If you’d like to see a stark example of how much times had changed between the 1960s and the ‘90s, try watching a double feature of 1991’s White Fang with 1961’s Nikki, Wild Dog Of The North. White Fang opens with a disclaimer that reads, “All animals in this production were trained with care and concern for their safety and well-being. Scenes which appear to be harmful to them were simulated.” There is no such reassuring hand-holding in Nikki. Within the first 15 minutes of that film, you’ll get to see a very real Malamute tied to a very real bear cub and sent shooting down a violently churning river. Every once in a while, things can change for the better.

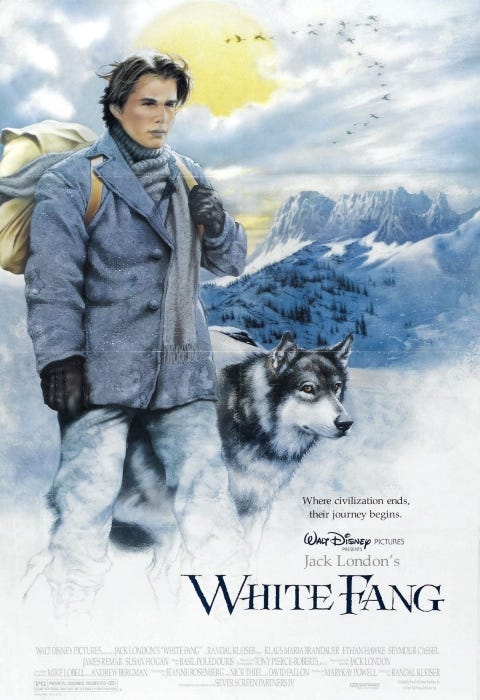

White Fang was based on the 1906 novel by Jack London and it’s more than a little surprising that we haven’t already seen a Jack London adaptation in this column. Filmmakers loved London’s work dating back to the silent era. White Fang alone had been filmed no less than four times prior to the Disney version. Considering how many nature movies Walt produced, you’d think he’d have gotten around to Jack London at some point.

The studio had been trying to get White Fang off the ground for a few years, at least since 1988. Executive producer Mike Lobell, who had produced The Journey Of Natty Gann for Disney, developed the project with his partner, Andrew Bergman, the writer of such films as The In-Laws. The first draft of the screenplay was by Natty Gann writer Jeanne Rosenberg. Subsequent drafts were turned in by Nick Thiel, a former TV writer perhaps best known at the time for the time-travel adventure Voyagers!, and David Fallon. Fallon was just completing his latest set of revisions when a Writers Guild strike shut down production. The strike lasted five months, five days longer than the recent 2023 strike that crippled Hollywood.

By the time the strike ended in August of 1988, everyone was eager to get back to work. To direct, Lobell and Bergman hired Chris Menges, the Academy Award-winning cinematographer of such films as The Mission who had recently made his feature directorial debut with A World Apart. But casting delays and the logistics of planning a complicated location shoot in Alaska forced Menges to drop out of the project. He was replaced by Randal Kleiser, the director of Flight Of The Navigator and Grease.

London’s book was told from the perspective of its title character but Kleiser’s White Fang really tells two stories that eventually converge. The first track follows Jack Conroy (played by Ethan Hawke, who’d made his Disney debut in 1989 with Touchstone’s Dead Poets Society), a young man from San Francisco who arrives in Alaska to seek out his late father’s gold claim. He tracks down his dad’s former associates, Alex Larson (top-billed Klaus Maria Brandauer) and “Skunker” Thurston (Seymour Cassel, who had recently appeared in Touchstone’s Tin Men and Dick Tracy). Alex and Skunker are on their way to bury their deceased partner at the site of his claim but Alex very reluctantly agrees to bring Jack as far as Klondike City. Jack has to adapt to the unforgiving environment quickly and learns how fast things can change when Skunker is killed trying to fend off a pack of hungry wolves.

Meanwhile, the film also follows a young wolf-dog who is orphaned after his mother is killed while running with the pack that attacks Skunker. The cub is rejected by the pack and is forced to make it on his own, even briefly encountering Jack. Eventually, he finds himself ensnared in a trap set by a tribe of Native Americans. The chief, Grey Beaver (Pius Savage), decides to raise the pup to be a working dog and names him White Fang.

After spending the winter in Klondike, Jack finally persuades Alex to take him to his father’s claim. On the way there, they stop to rest with Grey Beaver and his tribe. Jack is reunited with White Fang (now played by Jed, the canine costar of Natty Gann), who rescues him from a bear attack (the bear is played by Bart the Bear, who had appeared in Benji The Hunted before starring in the 1988 adventure The Bear).

While Jack and Alex get to work setting the claim to rights, Grey Beaver heads into Klondike with White Fang to sell some furs. There, White Fang attracts the attention of Beauty Smith (James Remar), an unscrupulous crook who wants White Fang as a fighting dog (it’s a Disney movie set during the Gold Rush, so you know there’s gonna be dogfights). Beauty provokes a fight between White Fang and his own Saint Bernard, Buck (the same dog from London’s The Call Of The Wild), and threatens to have Grey Beaver arrested unless he gives up White Fang.

White Fang responds to Beauty’s abusive training and becomes an undefeated fighting dog until he’s matched with an aggressive pit bull. Jack and Alex just happen to be in town during the fight and Jack recognizes White Fang. He’s able to stop the savage fight before the wolf-dog is killed and takes him back to his father’s place to nurse him back to health. But Beauty Smith isn’t the kind to forgive and forget. Before long, he leads his cohorts Luke and Tinker (Bill Moseley and animal trainer Clint Youngreen) in an attack on Jack’s mine.

Obviously, we’ve seen a whole lot of movies that are very similar to White Fang in this column. And yet, Randal Kleiser and his team deliver a highly entertaining movie despite its familiarity. A big chunk of the credit for that goes to cinematographer Tony Pierce-Roberts, an Oscar nominee for his work on the Merchant-Ivory films A Room With A View and Howards End. White Fang is worlds away from the Edwardian drawing rooms of those pictures and Pierce-Roberts does a fantastic job capturing the rugged Alaskan vistas, especially in an early sequence depicting Jack and other would-be miners scaling the treacherous Chilkoot Pass, otherwise known as the Golden Stairway.

The performances are uniformly excellent and the film’s authenticity is helped by casting decidedly non-Disney actors like Brandauer, Cassel, Remar and Moseley. Ethan Hawke had only made a few films prior to White Fang. In addition to Dead Poets Society, he’d debuted in Joe Dante’s Explorers and appeared in a supporting role alongside Jack Lemmon and Ted Danson in the family drama Dad. White Fang was his first real lead outside of an ensemble and he’s more than up to the task. Ethan Hawke will continue to pop up in this column on both the Disney and Touchstone sides.

White Fang was released on January 18, 1991, historically not a great time of year for new movie releases. Its competition that weekend was mostly holdovers from the 1990 Christmas season and newcomers like Flight Of The Intruder and Not Without My Daughter, movies that have probably not been occupying too much of your mind over the past thirty-plus years. Critics liked it generally, although they weren’t exactly gushing over it, and it opened in sixth place with over $5.5 million. It continued to hang around the top ten for a month and ended its theatrical run with a respectable $34 million.

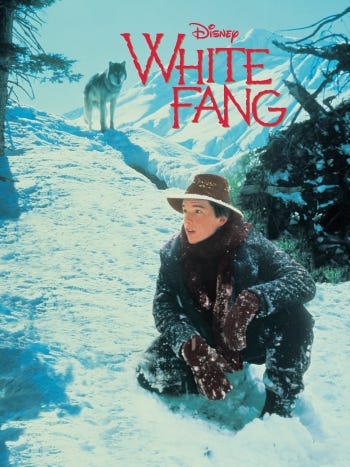

White Fang continued to build on its minor theatrical success once it hit home video and cable. It also did well overseas, becoming the fourth highest-grossing film of 1991 in France. As a result, Disney greenlit a sequel, White Fang 2: Myth Of The White Wolf, which we will get to here in due course.

While some of the techniques may have changed and Disney had definitely become more conscientious about humanely treating their animal actors, White Fang proved that the studio still knew their way around a good, old-fashioned nature adventure. In fact, the 1990s would see the genre make a bit of a comeback. The success of White Fang helped pave the way for more dogs, cats, horses and other animals on the big screen. The nature movie was far from over inside the Magic Kingdom.

VERDICT: Disney Plus

I believe Bart was also in Legends of the Fall. Quite the career he had.