Disney Plus-Or-Minus: One Little Indian

James Garner’s first screen appearance was on the debut episode of the TV western Cheyenne in 1955. By 1973, less than twenty years later, his career had already been a rollercoaster ride. He shot to stardom in 1957 when he landed the lead on Maverick. But his big break came back to bite him just three years later. After a writers’ strike halted production on the series, Warner Bros. put their newest star on suspension. Garner sued the studio for breach of contract and won but, needless to say, wasn’t the most popular guy around Hollywood after that.

After leaving Maverick, Garner transitioned into movies. It took a little while but he eventually broke through as a popular and charming leading man. In 1963, he starred in two very different but equally successful hits: the classic adventure movie The Great Escape with Steve McQueen and the Doris Day rom-com The Thrill Of It All. Once again, James Garner’s career appeared to be back on track.

Wanting to exercise more control over his projects, Garner started his own production company, Cherokee Productions. But his next several projects failed to connect with audiences. When the expensive 1966 racing drama Grand Prix made less money than its studio had hoped, director John Frankenheimer threw Garner under the bus, claiming the movie would have done better if he’d been able to cast his first choice, Garner’s old costar McQueen, or even his second, Robert Redford.

With his movie career moving in fits and starts, Garner went back to television in 1971 with the sorta-western Nichols. Audiences expecting another Maverick were disappointed and the series was canceled after a single season. Shortly after Nichols went off the air, Garner signed a two-picture deal with Disney. This says a lot about both the state of James Garner’s career at the time and the state of Walt Disney Productions.

At the time, A-list movie stars were not lining up to sign contracts with Disney. Garner was by far the biggest name to set up shop at the studio in a long time. But he’d once again become a bigger draw after his Disney contract expired. At the moment, he was a fading leading man in his mid-40s whose best days might have been behind him. Garner lent Disney a bit of credibility at a time when talent was giving the studio a wide berth. In return, Disney gave Garner a gig while he regrouped and figured out his next move.

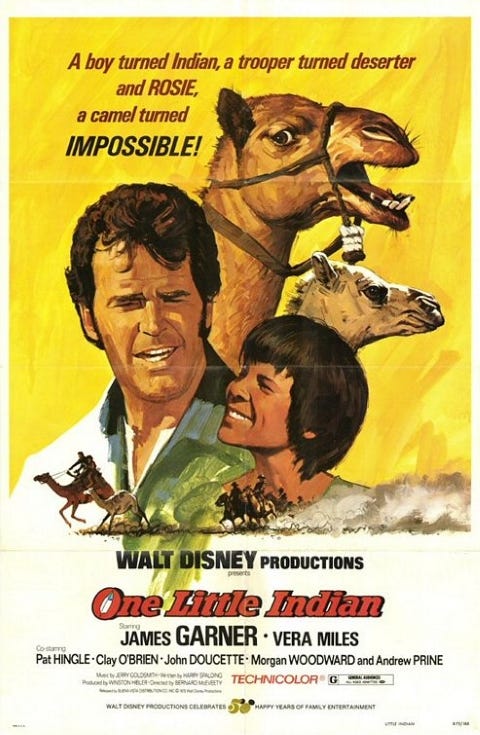

One Little Indian, Garner’s first Disney project, finds the actor squarely in his comfort zone. It’s a western with comedic elements that casts Garner as a possibly roguish but fundamentally decent man of action. True-Life Adventures veteran Winston Hibler produced the film, so if you’re thinking some type of exotic animal will be involved, you’re not wrong. Hibler also brought back Napoleon And Samantha director Bernard McEveety, who had plenty of experience directing episodes of TV westerns.

Unlike a lot of Disney movies, One Little Indian wasn’t based on an existing book or story. The sole credited screenwriter is Harry Spalding. Spalding was a prolific writer of low-budget pictures like Surf Party, Curse Of The Fly and Wild On The Beach. He continued to work for Disney throughout the 1970s and, while most of that was for television, we’ll see him in this column again.

There’s also a new and somewhat surprising name composing the music. Jerry Goldsmith, already a five-time Oscar nominee for his work on such films as Planet Of The Apes and Patton, made his Disney debut on One Little Indian. Disney had a long, long history of relying on its own in-house music department. Seeing Goldsmith’s name pop up so soon after Marvin Hamlisch’s score for The World’s Greatest Athlete makes me suspect the studio was reconsidering the need to keep fulltime songwriters and composers on the payroll.

In One Little Indian, Garner plays Corporal Clint Keyes, a cavalry soldier arrested for desertion. We find out later that he turned against his commanding officer to save the lives of women and children during a raid on an Indian camp. But when we first meet him, he’s handcuffed and riding hellbent for leather across the prairie away from his captors including Sgt. Raines (Morgan Woodward, again reporting for bad guy duty after The Wild Country). Once Raines captures him, he decides Keyes can’t be trusted on horseback, so he forces him to walk, tied to the back of a horse.

After the opening credits, Raines’ party encounters another cavalry unit escorting a ragged band of Cheyenne to the reservation. Raines asks Lieutenant Cummins (the first of several Disney movies for veteran character actor Robert Pine, who you have definitely seen in something if you’ve watched any movies or TV shows over the past few decades) if he can spare an extra man to help with his unruly prisoner. Cummins refuses the request but is pretty sure Raines will meet up with the rest of his unit in a day or two.

Raines rides off with Keyes and the movie decides to follow Cummins and his party back to their fort where Captain Stewart (hey, it’s Pat Hingle!) has been expecting them. Stewart takes stock of his new captives…uh, I mean, guests…and orders the doc to give them a once-over. I probably don’t need to point out that the movie makes zero effort to place any of this business with the Cheyenne into the broader context of the Trail of Tears. These Natives are just part of the background like the mountains and trees.

While the white folks are distracted with the medical exam, a 10-year-old Cheyenne boy sees his chance to escape. He puts up a good fight but is eventually yanked down from a fence, exposing his pale white backside. Yes, it turns out that it’s a white boy, captured by the Cheyenne and raised as one of their own. It’s James MacArthur in The Light In The Forest all over again. I don’t know why Disney decided to go back to this particular well but I’m really hoping this is the last white-child-raised-by-Indians movie I’ll have to sit through. Disney wasn’t equipped to handle this kind of story in 1958 and they still weren’t in 1973.

As in The Light In The Forest, the cavalry is obliged to rip this kid away from the only family he’s ever known and find some well-meaning but misguided stranger to raise him. Here, the fort’s chaplain (Andrew Prine) is that stranger and he’s only too eager to volunteer his services as foster parent. He wastes no time in baptizing the kid and renaming him Mark.

That’s young Clay O’Brien as Mark, by the way. O’Brien made his film debut in the 1972 John Wayne picture The Cowboys. He appeared in a lot of westerns in the 70s, including another one for Disney, before leaving Hollywood to become a cowboy for real. In 1997, he was inducted into the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame. You just never know where these Disney kids are going to end up.

Mark bides his time for a bit and finally manages to sneak away while most of the fort is attending the Christmas Eve service. He sets off in search of his Cheyenne mother, Blue Feather, but the elements take a toll. He’s practically on his last legs when he’s accidentally shot by our old buddy Keyes, who turns out to be a part of this movie after all. He’s had a busy few days himself, escaping from Sgt. Raines and liberating a couple of camels from the military. Really, he just wanted the one but Rosebud (Rosie, for short) wouldn’t leave without her daughter, who Mark names Thirsty.

Keyes douses Mark with carbolic acid and patches him up, offering to travel with him as far as he can before he cuts out to Mexico. A quick stop for a bath reveals Mark’s true identity to Keyes. A couple of points to be made here. First, who decided that showing this kid’s butt was the only way to show he’s not indigenous? Second and more importantly, what difference does it make? It’s not as if the movie has some point it wants to make about Native Americans. It’s like McEveety and Spalding decided the kid had to be an Indian to justify him running into Keyes and he had to be white to justify him speaking English. Neither of those things are true. They’re just lazy.

In any event, Sgt. Raines and his team (which now includes tracker Jimmy Wolf, played by Jay Silverheels, last seen in Smith!) catches up to the pair at the watering hole but Keyes turns the tables on them. His plan does encounter a rather significant hitch. Instead of taking their horses for themselves, they end up scaring them away. But at least their pursuers end up on foot while Keyes and Mark still have their camels.

Next there’s some goofy business with Garner trying to sneak into a cowboys’ camp to steal some food only to have Rosie crash the party and spook the cattle. But the next significant thing to happen story-wise is an encounter with a middle-aged widow (Vera Miles of The Wild Country and a surprisingly large number of other Disney films) and her daughter (Disney appearance #2 for Jodie Foster). Doris McIver recently lost her husband and she plans on taking young Martha back to Colorado in just a few days. That suits Keyes fine, since he just wants to rest up, shave and maybe scrounge a hot meal or two for himself and Mark.

Martha is delighted by the camels and tries her best to befriend Mark, while Doris is delighted by Keyes, especially after he shaves. Keyes explains their situation to the widow and confesses that he really doesn’t know what to do with Mark. He can’t bring him to Mexico but he also can’t escort him back to the reservation without putting his own neck in a noose. Doris sympathizes with the fugitives and can’t ignore the spark between her and Keyes, so after thinking it over for all of thirty seconds, she agrees to bring Mark to Colorado with them. Mr. McIver must have been a real catch for his wife to agree to adopt a kid who thinks he’s an Indian on the off-chance it might eventually help her land a new man.

Satisfied that Mark’s in good hands, Keyes sneaks off in the middle of the night. The next morning, Mark is understandably upset. But he can’t pout for long because that mean old Sgt. Raines requisitioned some new horses off the cowboys Keyes tried to steal from earlier and he shows up demanding satisfaction. Mark runs away and soon, both he and Raines are tracking Keyes. As for Doris and Martha, they pack up and head for Colorado as scheduled. This might be the only normal human behavior depicted in the entire film.

Mark turns out to be a better tracker than Raines and Jimmy Wolf. Keyes had grabbed his gear and sent Rosie off alone, so while the bad guys were following a riderless camel, Mark picks up the scent of carbolic acid and catches up to Keyes. Mark is plenty pissed off and Keyes’ explanation that Blue Feather and the rest of the Cheyenne would reject Mark even if he could find them doesn’t help. The dynamic duo is about to split up again when Raines finally shows up. Mark escapes with the camels but Keyes is captured and taken to the nearest cavalry outpost, which happens to be the same one Mark escaped from, which means the chaplain absolutely could have found Mark if he’d put any effort into it.

Captain Stewart returns to the fort and is not amused by the freshly constructed gallows in his courtyard. He demands to see both Raines and Keyes and wastes no time in sizing up Raines as an enormous asshole. Still, orders are orders. Stewart allows Raines to continue with the hanging with the understanding that none of his men will have anything to do with it and Raines had better be on his way the second the deed is done.

As his last request, Keyes asks the chaplain to find Mark and see him safely brought to the McIvers in Colorado. The chaplain agrees, probably just relieved to be off the hook from his impulsive decision to adopt the kid himself, and escorts Keyes to the gallows. Raines slips the noose around Keyes’ neck and is ready to drop him when Mark and Rosie come to the rescue. Keyes drops but the scaffold is destroyed before he’s hung. In the ensuing melee, Keyes is able to escape with Rosie but Mark is recaptured.

Raines takes off in hot pursuit but eventually is forced back to the fort for reinforcements. However, Captain Stewart informs him that the case is officially closed. Raines’ orders were to hang Keyes and Keyes has now been hung. Whether or not he died is irrelevant. Stewart’s not going to hang a man for the same crime twice. The chaplain rides out to let Keyes know he’s a free man and deliver Mark. Sadly, Rosie was fatally wounded in the getaway. After a proper funeral, Keyes, Mark and Thirsty saddle up and head north for what they hope will be a happy reunion in Colorado.

In his memoir The Garner Files, James Garner is pretty harsh on One Little Indian. “I’ve done some things I’m not proud of,” he writes. “This is one of them.” Part of me wants to push back against that sentiment and say it’s not that bad. But I appreciate Garner’s candor and far be it from me to disagree with someone who always seemed to possess a healthy and accurate degree of self-evaluation. He’s right. One Little Indian sucks.

In its meager defense, Garner himself is always a pleasure to watch. I’m not going to say he’s doing his best because I don’t think he was and frankly, the material didn’t deserve his best. Even so, you can’t help but like him no matter how weak the movie. James Garner made Polaroid commercials fun to watch. Of course he elevates this.

The same is true of Pat Hingle, who gets probably the most purely satisfying scene in the movie when he chews out Sgt. Raines. And it’s still fun watching Jodie Foster grow up on screen. In the year between this and Napoleon And Samantha, she’d had a smallish role in the Raquel Welch roller derby movie Kansas City Bomber, starred as Becky Thatcher opposite Johnny Whitaker in the Sherman Brothers non-Disney musical Tom Sawyer, and done a bunch of live-action and animated TV work. One Little Indian would be her last Disney movie for a little while. The next time we see her in this column, her career will be in a very different place.

Unfortunately, everything else about One Little Indian is bottom-of-the-barrel Disney at its worst. The comedic hijinks of the camels aren’t that funny and they’re shoehorned in between mawkish melodrama about Mark’s quest for a real family. As in The Light In The Forest, McEveety and Spalding are either unwilling or unable to admit that Mark’s family was the Cheyenne who raised him. But James MacArthur’s character in The Light In The Forest was older than Mark, so that movie was a bit more interesting in its depiction of the tension between his two sides. Mark’s ten years old. As far as we know, he doesn’t remember his birth parents at all. So if you’re not prepared to address his relationship with the Cheyenne, and Spalding and McEveety most definitely are not, you’re just not engaging with this material in any meaningful way.

Mark doesn’t display much personality at all. He keeps saying he wants to get back to Blue Feather but he doesn’t show it. And we get absolutely no indication what Blue Feather thinks about him. So it’s really difficult to care what happens to this kid, even after the chaplain, Keyes, Doris, Martha and half the camp go on about how much they want to help him. I feel worse for the camels than I do for Mark.

At the end of the day, James Garner wasn’t the only one who didn’t care for One Little Indian. The movie was released June 20, 1973. It ended up making about $2 million which, even in 1973, was not a lot. It came and went quickly, leaving barely a ripple to mark its passing. And yet, Garner still owed the studio another picture. Something tells me he hoped to knock it out and get it over with as quickly as possible.

VERDICT: Disney Minus

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!