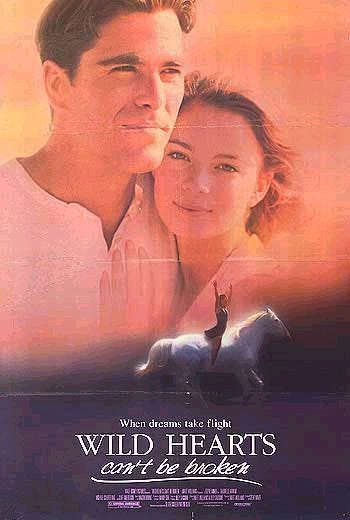

Disney Plus-Or-Minus: Wild Hearts Can't Be Broken

Believe it or not, I do a fair amount of research for this column. In addition to my own hot-and-cold takes, I try to include a little something about the who’s, why’s and how’s behind each movie so that we all discover something new about these often-familiar titles. That isn’t always possible. Some of these movies, especially the older ones, are obscure for a reason. Even then, I try to connect the dots and piece things together as best I can. But sometimes a movie comes along that stymies me. Maybe the filmmakers haven’t done a lot of interviews about it or the publicity at the time was half-hearted. Case in point: 1991’s inspirational horse-diving movie Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken. This frustrates me, not because the production itself seems all that interesting but because I’d really like to know how this particular group of people came together to tell this story at Disney.

The film tells the story of Sonora Webster Carver, a Georgia girl who essentially ran away to join the circus, becoming a sensation as a horse-diving girl. Horse-diving, for those of you who didn’t grow up with flagpole-sitting and dance marathons, was a popular sideshow attraction in the early 1900s in which a girl at the top of a 40-or-so-foot ramp would jump onto the back of a galloping horse and plunge into a pool below. Somehow, this did not become an Olympic event. Sonora was one of the most celebrated practitioners of this somewhat dubious pastime, an accomplishment made all the more remarkable by the fact that she performed while blind for many years without the audience realizing.

By the 1980s, Sonora had published a memoir (A Girl And Five Brave Horses, published in 1961), retired and was living in New Orleans. Here, she met Oley Sassone, a musician and aspiring filmmaker volunteering for The Lighthouse for the Blind. Sassone would begin his filmmaking career directing music videos for such artists as Eric Clapton, Mr. Mister and Wang Chung, making the leap to movies and TV in the early 1990s. But his best-known work is most likely the one that was never officially released, the notorious Roger Corman-produced version of The Fantastic Four.

At any rate, Sassone got to know Sonora and was fascinated by her stories. At first, he simply wanted to make a short documentary about her. He called up an old friend, Matt Williams, who had moved to New York to make it as a writer and actor. Williams later became a comedy writer for television, co-creating the sitcoms Roseanne and Home Improvement. Williams convinced Sassone that Sonora’s story sounded like a feature and together, they put together a screenplay.

Here's where things get a little fuzzy. The script wound up at Disney with Williams producing. To direct, they hired Steve Miner. Miner started his career with producer Sean S. Cunningham, making his directorial debut on Friday The 13th Part 2. Since then, he’d worked almost exclusively in horror, helming Friday The 13th Part III, House and Warlock. His only foray outside the genre had been the C. Thomas Howell in blackface comedy Soul Man. Now, I’m sure the backstory here is nowhere near as interesting as I’d like to imagine. This probably all came together the usual boring way with agents, lawyers and that kind of thing. Still, it’s an unusual group of folks to make a heartwarming kids movie for Disney.

Gabrielle Anwar, a British actress who had recently relocated to the States, was selected to play Sonora Webster. Coincidentally, her next film would also revolve around the visually impaired as she tangoed with a sightless Al Pacino in Scent Of A Woman. Anwar was 21 when she made Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken but certainly looks young enough to convincingly portray 15-year-old Sonora. When we first meet her, she and her little sister are living with their aunt after the death of their parents. Sonora dreams of a life outside of Waycross, Georgia, and when her aunt threatens to turn her over to the state, she seizes the opportunity to hit the road.

She heads to Savannah, intending to reply to an ad seeking horse-divers placed by Wild West showman Doc Carver (Cliff Robertson). Carver dismisses her as too young and weak to be a diving girl but begrudgingly agrees to take her on as a stable hand, bringing her home with his star attraction, Marie (Kathleen York, who would later be an Oscar-nominated songwriter for “In The Deep” from the movie Crash), and his gambler son, Al.

Al is played by Michael Schoeffling, best known as Jake Ryan, the object of Molly Ringwald’s crush, in Sixteen Candles. This would turn out to be Schoeffling’s last acting gig. After filming Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken, he decided he’d had enough of the Hollywood rat race and left the industry entirely. Schoeffling returned to his home state of Pennsylvania to make hand-crafted furniture, a vocation he seemingly enjoys to this day. I say “seemingly” because once he left Hollywood behind, he stopped giving interviews and hasn’t even publicly revealed the name of his store. You have to admire his dedication to pursuing anonymity.

Back at Doc Carver’s place, Al wins a wild, unbroken horse in a poker game that Doc doesn’t believe can be trained. Wanting to prove herself, Sonora names the horse Lightning and sets about training the horse with Al’s help. After a lot of trial and error, Sonora manages to bring the horse in line and begins training to be a diving girl. But the friction between Al and his father grows into outright hostility. After an especially contentious fight, Al leaves home, promising to write Sonora every day.

Sonora gets her big break when Marie dislocates her shoulder while attempting to ride Lightning. Doc is impressed but Marie, unsurprisingly, doesn’t want to share billing with a younger rival and leaves to make it in the pictures. The show begins to have a hard time finding bookings amid the Great Depression. Just as things seem their bleakest, Al returns with a surprise. He’s signed a contract to do the show in Atlantic City on the Steel Pier. The group heads north but Doc passes away before they make it, leaving Al in the uncomfortable position of introducing the act.

They’re not in Atlantic City for long before Sonora has her accident, leaving her eyes open at the moment she impacts the water. Marie is called in to take her place and Sonora has a difficult time adjusting, refusing at first to believe that her condition is permanent. But, indomitable spirit that she is, she pushes herself to ride even without the benefit of sight.

For the most part, Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken is a perfectly serviceable, if utterly predictable, story of overcoming the odds and following your dreams. The period flavor isn’t quite as lived-in as The Journey Of Natty Gann but I always enjoy movies about the forgotten fringes of show business. The cast is fine, especially Gabrielle Anwar and Cliff Robertson. A lot of people who saw this movie when they were kids seem to love it and more power to them. They have nothing to feel ashamed about.

The movie’s biggest problem is there is absolutely no sense of how much time is passing. The whole thing seems to be compressed into about a year, if that. When the first stirrings of romance begin to develop between Sonora and Al, my first reaction was, “Ew.” Wasn’t she just 14 and causing trouble in a one-room schoolhouse? Isn’t he in his late 20s? It doesn’t help that Anwar is playing younger than her actual age and Schoeffling is about a foot taller than her, making her look even more like a child. Their relationship seems to go from brother-sister to husband-wife in the wink of an eye.

The movie also makes it appear that Sonora’s accident occurred immediately upon arrival in Atlantic City. That’s not what actually happened. In real life, they’d been performing on the Steel Pier since 1929 before the accident took place in 1931. That also means Sonora was 27 and had been performing for more than a decade at that point. You get no sense of that in the movie. By the time the extraordinarily abrupt ending rolls around, Sonora still seems like a teenager. It’s hard to repress a laugh at that ending, in which Sonora informs us via voiceover that, oh yeah, she and Al got married and lived happily ever after.

The real-life Sonora Webster Carver was reportedly not happy with the dramatic license taken by the filmmakers. Among other things, she disliked the implication that Al and his father ever resorted to physical violence and that the movie completely forgets about her little sister, ignoring the fact that she eventually joined Sonora in the act. She lived for nearly a decade after the movie loosely based on her life came out, passing away in 2003 at the ripe old age of 99.

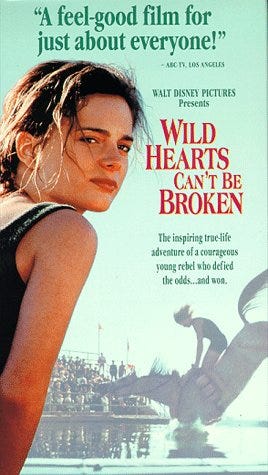

Disney released Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken on May 24, 1991. Releasing the film on Memorial Day weekend could either be seen as a clever but risky attempt at counterprogramming or a suicide mission. Critics didn’t think much of the movie, although a few liked it well enough, and it opened in a distant seventh behind Backdraft, Touchstone’s What About Bob?, Bruce Willis’ Hudson Hawk, Thelma & Louise and even Drop Dead Fred. Its fortunes did not improve in the weeks to come. It ended up with just over $7 million, although it found a more appreciative audience once it hit home video.

Despite being inspired by a colorful true story and the somewhat unusual pedigree of its creators, Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken doesn’t bring anything new to the table. While Disney Animation was steadily trying to push the art forward, the live action division appeared to be spinning its wheels, afraid to take too many risks. As a result, too many of their ‘90s movies feel the same: competently made but ultimately forgettable.

VERDICT: Disney Neutral