Disney Plus-Or-Minus: The Sword And The Rose

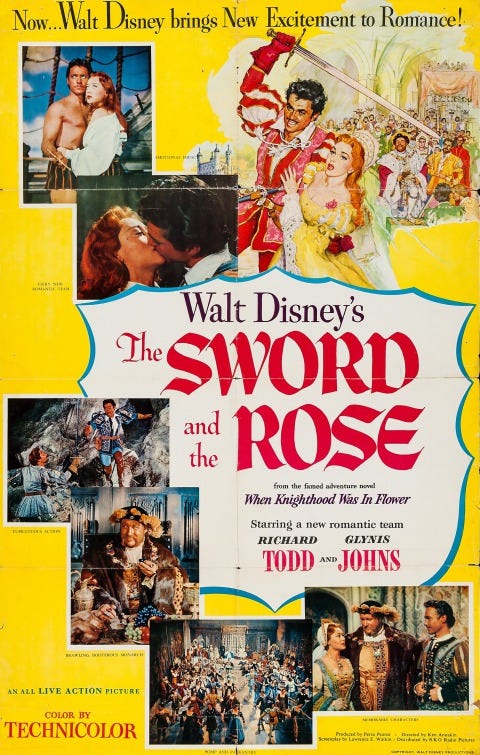

By 1953, Walt Disney British Films, Ltd was proving to be a success. Under the supervision of producer Perce Pearce, the division had made two hits: Treasure Island and The Story Of Robin Hood And His Merrie Men. Walt would periodically visit the sets, so perhaps some of the atmosphere even rubbed off on Anglo-centric cartoons like Alice In Wonderland and Peter Pan. As ambitious as ever, Walt decided to swing for the fences with his next live-action British feature. The Sword And The Rose was pure 1950s Oscar bait, a grand, big-budget romantic costume drama. But the Academy did not bite and audiences were largely unimpressed.

Pearce reunited most of his Robin Hood team, including director Ken Annakin, screenwriter Lawrence Edward Watkin, composer Clifton Parker, and stars Richard Todd and James Robertson Justice. The script was based on Charles Major’s massively popular novel When Knighthood Was In Flower, which had been filmed twice before during the silent era. New to the Disney team was an up-and-coming cinematographer named Geoffrey Unsworth who went on to such classics as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Cabaret and Superman.

Todd stars as Charles Brandon, recently returned to England from the “foreign wars”. Brandon arrives as King Henry VIII (Justice) is holding a wrestling match pitting England against France. Brandon volunteers his talents but Henry, unwilling to let a commoner represent the court, has the Duke of Buckingham (Michael Gough, the man who would be Alfred to various Batmen) step into the ring instead. After Buckingham wins, Henry’s sister, Mary Tudor (Glynis Johns) suggests that Brandon take him on. Brandon wins, Mary is smitten and Buckingham and Brandon become rivals for her affection.

At Mary’s behest, Henry appoints Brandon captain of the guards. A clandestine courtship follows. Mary loves Brandon because he’s not afraid to tell her what he really thinks. Brandon loves her because…well, she’s a rich, flirty, attractive princess. Buckingham seethes with jealousy. But the triangle is complicated by Henry’s plan to marry his sister off to the elderly King Louis XII of France.

Knowing there’s not much he can do to prevent the wedding, Brandon resigns his post and makes plans to sail for the new world. Mary runs away to join him, “disguising” herself as a boy to pose as his page. I use the term loosely because it’s the least convincing get-up in the history of cross-dressing. The ship’s crew sees through the ruse (though not as quickly as they should, considering she’s still wearing lipstick and mascara) and send the pair back to shore, where they’re picked up by Henry’s men.

Brandon is locked up in the Tower of London while Mary is shipped off to France after securing Henry’s promise that she be allowed to choose her second husband after Louis’ death. The treacherous Buckingham tells Brandon that Mary has abandoned him to his fate and arranges an “escape”, during which Brandon is apparently killed. In France, Mary does whatever she can to hasten Louis’ death, first getting him drunk, then challenging him to a horse race.

Louis succumbs to whatever illness he’s suffering from and Mary discovers that the new king is eager for her to stick around. Buckingham arrives with news of Brandon’s death and offers to marry her immediately. Just when all seems lost, Brandon returns to challenge Buckingham and win Mary’s hand. The age of chivalry lives on. Or something like that.

Ordinarily, I don’t bother with detailed plot recaps like this because I assume most people are intimately familiar with the majority of the movies we’ve discussed in this column. But it seems useful in this case, partly because the film is relatively obscure but also to help convey just how boring it is. This is not a swashbuckling adventure filled with bold knights and acts of derring-do. It’s the kind of historical romance that your grandmother may have read or watched. It’s the sort of movie that isn’t content with a five-minute ball scene showing elaborately costumed couples dancing in unison. It also needs a lengthy sequence with our leads learning the dances they’ll soon be performing. Yawn.

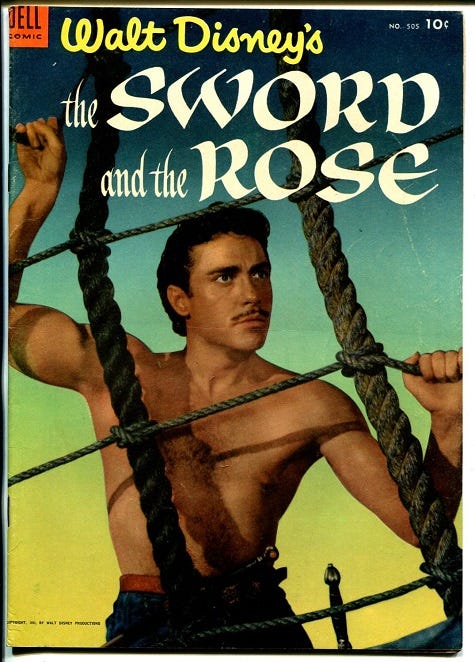

Richard Todd, who had been perfectly adequate as Robin Hood, turns in an identical performance as Brandon. He’s a fine square-jawed, twinkly-eyed leading man but he doesn’t have the presence necessary to elevate inferior material. Glynis Johns is fun and spunky enough to sort of gloss over the fact that she essentially kills the King of France. But she and Todd don’t exactly have the kind of chemistry that ignites the screen.

To be fair, this may be more Disney’s fault than the actors. On the face of it, The Sword And The Rose feels like an attempt to branch out into more adult-oriented fare. There’s nothing in the movie that would be particularly appealing to younger audiences. The action and adventure scenes are perfunctory and rare. But Disney’s idea of romance remains remarkably chaste. The result is a movie that seems explicitly designed to satisfy nobody.

There are a few things about the picture that work. James Robertson Justice, Little John to Todd’s Robin Hood, appears to be having a grand old time playing Henry VIII. And Michael Gough is effectively smarmy as Buckingham. His performance is reminiscent of Vincent Price, who was playing a lot of slimy characters in period pieces himself around this time. We’ll see all four of The Sword And The Rose’s lead actors again in this column.

This is also a nice-looking movie thanks to Unsworth’s cinematography, the lavish costumes designed by Valles, and the matte paintings of Peter Ellenshaw. Annakin used Ellenshaw’s work sparingly in The Story Of Robin Hood but he makes up for it here. Ellenshaw reportedly painted more than 60 backgrounds for The Sword And The Rose, giving the film an epic scope.

Perhaps I should say that I assume this is a nice-looking movie because the version that’s most readily available looks pretty terrible. Disney hasn’t yet made the film available on Disney+, much less Blu-ray. The only DVD release to date has been a Disney Movie Club Exclusive. You can buy or rent it online but it looks like a digitized VHS. I’m sure The Sword And The Rose doesn’t exactly have a fervent fanbase but come on, Disney. You can do better than this.

The Sword And The Rose was released in August of 1953 and landed with a resounding thud. Walt’s hoped-for Academy Award nominations failed to materialize (although he dominated the ceremony elsewhere, something we’ll get into next time). And for the first time since the war, box office returns were significantly less overseas than expected.

One theory for the UK’s lack of interest in The Sword And The Rose holds that British audiences couldn’t get past the film’s historical inaccuracies. This is absolutely the kind of “historical” drama that makes actual historians tear their hair out in frustration. Charles Brandon wasn’t some commoner that Henry chanced to meet at a wrestling match. He was one of the King’s oldest friends, having been brought up in the court of Henry VII. Brandon and Mary never attempted to escape by sailing to the new world. The English wouldn’t start colonizing America at all for another fifty years or so. Any student trying to use this movie in lieu of reading a textbook would get an immediate “F – SEE ME” in red ink slapped on their test paper.

But audiences forgive the most egregious factual errors if they’re in service of telling a ripping good yarn. The Sword And The Rose is not that. It’s a stodgy, plodding drama that doesn’t know what audience it’s trying to please. Too boring for kids and too juvenile for adults, it’s a misstep in Walt Disney’s journey into live-action filmmaking.

VERDICT: Disney Minus.