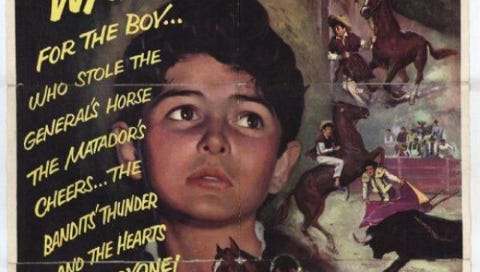

Disney Plus-Or-Minus: The Littlest Outlaw

The Littlest Outlaw is a minor entry in the Disney canon. It’s rarely allowed out of the Disney Vault. The studio released it on VHS back in 1987 and as a Disney Movie Club Exclusive DVD in 2011. It has not been released on Blu-ray and isn’t currently available on Disney+, although a high-def version is available to rent or buy digitally on platforms like Vudu and iTunes. And while I’m not going to make the case that this is some kind of neglected masterpiece, The Littlest Outlaw is a better movie than its low profile would suggest.

The movie was the brainchild of producer Larry Lansburgh. Lansburgh started out as a stuntman before a fall from a horse broke his leg and ended his on-camera career. In 1938, he took an entry-level job at Disney, eventually making his way into editing. In 1941, he was part of El Grupo, the South American goodwill tour of Disney artists sponsored by the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs. Lansburgh shot some of the 16mm footage that later appeared in Saludos Amigos and was an associate producer on The Three Caballeros.

Throughout his career, Lansburgh’s first love remained animals, horses in particular. In 1954, he produced and directed Stormy, The Thoroughbred, a 45-minute featurette about a racehorse who’s bought by a champion polo player. Lansburgh next pitched Walt the idea for The Littlest Outlaw. Walt, who was also an avid polo player and horse-lover himself, liked the idea.

With Lansburgh producing, Walt gave the story to Bill Walsh to flesh out into a screenplay. Walsh had started out writing various Disney comic strips like Mickey Mouse and Uncle Remus. Recently, he’d been put in charge of television, producing major hits like Davy Crockett and The Adventures Of Spin And Marty. The Littlest Outlaw would be his first feature film but it was far from his last. We’ll see plenty more of Bill Walsh’s work in this column.

Lansburgh’s south-of-the-border trip evidently made quite an impact on him. There’s no real reason why Lansburgh couldn’t have simply hired a local crew, driven half an hour in any direction from the Burbank studio and made The Littlest Outlaw there. But Lansburgh wanted his film to have authenticity. To direct, he hired Roberto Gavaldón, one of Mexico’s leading filmmakers. The film was shot entirely on location in Mexico by a bilingual cast and crew.

Contemporary critics are all too eager to condemn movies of the past for whitewashing or indulging in outdated and offensive cultural stereotypes. So it’s disappointing when a movie like this gets it right and doesn’t receive the credit it deserves. Representation does matter and Disney and Lansburgh deserve to be acknowledged for engaging so many Hispanic artists in front of and behind the cameras.

In fact, Gavaldón actually shot the movie twice, once in English and again in Spanish. The Spanish version, El pequeño proscrito, makes a few changes. Most notably, Mexican actor and singer Pedro Vargas appears as Padre, a role played by Joseph Calleia in the English-language version. This version is difficult if not downright impossible to see these days, which is too bad. I’d love to see how the Spanish version differs from the English.

The movie itself is a pleasant if unsurprising story of friendship between a boy, Pablito (Andrés Velázquez), and a horse. The horse, Conquistador, is owned by General Torres (played by John Ford regular Pedro Armendáriz). Torres plans on riding Conquistador to victory in an upcoming show but the horse refuses to make the high jump. Pablito’s stepfather is the horse’s trainer but his abusive methods only make the horse even more afraid to jump. When Conquistador’s skittishness causes the General’s young daughter to be thrown off, Torres orders the animal killed. But Pablito knows it isn’t Conquistador’s fault, so he runs away with the horse, encountering outlaws, gypsies and a kind-hearted priest (Calleia).

Again, none of this is exactly groundbreaking. You’ve seen variations of this story before. Unfortunately, the weakest link is young Velázquez, who seems stiff and uncomfortable throughout. Maybe he gives a more relaxed, natural performance in the Spanish-language version. The grownups, on the other hand, are a lot of fun, especially Calleia as the Padre. Calleia enjoyed a long Hollywood career, often playing bad guys and dark, shadowy figures. The Littlest Outlaw is the opposite of that. Calleia seems to be having a good time as the friendly, easy-going Padre who offers sanctuary to Pablito and Conquistador.

While the locations are lovely and the performances are generally solid, the film could use a little more Mexican flavor to spice things up. It makes a move in the right direction in its final act as Pablito’s journey takes him into the bullfighting arena where he encounters legendary matador Pepe Ortiz, played by none other than Pepe Ortiz himself. We get to see some authentic bullfighting action and while it isn’t as graphic or violent as some I’ve seen, it’s still plenty real. Bullfighting has become a controversial sport in the West, especially among animal rights activists. It could be this aspect of the film that prevents Disney from making it more readily available. None of the footage is particularly disturbing, unless you’re simply against the very idea of bullfighting at all. But Disney tends to react (or overreact) on the side of caution when it comes to potentially touchy subjects.

The Littlest Outlaw was Disney’s Christmas release for 1955, a big year for Walt in virtually every respect. His television presence was firmly established thanks to both the weekly Disneyland anthology series and the daily Mickey Mouse Club. Disneyland, the theme park, opened in July and after a fairly disastrous opening day, was rapidly turning into one of Southern California’s must-see attractions. And at the movies, Lady And The Tramp had become Walt’s biggest animated hit in years, while the first theatrical compilation of Davy Crockett episodes was essentially a license to print money.

But The Littlest Outlaw ended 1955 with a bit of a whimper. Critics dismissed it and, after its original theatrical release, it didn’t leave much of a cultural footprint. The studio did release a record, The Story Of The Littlest Outlaw, narrated by Jiminy Cricket for whatever reason. The record stayed in print well into the 1960s, periodically getting re-released alongside other stories like Bongo and The Three Little Pigs. It seems possible that more kids ended up becoming familiar with Jiminy Cricket’s telling of the story than the original film.

There’s no real reason for Disney to keep The Littlest Outlaw under wraps. It’s a fine little movie. Nothing you haven’t seen before but it’s a perfectly agreeable rainy afternoon movie. They’ve certainly shined a spotlight on far worse. Ideally, they should release both the English and Spanish-language versions on Disney+. They could use more multilingual programming and it would be fascinating to compare the two versions. Honestly, a Disney en español collection would be a nice addition to the service. Give me a call, Disney+ Folks! I’m available for consulting both on a freelance or a more permanent basis.

VERDICT: Not quite a Disney Plus but better than a Disney Minus, so I guess that makes it just Plain Disney.