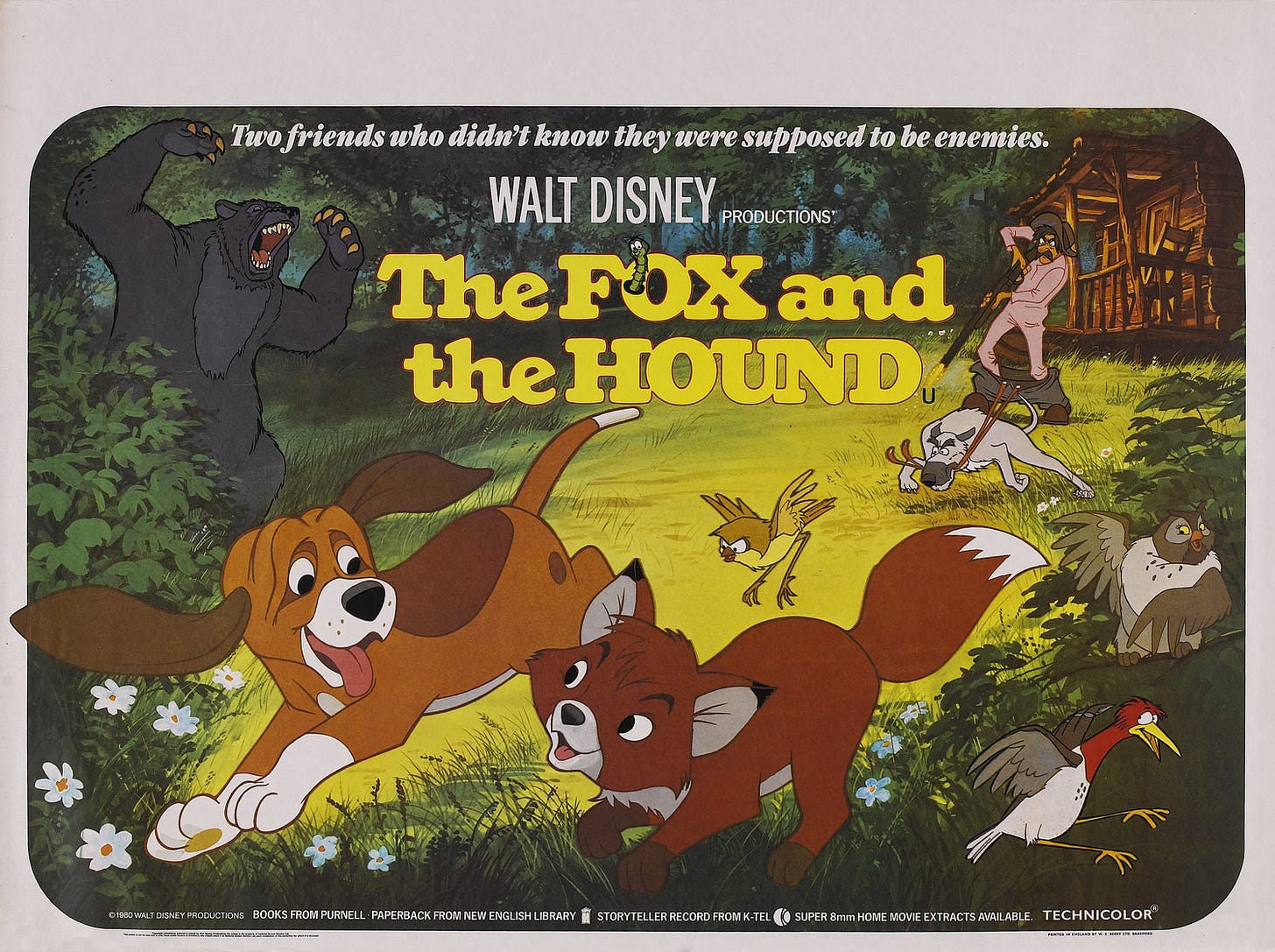

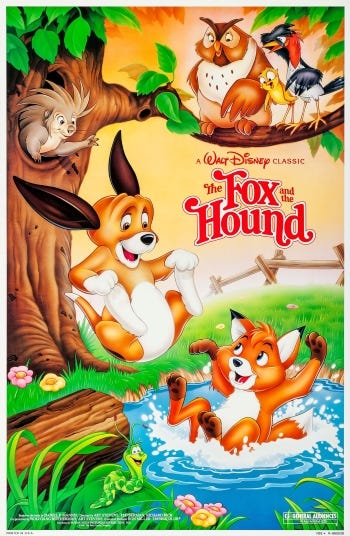

Disney Plus-Or-Minus: The Fox And The Hound

For as much as Disney was struggling in the late ‘70s (and would continue to well into the ‘80s), animation remained a reliable source of both income and good will. Their last animated feature, The Rescuers, had been a sizable hit with audiences and critics in 1977, helping the studio weather the onslaught of Star Wars. But unbeknownst to many people, a changing of the guard was taking place behind the scenes and it was not going well.

The Fox And The Hound was originally scheduled to be Disney’s big Christmas release for 1980. But midway through production, rising star Don Bluth dramatically quit, leading an exodus of talented animators to his own independent studio, Don Bluth Productions. As a result, The Fox And The Hound was delayed by six months, pushed back to the summer of 1981.

To get to the root of the conflict, we need to go back to the project’s origin in 1967. That’s when author Daniel P. Mannix published his novel, The Fox And The Hound. Mannix was an interesting character in his own right, having worked as a sideshow performer, a stage magician, a professional hunter and a photojournalist. Mannix wrote a lot, both fiction and nonfiction, on such diverse topics as a history of sideshow freaks, a biography of occult guru Aleister Crowley, and a historical novel about the Roman games called Those About To Die, an alleged inspiration for Ridley Scott’s Gladiator. You probably didn’t expect there to be a line connecting The Fox And The Hound to Gladiator but here we are.

Prior to its publication, Mannix’s book won the Dutton Animal Book Award recognizing outstanding writing about animals. Previous winners had included Sterling North’s Rascal (made into a live-action Disney movie in 1969) and Walt Morey’s Gentle Ben. So it makes sense that Disney bought the rights to The Fox And The Hound as soon as Mannix’s book won the Dutton prize. Once they had it, they proceeded to do absolutely nothing with it for the next decade. They didn’t know what they wanted to do with the book. They just knew they didn’t want anybody else to have it, either.

Work on the film didn’t begin until 1977 when Wolfgang Reitherman, looking around for a follow-up to The Rescuers, read the book. One of his kids had evidently kept a pet fox for a time and Reitherman thought the story had potential. This despite the fact that Mannix’s novel is absolutely not a kids’ book. Granted, Disney has never been shy about altering source material to suit their needs and we’ll get into some of the changes that were made later. Suffice to say that this was never going to be an easy project to adapt.

Woolie Reitherman began developing the project with Art Stevens, a longtime Disney animator who had finally been bumped up to co-director on The Rescuers. Stevens was slightly younger than Reitherman, having joined the studio as an in-betweener on Fantasia, and not officially a part of the legendary “Nine Old Men” who’d been there practically since the beginning.

Stevens ended up being sort of a middleman between Reitherman and the younger animators led by Don Bluth, who was likely next in line to move up the ranks and co-direct. Bluth had distinguished himself on The Rescuers and Pete’s Dragon and had recently directed a short film, The Small One. Bluth and Reitherman did not get along and argued on a number of story points.

Bluth won a few of those fights. For example, Woolie felt the second act needed punching up and wanted to include a song called “Scoobie-Doobie Doobie-Doo, Let Your Body Turn To Goo”, a duet between The Jungle Book’s Phil Harris and Latin “cuchi-cuchi” girl Charo, of all people. Even Stevens agreed this was a bad idea. The song did not survive the development process.

But a bigger point of contention revolved around the incident that drives a wedge between childhood pals Tod (the fox) and Copper (the hound). When Tod goes to visit Copper after they return from hunting season, Tod is chased away by Copper’s master, Amos Slade, and his mentor, the older dog, Chief. Copper tries to let Tod go but Chief chases him onto a railroad bridge where he’s struck by a train. Bluth and the younger animators wanted Chief to die, as he does in the original book. They argued the story made no sense if Chief survived with just a broken leg.

Reitherman and Stevens weren’t having it. As far as Woolie was concerned, a Disney movie would never kill a character like that (guess it’d been awhile since he’d seen Bambi). In the end, the old guard won and Chief lived. But Bluth had had enough. In 1979, with the film well into production, Bluth quit, with 15 more animators following him. A few years later, Bluth’s new animation studio would release The Secret Of NIMH, posing a direct challenge to Disney’s animation dominance.

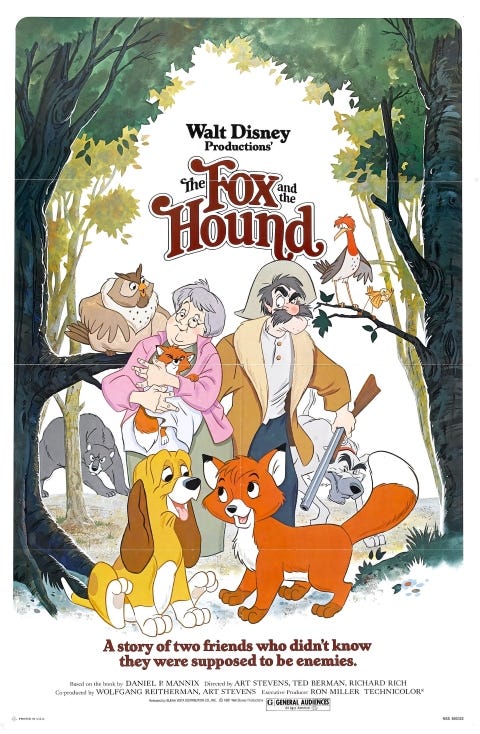

Woolie may have won the battle over Chief but he ended up losing the war. Between the inappropriate song and the mass defection of animators, executive producer Ron Miller began to suspect Reitherman was not the right fit. He ordered Reitherman to hand over the reins. Art Stevens would co-direct with Ted Berman, an animator and story-man who had been with the studio since the 1940s, and Richard Rich, whose first screen credit had been on Winnie The Pooh And Tigger Too in 1974.

This was close to the last straw for Reitherman. He continued to develop a few more projects, none of which came to fruition, before retiring in 1980. On May 22, 1985, Wolfgang Reitherman died in a car accident. He was 75 years old. In 1989, he was posthumously and very deservedly inducted into the very first group of Disney Legends alongside his fellow Nine Old Men.

Caught up in the behind-the-scenes turmoil was a group of young animators, most of whom were graduates of CalArts’ animation program who had moved into Disney’s own in-house training ground. Today, the list of names is a who’s who of animation A-listers: Tim Burton, Brad Bird, John Lasseter, John Musker, Ron Clements, Glen Keane, Henry Selick and others got their start on The Fox And The Hound.

There were also plenty of familiar names in the vocal cast. Mickey Rooney, who had recently made his Disney debut in Pete’s Dragon, voices Tod. Then pushing 60, the Mickster may not seem like an obvious choice to play a scrappy young fox but there’s no trace of advanced age in his voice. Former Disney superstar Kurt Russell returned to the studio for the first time since The Strongest Man In The World to play Tod’s best friend, Copper. Russell was leaving his child star days behind, playing the title role in John Carpenter’s Elvis when he recorded his dialogue for The Fox And The Hound. To date, it remains his only vocal performance in an animated feature.

We’ve heard and/or seen most of the animals in The Fox And The Hound many times. Tod’s love interest, Vixey, is Sandy Duncan, last seen in The Cat From Outer Space. Dinky and Boomer, the birds who help rescue Tod, are frequent bit player Dick Bakalyan (most recently in Return From Witch Mountain) and Paul Winchell, instantly recognizable as Tigger. Piglet’s here too, as John Fiedler pops up as a friendly porcupine. And Pat Buttram finds a more geographically appropriate place for his voice than The Aristocats or Robin Hood as Chief, the not-as-ill-fated-as-he-could-have-been hunting dog.

New to the Disney operation was Pearl Bailey, the great singer and stage performer, who voiced the maternal owl, Big Mama. The studio also found two newcomers to play the younger versions of Tod and Copper. Keith Coogan (then billed as Keith Mitchell) was the grandson of Jackie Coogan, one of the film industry’s first big child stars. Keith will be back in this column eventually. Corey Feldman, on the other hand, will not. He went on to become one of the most ubiquitous child/teen stars of the 1980s, appearing in movies like Gremlins, Stand By Me, and Dream A Little Dream, without returning to Disney before going on to become…well, Corey Feldman.

The film’s two human characters also had previous Disney experience. Widow Tweed was voiced by Jeanette Nolan, another alumnus from The Rescuers. Jack Albertson, the voice of Amos Slade, was new to voice work but he’d appeared in live-action films like Son Of Flubber and A Tiger Walks. The Fox And The Hound would be his final film before his death on November 25, 1981, at the age of 74.

The humans are just two examples of where the film departs from Mannix’s book. The Widow was a completely new invention while Amos, referred to only as “The Master” in the novel, has a considerably different arc. The book spans several years while the movie condenses the story down to right around a single year. And in the book, Tod and Copper are never friends. Not even close.

In the book, Tod is raised by one of the hunters who kills his mom instead of the Widow. That incident is depicted in the film’s opening sequence, for those who felt that Bambi waited too long to get to the really traumatic material. Tod is then released back into the wild fairly early on in Mannix’s book. He trains himself to survive in the wild by outsmarting the Master’s dogs, led by Copper and Chief.

Copper is the older dog in the original, somewhat resentful of Chief’s enthusiasm and skill. Switching their ages at least makes some sense. Chief definitely sounds like the name of an older, more experienced dog. Chief’s enthusiasm gets the better of him when he tears off after Tod. As in the film, the chase culminates on a railroad trestle. But Mannix has Tod deliberately jump out of the way at the last minute, killing Chief and inspiring the Master to train Copper to avenge his death. Granted, Mannix avoids anthropomorphism and depicts the animals as simply following instinct. Still, it’s rough stuff.

Years go by and Copper and the Master try time and time again to get Tod. Tod takes a mate and they have a litter of kits. The Master tracks them to their burrow and gasses Vixey and her kids to death. Tod mourns them, eventually finds another mate and the Master kills her, too!

While the Master is racking up a body count, the city is encroaching on his land. Between the city trying to push him out and his obsession with Tod, the Master develops a severe drinking problem. Eventually, an outbreak of rabies leads people to ask the Master and Copper to help drive out the fox population. Copper catches Tod’s scent and pursues him relentlessly through the woods until finally, Tod drops dead of exhaustion. Copper collapses on top of him and the Master brings him home.

But that’s still not quite the end of this descent into primal despair! The old drunk Master ends up losing his land and is forced to move into an old folks home. Guess what? The assisted living facility doesn’t allow dogs. So, the Master takes his old faithful hunting dog, Copper, and shoots him in the head. Bam. The end. I swear I’m not making any of this up. Hard to imagine “Best Of Friends” playing over the end credits of that version, huh?

Obviously, there’s no world where Disney was ever going to make a faithful animated adaptation of that story. It combines all of the most deeply upsetting elements of Bambi and Old Yeller with virtually none of the uplift. Reframing the book so that Copper and Tod are childhood pals who are forced by training to become enemies is a good idea that turns the story into more of an allegory than Mannix may have intended. But even by that metric, Disney’s movie is a lot sadder than you may remember.

The question remains over whether or not Chief should have been allowed to die. The younger animators were correct in that Copper’s motivation isn’t really there, especially since Chief is depicted as milking his broken leg for all its worth. But killing the dog would have been grim stuff for a Disney movie and I’m not sure if they could have pulled that off or not.

Bear in mind that animation matured rapidly in the 1970s. Just a few years prior to the release of The Fox And The Hound, Martin Rosen’s adaptation of Richard Adams’ novel Watership Down was released to theaters. Some may argue that Watership Down wasn’t really geared toward younger audiences. As a 9-year-old whose mother took him to see Watership Down in 1978, I can attest to the fact that it very much was presented that way, whether Rosen intended it to be or not. I certainly don’t remember being traumatized by the film. If anything, I thought it was a little boring and slow. (I was 9. I’ve revised my opinion since then.)

No one would argue that Disney didn’t have the expertise to craft a film on the level of Watership Down. From a purely technical perspective, they could have easily surpassed it. But the friction between the younger animators who desperately wanted to try something new and the older generation clinging to the tried-and-true Disney formula would have never allowed it. It is a little disappointing that the new guard never even got a chance to try.

Many of the elements in The Fox And The Hound that don’t quite work are remnants of the Disney house style. The character design is a little too familiar and cartoony. The songs, by Stan Fidel, Jeffrey Patch and country star Jim Stafford, are either unnecessary or tug a little too hard on the heartstrings. And it’s a little too obvious that the supporting characters are only around to provide comic relief. You could pluck Dinky and Boomer’s entire subplot revolving around their pursuit of Squeaks the caterpillar out of the movie entirely and it wouldn’t hurt a single thing.

But Disney deserves a lot of credit for the things that do work and most of the film does. The opening title sequence is a stark departure for the studio, slowly moving through the forest with no music, just a slow crescendo of ambient sound. The Fox And The Hound is frequently remembered as being one of Disney’s corniest, even saccharine films. But Stevens, Berman and Rich are not afraid of embracing the story’s darkness. The sequence on the trestle and a climactic bear attack feature some of Disney’s most intense animation.

The relationship between Tod and Copper is genuinely affecting thanks to the lovely character animation and warm, sincere vocal work by Coogan, Feldman, Rooney and Russell. And the movie’s final shot, with Tod and Vixey standing apart on a hill overlooking Copper at home, might be the most bittersweet moment in Disney animation. I imagine a lot of parents have had to have very complicated conversations with their kids after that.

The Fox And The Hound was finally released on July 10, 1981, the same day as a very different Kurt Russell movie, John Carpenter’s Escape From New York. Disappointingly, a lot of critics dismissed it as more of the same old Disney hokum. Only a handful, including Roger Ebert and Richard Corliss, saw what the studio was trying to accomplish and praised the film for attempting something different.

Audiences didn’t exactly flock to The Fox And The Hound. The studio was still several years away from releasing an animated feature that would be considered a must-see event. But it did well enough with families to become a respectable hit and Disney’s highest-grossing release of 1981, landing a bit outside of the year’s top ten between Warren Beatty’s Reds and Bo Derek’s Tarzan The Ape Man (talk about strange bedfellows).

In 2006, Tod and Copper returned in the direct-to-video The Fox And The Hound 2, a sort-of sideways sequel that takes place sometime in the middle of the first film. It had a slightly higher pedigree than some of Disney’s DTV sequels with voices by Reba McEntire and Patrick Swayze. The movie was received reasonably well (again, especially in comparison to other direct-to-video fare) but Disney hasn’t continued to exploit the Fox-And-The-Hound-iverse.

Today, The Fox And The Hound shows Disney at a crossroads. It’s a transitional film between the classics produced by Walt’s original animators and the new classics to come from their proteges. As such, it’s hardly surprising that the movie isn’t entirely successful. But it’s a better film than I remembered and a mini-milestone for its passing-of-the-torch qualities alone. It’s a welcome reminder that change never happens quickly or easily and not every turning point is marked with sound and fury.

VERDICT: Disney Plus

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!