongs on any shortlist of Disney’s all-time great original songs. It’s so good that you even buy the fact that it becomes a hit song in the movie itself, even though Roger would surely be opening himself up to a lawsuit. Cruella definitely seems like she would be litigious.

The vocal cast was a mixed bag of newcomers and Disney veterans. Rod Taylor, who scored a big hit with George Pal’s The Time Machine in 1960, provided the voice of Pongo. Cate Bauer, a stage actress who made very few appearances in film or television, was cast as Perdita. The voices of their human pets, Roger and Anita, were provided by Ben Wright and Lisa Davis. There are really two love stories at the heart of the film and if either one of them didn’t work, the entire movie would suffer. But the vocal performances sell us on these relationships and they align beautifully with the naturalistic, easygoing animation. Of the four, only Ben Wright will be back in this column.

Betty Lou Gerson had been the narrator of Cinderella but she found her place in Disney history as Cruella De Vil. It’s a magnificent, flamboyant vocal performance, perfectly in sync with the marvelous character animation of Marc Davis. Davis had found a niche animating women, including Snow White, Cinderella, Tinker Bell, Aurora and Maleficent. Cruella would be Davis’s last major animation work for the studio. Afterwards, he transitioned into the Imagineering division where he worked on pretty much every iconic Disneyland attraction, including Pirates Of The Caribbean, The Haunted Mansion and It’s A Small World. He retired in 1978, was named a Disney Legend in 1989 and passed away in 2000 at the age of 86.

Perhaps the most impressive thing about One Hundred And One Dalmatians is the seeming ease and simplicity of the film. This is one of Disney’s most relaxed animated feature, unfolding at a leisurely but never boring pace. I’ve seen it countless times (this is my girlfriend’s favorite movie, so it’s on heavy rotation here) and it never fails to surprise me how quickly it all breezes past.

It’s a busy movie, making room for all manner of delightful supporting characters including Jasper and Horace, Nanny, the barnyard militia of The Colonel, Sgt. Tibbs and Captain the horse, Old Towser, and the individual puppies, particularly Lucky, Patch and Rolly. The character design is exceptional, down to the smallest walk-on part (including some quick cameos from our old friends from Lady And The Tramp). It even finds time for the genuinely funny TV spoofs What’s My Crime? and The Adventures Of Thunderbolt. And yet for all that, it never feels overstuffed. There is not a wasted moment in the film and not a single scene that overstays its welcome.

The film’s tone is best exemplified by the extraordinary sequence of the puppies being born. As Nanny provides a running tally, Roger and Pongo go through a hilarious mix of emotions, from pride to completely overwhelmed. Then comes the news that one of the puppies didn’t make it. The tone immediately changes. Roger has one idea, gently taking the puppy and massaging its chest. Pongo looks on hopefully, placing a tentative paw on Roger’s knee as the storm rages outside. The music drops out entirely and the action plays out in a single long-shot. It’s magical.

Critics and audiences agreed that Walt had tapped into something special with One Hundred And One Dalmatians. It premiered on January 25, 1961, and raked in over $6 million on its initial release, making it the 8th highest-grossing film of the year. 1961 would be a very good year for Walt Disney. Two of his live-action films did even better. We’ll see the first of those next time.

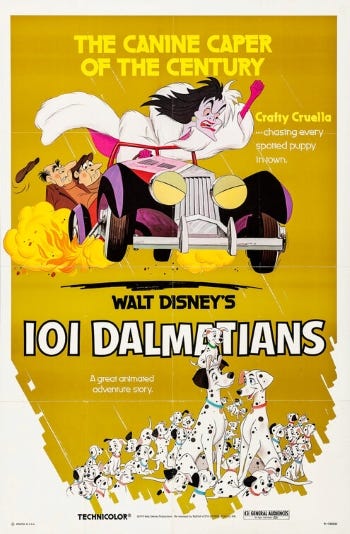

One Hundred And One Dalmatians also become one of those rare films that did even better with each subsequent re-release. In 1969, it made $15 million. The numbers went up again in 1979 and 1985. During its 1991 release, it earned an extraordinary $60 million, making it the 17th highest-grossing film of the year, right behind Kindergarten Cop. By comparison, Beauty And The Beast only made about $7 million more than that.

The dalmatians will, of course, be back in this column. In 1996, Glenn Close helped pioneer the trend of live-action remakes of animated classics with her take on Cruella De Vil in 101 Dalmatians. That film was popular enough to warrant a truly dire sequel, 102 Dalmatians, a short-lived animated series, and a direct-to-video animated sequel to the original, 101 Dalmatians II: Patch’s London Adventure. Waiting in the wings is Cruella, presumably a prequel of sorts with Emma Stone taking on the furs and cigarette holder. That film’s release is currently pending thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic.

One Hundred And One Dalmatians didn’t exactly represent a return to form for Disney animation. It’s too dissimilar from earlier films to be considered a return to anything. And there have unfortunately not been too many movies like it since. Dalmatians is an anomaly, a one-off experiment in loosening the rules that had governed Disney animation for years. The experiment worked. One Hundred And One Dalmatians remains an unqualified success and one of the studio’s very best animated features. But it wasn’t enough to prevent animation from sliding into decline. It’ll be a long time before this column sees another animated feature of this caliber.

VERDICT: Disney Plus