Disney Plus-Or-Minus: The Living Desert

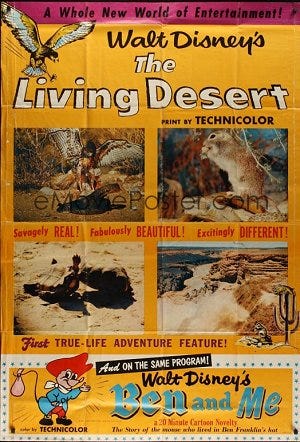

The Living Desert may appear to be a minor entry in the Disney catalog. It isn’t a cartoon, although it does open with a few minutes of animation. It’s live-action but there isn’t a single human being to be seen. But this feature-length nature documentary represents a significant milestone for the studio. To see why, we’ll eventually have to go all the way back to Disney’s very first films. But first, let’s rewind just a decade or so.

Walt Disney first got into documentary filmmaking during the war years, producing the feature-length Victory Through Air Power and assorted short subjects to help with the war effort. This opened up a little side business producing educational shorts for corporate clients like General Motors and Johnson & Johnson. These projects kept the studio afloat during the lean years of the 1940s.

An inveterate traveler throughout his life, Walt made his first trip to Alaska in 1947. He fell in love with the area and was eager to see more. A friend suggested he check out the work of Alfred and Elma Milotte, a husband-and-wife team of nature photographers. Walt was impressed with their work and commissioned them to return to Alaska and film whatever they wanted. He didn’t particularly know what he was going to do with the footage. He just wanted to see what they’d get.

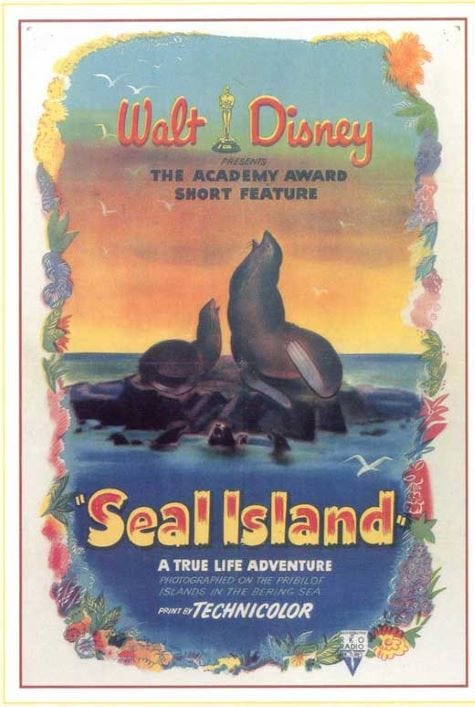

The Milottes shot thousands of feet of film. Out of all this, Walt was most interested in footage they’d captured of seals cavorting on the Pribilof Islands. He assigned James Algar, an animator who had directed The Sorcerer’s Apprentice segment in Fantasia and Victory Through Air Power, the job of building a narrative around the footage. The resulting half-hour short, Seal Island, was presented as the first in a series of films called True-Life Adventures.

Both Walt and Roy Disney felt that Seal Island was a winner. But RKO, their distributor for over a decade, didn’t want anything to do with it. Only after Seal Island won the Oscar for Best Live Action Short Subject did they agree to put it in theatres.

Over the next few years, Disney, Algar, the Milottes, writer/narrator Winston Hibler and producer Ben Sharpsteen made half a dozen more True-Life Adventures. Four of them, In Beaver Valley, Nature’s Half Acre, Water Birds, and Bear Country, won Academy Awards. The series was an unqualified success. As far as the Disneys were concerned, a full-length feature seemed like the next logical step.

The Living Desert was inspired by the work of photographers N. Paul Kenworthy, Jr. and Robert Crandall. Kenworthy was a graduate student working on a short film for his thesis project. He’d made some amateur 8mm films of insects and had read about Pepsis wasps, a large desert insect that preys on tarantulas. Nobody had ever filmed a wasp/tarantula battle before, so Kenworthy contacted Crandall, an entomologist based out of Arizona. Crandall’s scientific knowledge and Kenworthy’s skill with the camera allowed them to capture the entire event on film.

Kenworthy brought his footage to Disney, thinking it might make for a good True-Life Adventure. Walt loved it, bought the footage immediately and hired Kenworthy and Crandall to head back to the desert to get more. This also meant that Kenworthy had to start over on his thesis project, since he’d sold the rights to his film, but it seemed to work out all right for him.

The Living Desert was ready for release in 1953. But this time, RKO flat-out refused to distribute it. They had begrudgingly released the other True-Life Adventures shorts but a feature-length documentary was not what they wanted from Disney. This would be the last straw in the long-simmering feud between Disney and RKO.

Walt and Roy had struggled with their distributors from the very beginning. Their relationship with their first distributor, Margaret Winkler, fell apart when she stepped away from the busines and put her husband, Charles Mintz, in charge. Walt created Oswald the Lucky Rabbit for Mintz. When the character became popular and Walt pressed for a better deal, Mintz went behind his back and hired virtually his entire staff away from him. Mintz also kept the rights to Oswald, inspiring Walt and Ub Iwerks, the only animator who remained loyal to him, to create a new character, Mickey Mouse.

Walt didn’t have much better luck with his next distributor, Pat Powers. Disney had originally signed with Powers to use his Cinephone recording system while making Steamboat Willie. But the terms of the arrangement were heavily in Powers’ favor. Once again, Walt tried to negotiate a better deal only to have Powers poach his key men. This time, he even lost Ub Iwerks, as well as composer Carl Stalling. As a result of the strain, Walt suffered a nervous breakdown in 1931.

Once he was able to extricate himself from the Powers deal, Walt signed up with Columbia to distribute the Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphonies cartoons. That relationship soured in 1932 when Walt moved over to United Artists. By 1937, UA was pressuring Walt to sign over the television rights to his cartoons. TV was still very much in its infancy and Walt, having been burned repeatedly in the past, wasn’t about to commit to a long-term contract for something that wasn’t yet fully understood. So Walt left the studio and signed up with RKO.

The relationship between RKO and Disney had its ups and downs. RKO had been reluctant to release some of Disney’s earlier films, including Dumbo (too short), Fantasia (too arty) and Victory Through Air Power (which they also turned down entirely, leading Walt to release it through UA). For their part, Roy and Walt had been unhappy with RKO’s lackluster promotional efforts.

In 1948, multimillionaire and movie dabbler Howard Hughes took control of RKO. Hughes proceeded to run the studio into the ground, releasing a mix of expensive flops and low-budget B-movies. During these years, Disney provided some of the few hits RKO had. At one point, Hughes even offered to sell RKO to Disney. Walt passed, supposedly saying something like, “I already have a movie studio. What would I want with another?” I can honestly not imagine any of Disney's current executives expressing this sentiment.

By 1953, Disney was doing more for RKO than RKO was doing for Disney. After giving the studio a string of huge hits like Treasure Island and Peter Pan, Walt and Roy felt they’d earned the right to release whatever they saw fit. When RKO passed on The Living Desert, they decided they’d had enough of outside distributors. Roy proposed creating their own distribution arm. Walt liked the idea but didn’t want to be too involved, busy as he was with plans for Disneyland and his TV show. So Roy ran point on the new venture and established the Buena Vista Film Distribution Company, named after the Burbank street where the studio stood.

The Living Desert was the first Buena Vista release and it was an immediate success. It raked in millions at the box office, both domestically and internationally, and had only cost about $300,000 to make. Buena Vista was off to a very profitable start.

Watching The Living Desert (or indeed any of the True-Life Adventures) today, it’s immediately apparent that this is the work of animators, not seasoned documentarians. Winston Hibler, who cowrote the scripts with James Algar and provided the narration, had been a story man. Beginning with the Johnny Appleseed segment in Melody Time, he contributed to The Adventures Of Ichabod And Mr. Toad, Peter Pan and several other animated features. Algar had been with Disney since Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs.

Algar and Hibler imbue the animals in The Living Desert with distinct personalities, giving them names like Skinny and Mugsy. That isn’t too difficult when you’re showing a bobcat get chased up a cactus by a pack of wild boars. But it’s quite another thing to anthropomorphize more alien-looking creatures like wasps and scorpions.

The biggest weapon in their arsenal is the omnipresent use of Paul L. Smith’s music. Disney pioneered the use of music in animation and that influence extended over into live-action films. So much so that the technique of exactly synchronizing music to the action on-screen is referred to as “Mickey Mousing”. In general, that term is not considered complimentary.

The Living Desert is guiltier of Mickey Mousing than most actual Mickey Mouse cartoons. When a couple of cute baby coatis (kind of a desert cousin to the raccoon) fall asleep in their nest, you can be sure that Smith will cue up “Home Sweet Home”. The most extreme example is the mating dance of the scorpions, which Smith and Hibler turn into a full-on country jambaroo complete with square dancing calls and manipulated footage to make it look like a nearby owl is also getting down.

Critics and naturalists cried fowl at obviously staged sequences like this but audiences at the time certainly didn’t mind. They also shouldn't have been surprised. Walt had already proven that he wasn't above creating an entirely fictional narrative to get across some broad facts in the studio tour feature The Reluctant Dragon. At least he didn't try to make it look like Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy were on a desert safari.

Despite the somewhat dubious educational value of such tricks, The Living Desert went on to win the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. It was a big night for Disney. Even though none of his animated or live-action features were even nominated that year, Walt cleaned up in other categories. Bear Country won Best Live-Action Short Subject (Two-Reel). The Alaskan Eskimo, the first entry in a sister series to True-Life Adventures called People & Places, won Best Documentary Short Subject. And the great Toot, Whistle, Plunk And Boom won Best Short Subject (Cartoons). The four Oscars Walt won set a record for the most taken home by an individual in a single night.

The Living Desert has had a much longer shelf life than most documentaries from the 1950s. It was re-released theatrically a few times over the years. I remember watching it and other True-Life Adventures in school, a good 25 years after its original release. Today, it’s available on Disney+ and I can vouch for the fact that kids are still watching these vintage True-Life Adventures. Just this past July, we went to visit my girlfriend’s family. Her young nephews cycled through at least three of them one afternoon and, near as I could tell, that was all their idea.

By treating nature like a cartoon, Walt found a way to give documentaries a timeless appeal. The studio continues the tradition today with the Disneynature films. Celebrity narrators have replaced the friendly, folksy voice of Winston Hibler and sometimes they get an IMAX upgrade. But the spirit of the True-Life Adventures lives on. We will see more of them in the weeks ahead.

VERDICT: This is one of the few films I’ve ever watched that completely captivated my cat. Any movie that can hold a cat’s attention for over an hour has to be considered a Disney Plus.