Disney Plus-Or-Minus: Tonka

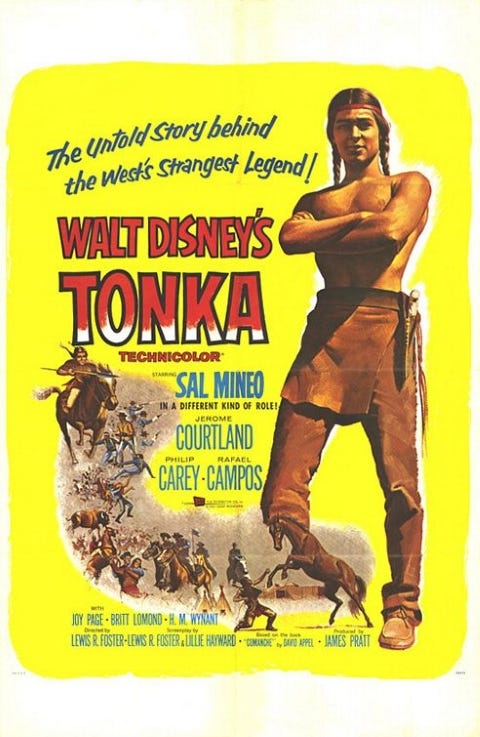

By the end of 1958, Disney’s live-action division was stuck in a bit of a rut. They’d enjoyed some huge hits like Treasure Island, Davy Crockett and 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea. But those were exceptions, not rules. They were known more for historical adventure pictures mixing fictional characters with real-life events. From UK productions like The Sword And The Rose to the Revolutionary War exploits of Johnny Tremain to the Civil War adventure The Great Locomotive Chase, the studio had applied the same basic formula no matter what the historical setting. That didn’t quite come to an end with Tonka, the 1958 western directed by Lewis R. Foster, but it became a much less frequent occurrence.

Academy Award nominee and noted non-Native American actor Sal Mineo stars as White Bull, a headstrong Sioux brave. After spotting a spirited colt running with a band of wild horses, White Bull “borrows” a coveted rope from his cousin, Yellow Bull (equally non-Native H.M. Wynant). White Bull loses both the rope and his bow and arrows in his attempt to capture the horse, leading Chief Sitting Bull (actual Sioux John War Eagle) to forbid him from participating in future hunts.

White Bull goes out to find his lost bow and finds the horse, who he’s already named Tonka Wakan (the Great One), completely tangled up in his cousin’s rope. He constructs a makeshift enclosure, frees the horse and slowly and patiently begins training Tonka. After some time, he triumphantly returns to his tribe with Tonka. But Yellow Bull isn’t satisfied with just getting his rope back. He pulls rank and claims Tonka for his own.

The horse refuses to cooperate, responding only to White Bull’s more gentle hand. Knowing he can’t reclaim the horse from his older cousin but unable to bear watching him suffer, White Bull does the only thing he can: he sets the horse free.

Tonka rejoins his band but his freedom is short-lived as they’re caught in a round-up (led by Slim Pickens, making his second Disney appearance). The cowboys sell the horses to a cavalry outfit where Tonka catches the eye of Captain Myles Keogh (Philip Carey). Keogh sees that Tonka has been well-trained and responds to gentle, patient instruction. Renaming the horse Comanche, Keogh claims him for his own and grows to love him almost as much as White Bull.

With reports of Sioux converging on the area, Keogh reports to General Alfred Terry (Sydney Smith) and General George Armstrong Custer (Britt Lomond). While the cavalry troops formulate a plan of attack, White Bull volunteers for a reconnaissance mission. He sneaks into the fort and while reuniting with Tonka is caught by Keogh. The two enemies bond over their shared horse. Keogh turns White Bull in for questioning but promises he won’t allow anyone to hurt him. The next morning, Keogh lets White Bull go, hoping they’ll never meet on the battlefield.

The cavalry forces split up with strict orders not to attack until they’re together again. But Custer, who is depicted as nothing short of genocidal when it comes to the Indians, hears a report of an isolated group in the valley of Little Bighorn. Custer decides they’d be stupid not to attack and we all know how that turned out.

Miraculously, both White Bull and Tonka survive the battle. Tonka/Comanche becomes an honored war hero, the only survivor of the attack on the cavalry side. He’s retired from active military service and White Bull is made his official caretaker, the only one allowed to ride Tonka from now on. In the wonderful world of Disney, even Custer’s Last Stand somehow has a happy ending.

Now you might be thinking that Walt Disney is an odd choice to make a movie based on one of the bloodiest skirmishes in the annals of the American West. You would be correct. It’s based on the novel Comanche by David Appel. Comanche was a real horse who did survive the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Like Black Beauty, Appel’s book is told from the horse’s point-of-view. The movie can’t quite replicate that narrative trick, opting instead to tell the story primarily from White Bull’s perspective.

The title change from Comanche to Tonka is indicative of the film’s new focus but the actual reasoning behind it is more mundane. Another unrelated western called Comanche had just been released a couple years earlier, so screenwriters Lewis R. Foster and Lillie Hayward changed their title to avoid confusion.

The idea of telling the story of Little Bighorn from the Sioux’s point of view is a good one, as would be demonstrated years later in the novel and film Little Big Man. In some ways, Tonka is a bit ahead of its time, especially in its depiction of Custer as the villain. Custer was frequently seen as a tragic hero in those days. That was the image presented by Errol Flynn in the wildly inaccurate biopic They Died With Their Boots On. Lomond plays him as a vain, half-crazed racist. Carey is frequently seen casting some skeptical side-eye at his fellow officer.

None of this lands with much force, partly because Britt Lomond is sort of bland in what should be a role that lends itself to showboating. Lomond had already appeared as a Disney villain on TV, playing the ruthless Captain Monasterio on Zorro (Zorro will eventually appear in this column). Television seemed to be his natural element as he never did quite break into film as an actor. Eventually he started working behind the camera as a production manager and assistant director on such features as Somewhere In Time and Purple Rain.

It would be one thing if Lomond’s uninspired performance was an isolated misstep in casting. Unfortunately, it’s fairly typical of the film in general. Philip Carey brings something of a Troy McClure vibe to the role of Captain Keogh. This was presumably the role Fess Parker refused to play and it’s easy to see how his laid-back, sympathetic nature would have lent itself to the part. But it also would have been one more ever-so-slight variation on his Davy Crockett persona, so it’s hardly surprising Parker walked away from it. Carey is more broad-shouldered and square-jawed but you never feel like he believes in what he’s doing the way Parker did. Fess Parker may have been somewhat limited as an actor but at least he oozed sincerity. Carey is just another handsome actor playing dress-up.

Carey never made another Disney movie but he went on to an eclectic career in film and television. He went back to Little Bighorn, this time as Custer, in the 1965 western The Great Sioux Massacre. In a classic episode of All In The Family, he appeared as Archie Bunker’s ex-football player buddy who shocks Archie by revealing that he’s gay. And in 1980, he joined the cast of the long-running soap opera One Life To Live, a role he’d continue to play for nearly 30 years.

Jerome Courtland played Keogh’s second-in-command, Lieutenant Henry Nowlan. Courtland has already appeared in this column, although I didn’t realize it at the time. He sang the title song for Old Yeller. On TV, Courtland played the title role in The Saga Of Andy Burnett, another of Walt’s Davy Crockett wannabes. By the end of the 1960s, Courtland had moved behind the camera. He’ll be back in this column as a producer and director.

Sal Mineo was already a major star when he made Tonka and it’s a little hard to imagine what brought him to the Disney lot. Walt wasn’t a fan of working with established movie stars, preferring to cultivate his own talent. And it isn’t as though he didn’t already have plenty of young men in that age range under contract, especially if casting an actual Native American actor wasn’t a priority.

Mineo had been nominated for an Oscar for his work in Rebel Without A Cause and reteamed with James Dean in his final film, Giant. So Sal Mineo was very much wrapped up in the Dean Mythos that began to appear immediately after his death. In the years since, he had cornered the troubled teen market in movies like The Young Don’t Cry. For Mineo, Tonka was a chance to break out of that box and show audiences he could do more than just brood.

To some extent, he’s successful in his attempt. He smiles a lot more in Tonka than in any other film I’ve seen him in. It’s a very physical role and he seems confident and comfortable with his equine costar. He’s not equally at home with all the action. His handling of a bow and arrow is particularly awkward. And in 1958, even the most sensitive portrayals of Native Americans lapsed into the cartoonish and stiff broken English of Tonto.

Tonka represents some baby steps in the right direction toward more positive depictions of Native Americans on screen. But it still relies on slathering up primarily white actors with bronzer, sticking black wigs and feathers on their heads and calling it good. Foster may have had good intentions but he lacks authenticity. Without authenticity, it’s easy to doubt his sincerity.

Ultimately it’s a lack of clear focus that sinks Tonka. Is it an inspiring story about a young man and his horse? Or is it a violent western retelling a dark chapter in American history? Foster isn’t really equipped to turn in more than a fun adventure story but the Battle of the Little Bighorn could hardly be described as “fun”. In the end, Tonka doesn’t seem to know what it’s trying to accomplish beyond showcasing all these magnificent horses.

Tonka was released on Christmas Day 1958. It was no blockbuster but it did a respectable amount of business. But Walt’s next live-action feature would be a blockbuster and its success meant that he’d be spending a lot less time and money on historical adventures. They wouldn’t disappear entirely but after Tonka, they would no longer be the studio’s primary live-action focus.

VERDICT: Disney Minus.