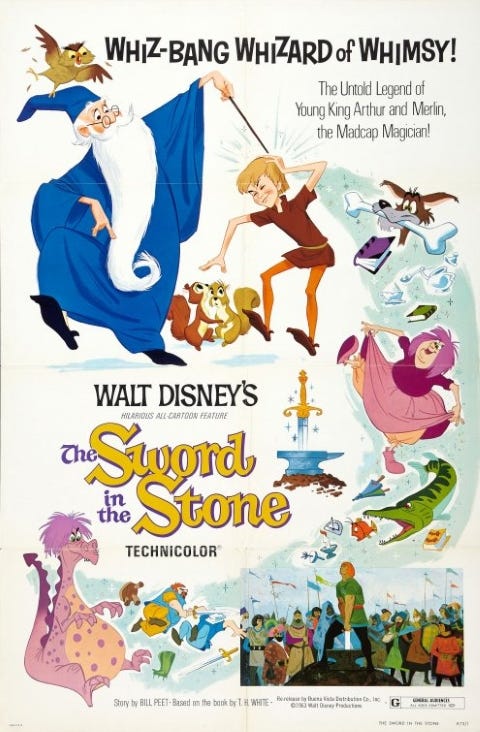

Disney Plus-Or-Minus: The Sword In The Stone

When The Sword In The Stone premiered on Christmas Day of 1963, it had been nearly three years since Disney had released an animated feature. That movie, One Hundred And One Dalmatians, had been a huge hit, a much-needed success after the costly failure of Sleeping Beauty. But it wasn’t enough to single-handedly keep the animation division off the chopping block. Roy O. Disney was still trying to convince Walt to get out of the cartoon business. And while Walt’s interests were now primarily with Disneyland and the commissioned exhibits that were scheduled to debut at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, he still had a soft spot for animation.

Cartoon production had slowed to a crawl in the wake of the Sleeping Beauty layoffs. By 1960, there were only two projects in active development. Both had been in the works for years. One of them was Chanticleer, based partly on the play by Edmond Rostand with elements of the Reynard the Fox tales. This had already been shelved once before in the 1940s. After the success of Dalmatians, animators Marc Davis and Ken Anderson tried to revive the project as a Broadway-style musical. Walt gave them his blessing provided they start fresh, without relying on any of the old concept art or story work.

In the meantime, Bill Peet was dusting off another long dormant story. Walt bought the rights to T.H. White’s The Sword In The Stone all the way back in 1939. But the project kept getting placed on the back-burner. First World War II sidetracked all feature development. By the time the studio was ready to make cartoons again, other properties like Peter Pan and Cinderella had taken priority. But Peet had an advantage over those earlier attempts. By now, there had already been a phenomenally successful adaptation of White’s work: the 1960 Lerner and Loewe musical Camelot. It was a good time to be making another King Arthur movie.

While animators Davis, Anderson, Wolfgang Reitherman, Milt Kahl and songwriters George Bruns and Mel Leven all worked on Chanticleer, Bill Peet cracked The Sword In The Stone on his own. This was practically unheard of at Disney. Since the very beginning, the story department worked in teams, crafting stories visually in marathon gag sessions. This time, Peet decided to write a screenplay before drawing the storyboards.

Ultimately, Walt worked out a compromise with Roy. He couldn’t bring himself to completely axe the animation division but he agreed to kill one of the two competing projects. At this point, Peet’s project probably didn’t appear to have much chance of surviving.

The Chanticleer team made their elaborate pitch, complete with brand new concept art (like the image above) and songs. It went over like a lead balloon. Walt had never thought a rooster made for an attractive, sympathetic hero and the new material didn’t change his mind. The jokes were flat and the music was uninspiring. The rest of the animators (and Roy) preferred Peet’s idea if, for no other reason, than because it’d be easier (and cheaper) to animate people instead of farm animals. And so, Chanticleer was dead. Again.

(Years later, ex-Disney animator Don Bluth would attempt to put his own spin on the Chanticleer idea with Rock-A-Doodle. Its reception, both from critics and at the box office, suggest that the Disney folks were right to stick it on the shelf.)

Needless to say, Bill Peet was not the most popular guy on the Disney campus after Chanticleer was killed. The team switched their focus to The Sword In The Stone, although not everyone was happy about that. In another departure from Disney’s standard operating procedure, Wolfgang Reitherman became the sole director of the film with Frank Thomas, Milt Kahl, Ollie Johnston and John Lounsbery credited as directing animators. Peet and Kahl were in charge of character design and even though Kahl had been one of the pro-Chanticleer animators who initially nursed a bit of a grudge toward Peet, he eventually grew to enjoy the new project.

Peet tried to stay relatively faithful to White’s original 1938 novel (the author later revised the book to retroactively serve as the first volume of The Once And Future King). Unfortunately, Roy and Walt demanded the project be brought in on a much, much lower budget than usual. This meant Peet couldn’t have too many characters. Large pieces of White’s book were cut, leaving Peet and Reitherman to focus on a small ensemble cast.

In theory, this shouldn’t be a big deal. The story focuses on young Arthur (or, as he’s none-too-affectionately known, Wart), ward of Sir Ector and aspiring squire to Sir Kay (played by Norman Alden, later the voice of Aquaman on Super Friends). They live more or less alone in a rundown castle until Wart drops in on Merlin the great wizard. Merlin has foreseen Arthur’s future and moves into the castle, along with his owl Archimedes, as his tutor. Merlin’s lessons consist almost entirely of transforming Wart into different animals (a fish, a squirrel, a bird) to see the world from their perspective.

The main problem with all this is that virtually nothing happens. Whatever lessons Wart is meant to learn take a back seat to gags about lovesick squirrels and dishes that wash themselves. Most movies would tie these incidents together at the climax with Arthur using these lessons to overcome some obstacle. That doesn’t happen. If he learns anything at all from being turned into a fish or a bird, it remains safely hidden.

The movie briefly comes to life when Wart runs afoul of Madam Mim. As Merlin’s archenemy, Mim decides to kill the boy out of spite. But Merlin arrives in the nick of time to challenge her to a wizard’s duel. This sequence at least has some spark and imagination in the animation. But again, Arthur is sidelined. The fight is between Merlin and Mim and doesn’t really serve a greater purpose. At least Martha Wentworth (previously heard as Nanny in One Hundred And One Dalmatians) is a delight as Mad Madam Mim.

If only Mim arrived in the story sooner. By the time she shows up, the movie is barreling toward its conclusion. Kay is summoned to London for a tournament that will decide the next King of England. Wart forgets Kay’s sword back at the inn and hurries back to collect it. Finding the inn locked up, he grabs the first sword he sees, which is, of course, the sword in the stone.

At first, no one believes his story, so they put the sword back and everyone tries to pull it out again. When Arthur demonstrates that he alone can remove the sword from the stone, the prophecy is fulfilled and he becomes King. Merlin comes back and assures him that he’ll be great. Someday, they’ll even make a motion picture about him! Sigh.

Look, The Sword In The Stone has its champions but I think it’s safe to say that this is nobody’s favorite Disney cartoon. It’s the studio’s first animated feature (as opposed to earlier package films) that can accurately be described as boring. The story is non-existent. The animation is cut-rate, recycling not only its own footage but bits from earlier films. And the hit-to-miss ratio on the gags leans heavily toward the latter.

Character actor Karl Swenson (probably best known to TV viewers of my generation as Lars Hanson on Little House On The Prairie) provides the voice of Merlin. His anything-goes spirit and use of anachronistic references makes him a bit of a precursor to Robin Williams’ Genie in Aladdin. But whatever his strengths as an actor, Karl Swenson was no Robin Williams. Merlin ends up feeling half-formed, neither particularly wise or imposing but also not as wacky and fun as he could have been. At least Madam Mim has a distinct personality.

Sebastian Cabot is a bit more successful as Sir Ector. The character design seems…let’s say, heavily influenced by the King in Cinderella. But Cabot’s booming voice suits the character well. Cabot had already appeared in a couple of Disney’s live-action features, Johnny Tremain and Westward Ho The Wagons! This was his first voice-over performance for the studio but we’ll be hearing from him again. We’ll also be hearing from Junius Matthews, the voice of Archimedes and another returning voice from One Hundred And One Dalmatians.

Originally, Wart’s voice was provided by Rickie Sorensen, a child star who could also be heard as one of the puppies in Dalmatians. But when Sorensen’s voice started to change midway through production, Wolfgang Reitherman recruited his son, Richard, to finish the job. Then Richard’s voice broke and younger brother, Robert, was put behind the mic. But instead of re-recording any of the dialogue, the finished performance is a bizarre Frankenstein’s monster of all three boys. It’s a peculiar, distracting choice. You can clearly hear the differences between the three voices. It’s a rare example of Disney underestimating his audience. Obviously everyone involved just assumed nobody would notice or care.

The Sword In The Stone also provided Richard and Robert Sherman with their first opportunity to write original songs for an animated film. Unfortunately, the songs are merely OK. For the most part, they’re catchy without being particularly tuneful or memorable. “The Marvelous Mad Madam Mim” and “A Most Befuddling Thing” are good examples. They kind of get stuck in your head but you can’t really hum them or sing along. If nothing else, they’re better than the ponderous title song.

“Higitus Figitus” is the film’s best-remembered song and I’m sure that’s by design. Merlin sings it while magically packing all his worldly belongings into a single valise. If the Shermans were not explicitly told to write another “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo” for this sequence, I’m sure the storyboards left little doubt as to what was expected of them. The sequence and the song are emblematic of the film as a whole: we’ve seen better versions of this before.

Critics and audiences tended to agree with that assessment. Reviews were mixed and even the most enthusiastic notices tended to be a bit lukewarm. It earned less than $5 million at the box office, enough to turn a small profit but a fraction of what One Hundred And One Dalmatians (or even Son Of Flubber) had pulled in.

The Sword In The Stone has its moments and for some, those high points may be enough. But overall, the film is a colossal disappointment. An animated Disney telling of Arthurian lore sounds like the sort of movie that should be an event. Instead, it’s a missed opportunity and a sign the once-mighty studio that had once been at the forefront of animated storytelling had begun to lose its touch.

VERDICT: It’s not terrible but compared to what had come before? It’s a Disney Minus.