Disney Plus-Or-Minus: Never Cry Wolf

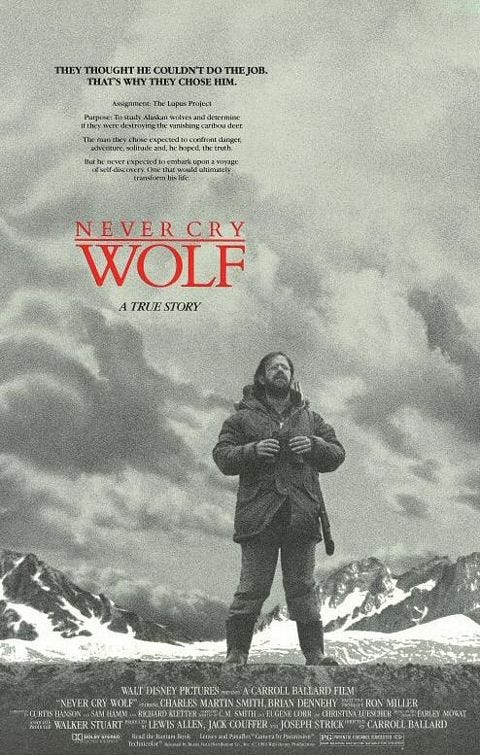

For much of the 1980s, Disney President and, as of 1983, CEO Ron Miller had been rolling the dice on movies that did not fit comfortably within the Disney wheelhouse. Projects like Night Crossing, Tron, Tex, Trenchcoat and Something Wicked This Way Comes had little in common apart from how different they all felt from the traditional Disney model. But he evidently could still find room for at least one tried and true genre: the Disney nature film. On paper at least, Never Cry Wolf appears very similar to the nature films of the 1950s and 60s. But with director Carroll Ballard at the helm, the film itself feels very different from those earlier works.

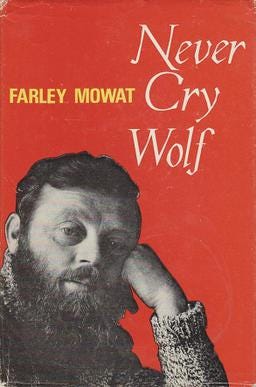

The film was based on a 1963 book by Canadian environmentalist Farley Mowat. Mowat based the book on his own experiences observing the behavior of Arctic wolves in the wild. While the book received its share of criticism for fictionalizing some of Mowat’s adventures, it was still a popular success and helped change the public perception of wolves as bloodthirsty killers.

Attempts to adapt Mowat’s book to the screen date back to at least the late 60s. In 1969, it was announced that Warner Bros. had picked up the rights with Academy Award nominated screenwriter Millard Kaufman working on the script and Jack Couffer attached to direct. Couffer was a veteran of the True-Life Adventures series and the codirector of Nikki, Wild Dog Of The North. Kaufman’s work wasn’t used but Couffer retained a producing credit on the finished film.

By 1974, the project was under the auspices of producers Lewis Allen and Joseph Strick. Nothing on either of their resumes suggested they’d ever want anything to do with Disney. Allen was a theatre and film producer with such credits as Peter Brook’s Lord Of The Flies and François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451. In 1977, he’d win the first of three Tony Awards for producing the musical Annie (granted, that one may have caught Disney’s attention). Strick was an independent filmmaker known for tackling “unfilmable” literary adaptations like James Joyce’s Ulysses and Henry Miller’s Tropic Of Cancer. Allen and Strick first teamed up on Strick’s 1963 film of Jean Genet’s play The Balcony, which is about as far removed from Disney as you can get.

The screenplay for this version of Never Cry Wolf was written by Jay Presson Allen, the Oscar-nominated screenwriter of Cabaret and Lewis Allen’s wife, and future L.A. Confidential director Curtis Hanson. Ultimately, Presson Allen would not be credited on Never Cry Wolf but Hanson was, the first of six credited writers on the finished film including Sam Hamm, who would go on to write Tim Burton’s Batman, and Richard Kletter. The director was to be Louis Malle, the acclaimed French filmmaker who had recently broken into English-language features with the decidedly un-Disney-like Pretty Baby.

Somewhere in the middle of all this, Warner Bros. dropped out of the project and Ron Miller aggressively pursued the rights. In some ways, this makes complete sense. After all, Disney had practically invented the modern nature movie. Their formula worked and by the time Mowat’s book came out in 1963, they could practically turn them out in their sleep. And quite frankly, that frequently seemed to be exactly what they were doing. Miller had no interest in making another King Of The Grizzlies or The Bears And I. He wanted his studio involved in something more ambitious.

Perhaps not too surprisingly, Allen and Sitrick were not too eager to have their project completely swallowed by Disney. So Miller reached a deal with the team to allow the film to continue as an independent production released under the Disney banner. Plenty of other studios had made arrangements like this but this was a first for Disney, who had always preferred to keep everything in house (although they had teamed up with Paramount on a limited basis to co-produce Popeye and Dragonslayer).

Bringing Louis Malle into the Magic Kingdom would have been a clear sign that this was no ordinary Disney movie. But when Malle dropped out, Miller found an equally interesting replacement. Carroll Ballard was a graduate of the UCLA film school and a classmate of Francis Ford Coppola. He’d made several acclaimed documentaries, including the Oscar-nominated Harvest, and done second unit work on Coppola’s Finian’s Rainbow and George Lucas’s Star Wars. In the late 70s, Coppola was producing an adaptation of the children’s novel The Black Stallion and hired Ballard to direct. Ballard absolutely nailed the assignment. The Black Stallion exceeded critics’ expectations, earned a couple of Oscar nominations and was a hit with audiences.

One of the film’s biggest challenges was always going to be finding the right actor to play Tyler, the Farley Mowat surrogate. This person needed to be deeply committed to a physically demanding production and compelling enough to hold an audience’s attention, as Tyler spends a great deal of the movie isolated and alone. Based on his previous appearances in this column in No Deposit, No Return and Herbie Goes Bananas, Charles Martin Smith might not appear to be the most intuitive choice for the role. But Ballard found an ideal collaborator in Smith. The actor worked on the film for nearly three years, two of them shooting on location, even earning a writing credit for his work on the film’s narration. At 5’4”, he’s not a physically imposing figure, which works to the movie’s advantage by emphasizing just how insignificant he appears against this vast, imposing backdrop. But his intense, inquisitive gaze can lock into the camera and draw the audience in, making you feel every discovery and hardship Tyler experiences.

Smith also struck up a friendship with the real Farley Mowat while making Never Cry Wolf. Years later, after he’d turned his attention to directing and writing, Smith returned to the Canadian wilderness to direct the 2003 film The Snow Walker, based on a short story by Mowat. As an actor, Smith continued to appear in movies like The Untouchables and Starman but we probably won’t be seeing him in this column again, although we will get to see him in action behind the camera.

Tyler is sent north by the Canadian government to test the theory that wolves are responsible for the country’s declining caribou population. Dropped off in the middle of nowhere by pilot Rosie Little (Brian Dennehy, a welcome presence any time he turns up on screen), Tyler struggles for survival. He gets a little help from an old Inuk named Ootek (Zachary Ittimangnaq) but after he disappears, he’s on his own.

Eventually he spots a family of Arctic wolves and sets up camp to observe their behavior. During this stretch, the film could almost be about the making of one of Disney’s True-Life Adventures. Tyler still hasn’t seen a single caribou, however. He theorizes that the wolves, who he names George and Angeline, survive on a diet of field mice. He tests the theory on himself, chomping into Mickey’s northern relations with relish.

After months of isolation, Ootek reappears with a younger Inuk named Mike (Samson Jorah). Ootek grows to respect and understand Tyler’s methods and assures him that the wolves are not responsible for the vanishing caribou. If anything, they are a vital part of the food chain, killing only weak and diseased caribou so the herd can survive. Ootek agrees to lead Tyler on a three-day hike to where the caribou have gathered while Mike heads north with the rest of his family.

Sure enough, Tyler sees for himself that the wolves do not kill indiscriminately. But soon thereafter, he finds Rosie leading an expedition of rich white hunters. These are the caribou killers Tyler has been sent to discover. Refusing to return to civilization with Rosie, Tyler heads back to his camp only to discover that George and Angeline are gone, their pups abandoned. But it wasn’t Rosie’s hunters who were responsible. This time, it’s Mike, who sells wolf pelts himself to survive.

Never Cry Wolf boasts a more nuanced approach to this kind of environmental, circle-of-life-type story than one might expect. Disney has come out against sport hunting in their movies before (see Run, Cougar, Run if you can find it). But it’s rare to see a character like Mike. On the one hand, it’s impossible to begrudge him his ability to earn a living, feed his family or even fix his toothless grin with a gleaming set of false teeth. But he’s clearly moving away from the traditions of his people and edging closer toward the creature comforts of the white men. The last we see of him, he’s snapping a picture of Tyler with a new camera, as if Tyler himself is now the interesting specimen.

Ballard directs the film with subtlety, humor and a genuine sense of danger. I first saw Never Cry Wolf in the theatre back in 1983. To this day, I have never forgotten the scene where Tyler breaks through the ice of a frozen lake or the remarkable sequence with Tyler running nude amidst the herd of caribou. (For the record, this is not the first glimpse of nudity in a Disney movie. Pollyanna opened with a kid’s butt all the way back in 1960. But Smith does have the distinction of being the first naked adult in a Disney movie, which probably isn’t enough to qualify him as a Disney Legend but sure ought to.)

As good as some of the footage in the True-Life Adventures and other Disney nature movies was, the cinematography in Never Cry Wolf blows it out of the water. Ballard and director of photography Hiro Narita capture genuinely breathtaking images of the Canadian landscape. This was Narita’s first Disney credit but it won’t be his last. He returned as cinematographer on several live-action Disney movies of the 1990s, including The Rocketeer and Hocus Pocus.

Never Cry Wolf also marked the first film score for trumpeter and keyboardist Mark Isham. Isham went on to become a prolific film composer, earning an Oscar nomination for A River Runs Through It. The fact that his music here leans heavily on the synthesizer may date it a bit but it’s still undeniably effective and often beautiful.

Disney released Never Cry Wolf on October 7, 1983 (ironically, the same day as another “never” movie, Never Say Never Again). It started in limited release and gradually built word of mouth as it rolled out across the country. The strategy worked. The movie had legs, continuing to play into 1984 and eventually earning north of $27 million. It was the first movie to actually turn a profit that Disney had released in quite some time.

Critics also admired the picture and the film even got Disney an Academy Award nomination for Best Sound. It lost the award to The Right Stuff which, honestly, makes sense. It’s a little surprising that Narita didn’t get a nod for Best Cinematography, especially when you consider that WarGames did. Nothing against WarGames, which I love, but the look is not the first thing I think of when I think of that movie. But I suppose that’s show biz.

Never Cry Wolf was a real triumph for Carroll Ballard, Charles Martin Smith and Disney. It remains a high point in the studio’s period of risk-taking and experimentation. Sadly, the studio has never bothered to release it on Blu-ray or even make it available on Disney+ and the DVD release appears to be out of print. This is a movie that deserves to be preserved in the highest possible quality and distributed widely, not allowed to vanish into semi-obscurity.

VERDICT: A very big Disney Plus.

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!