In geek culture, 1982 is held up as a sort of annus mirabilis, a year that offered untold pop culture riches. It’s the year that gave us E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Poltergeist, Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan, Blade Runner, John Carpenter’s The Thing, Conan The Barbarian and the list goes on. My old friend and occasional Digital Bits contributor Mark A. Altman recently produced a whole documentary about it that ran on The CW and I’ve participated in a few panels on the subject on the convention circuit.

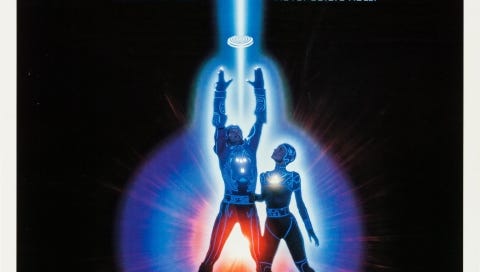

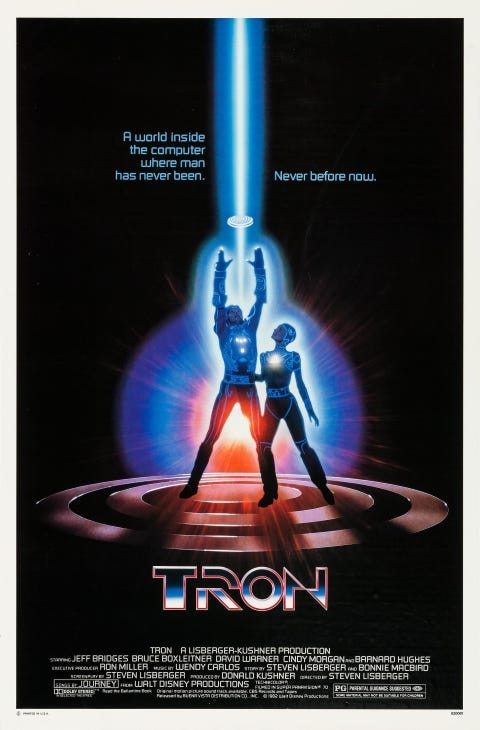

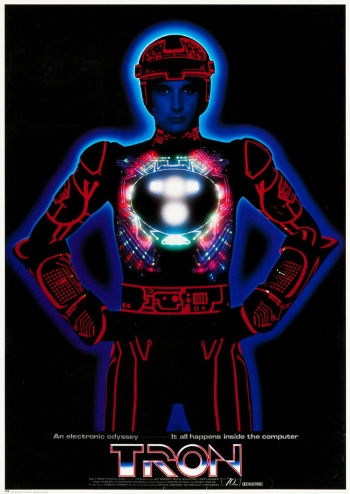

Based on the recent history covered in this column, you wouldn’t necessarily expect Walt Disney Productions to be a part of that conversation. And yet, smack dab in the middle of an otherwise unremarkable if not downright disappointing year, Disney released Tron, their most ambitious and innovative movie in years. It was not, by any means, an out-of-the-gate success. But it has endured to emerge as one of the few Disney movies that can genuinely be considered a cult classic.

Tron was not necessarily meant to be a Disney film. The film’s inspiration dates back to 1976 when writer-director Steven Lisberger, an independent animator and producer, was introduced to the world of video games via the groundbreaking Pong. Lisberger began concocting a story that would take place within the computer itself. In the meantime, his independent animation house, Lisberger Studios, kept active producing commercials, title sequences and Animalympics, a spoof of the Olympic Games featuring such voice talent as Billy Crystal, Gilda Radner and Harry Shearer. Animalympics was commissioned as a two-part TV special to air on NBC, the network airing the actual Olympics. But when the US opted to boycott the 1980 Summer Games to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the two specials were joined together as a feature.

Lisberger introduced a prototype version of the Tron character (short for “electronic”, natch) in a short promotional animation for his studio that ended up being sold to radio stations around the country. But the story, originally conceived as an animated feature, really began to take shape when computer scientist Alan Kay heard about it and contacted Lisberger to volunteer his services as a consultant. Kay convinced him that the technology existed to use a blend of live-action and computer-generated animation rather than traditional hand-drawn methods.

Lisberger worked on the screenplay with Bonnie MacBird, who had worked in development at Universal prior to joining team Tron. MacBird based the character of Alan Bradley, creator of Tron, on Kay and the couple eventually got married. The hope was to make the film independently but, despite some interest from computer companies like Information International, Inc., Lisberger was unable to secure financing for the ambitious and expensive project.

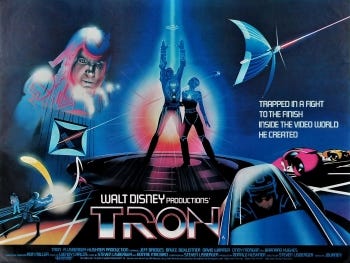

At this point, Lisberger and his producing partner, Donald Kushner, began pitching Tron around Hollywood. The big studios, including Warner Bros. and Columbia, weren’t interested. Eventually, they made it down the list to Disney but even they needed some convincing. At the time, the studio was still reeling from the failure of their last big sci-fi project, The Black Hole. Disney President Ron Miller was not in a hurry to entrust millions of dollars to relative novices on a project utilizing technology that may or may not work. But after Lisberger shot some test footage, Miller was persuaded that it was a risk worth taking and gave Tron the green light.

Historically, Disney had always preferred to develop all their features in house. But an arrangement like this was not entirely without precedent. Around this same time, Miller also hired Michael Nankin and David Wechter to make their teen comedy Midnight Madness. That gamble didn’t exactly pay off, either, and this was certainly on a much bigger scale than Midnight Madness. So it says a lot about Miller’s commitment to revitalizing Disney that he took a chance on Tron.

To design the world of Tron, Lisberger assembled a dream team of conceptual artists. Jean “Moebius” Giraud was already something of a legend in comic book circles thanks to his science fiction and fantasy work published in the French magazine Métal Hurlant and its American translation, Heavy Metal. He had done a smattering of film work, providing concept art and designs for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s never-realized adaptation of Dune and some costume renderings for Ridley Scott’s Alien, but Tron would be his biggest Hollywood assignment to date.

Peter Lloyd was a freelance airbrush illustrator whose futuristic work had graced album covers (for such artists as Kansas and Rod Stewart) and magazines (like Playboy and Psychology Today) throughout the 1970s. His immediately recognizable style is synonymous with the decade. Tron appears to have been his first major film work but he’d continue contributing to Hollywood projects over the next several decades until his death in 2009.

Finally, Syd Mead was one of the most accomplished industrial illustrators of his time. He’d branched into film with Star Trek: The Motion Picture. 1982 was a big year for Mead, with his designs also playing a key role in the success of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. If you were looking to design the future, you couldn’t get much better than these three guys.

With so much riding on the film’s visuals, it would have been easy to treat casting as an afterthought. Fortunately, Lisberger was aware that the audience would need a relatable lead in order to buy in to the heavily stylized computer world they were about to be plummeted into. Casting Jeff Bridges as Kevin Flynn, the wronged software engineer looking for proof that multinational conglomerate ENCOM stole his video game ideas, was an inspired stroke. Bridges had already racked up a pair of Oscar nominations for his work in The Last Picture Show and Thunderbolt And Lightfoot. He was also unafraid to take a chance on an untested director and new filmmaking techniques. Bridges brings an easy charm and energy to Tron that draws viewers in with him. He makes Flynn someone you’d want to hang out and play video games with.

For the dual role of programmer Alan Bradley and his creation, Tron, Lisberger cast Bruce Boxleitner. Boxleitner had only appeared in a couple of features but he’d done a lot of TV, including TV-movies, guest shots and a costarring role on the Western series How The West Was Won. Even though he’s the title role and the hero, Tron isn’t as showy a part as Flynn. But Boxleitner pulls it off, bringing valor and humanity to the role.

Like most of the other roles in Tron, the female lead was split between two characters: Lora, an engineer, current girlfriend of Alan and ex-girlfriend of Flynn, and her computer program doppelganger, Yori. Another relative newcomer, Cindy Morgan, played both. Morgan had done some guest shots on TV and appeared in the 1980 comedy smash Caddyshack. Shortly after Tron, she’d reunite with Boxleitner on the short-lived (and somewhat underrated, in my opinion) adventure series Bring ‘Em Back Alive.

Originally, Lisberger and Kushner pursued Peter O’Toole to play the villainous ENCOM executive Ed Dillinger and Sark, the computer program carrying out the commands of the Master Control Program. But O’Toole couldn’t wrap his head around the project and passed. (To be fair, most of the actors in Tron couldn’t really wrap their heads around it either but they were able to make the leap of faith that O’Toole couldn’t.) Instead, they went with David Warner, a distinguished, classically trained actor who had no compunctions about enthusiastically leaping into popcorn movies. Between his roles in Tron, Time After Time and Time Bandits, Warner came to be the quintessential bad guy for many members of my generation.

Rounding out the cast is Barnard Hughes as Dr. Walter Gibbs, one of the founders of ENCOM, and the guardian program, Dumont. Hughes was a highly respected character actor who’d appeared in everything from Midnight Cowboy to Oh, God! Considering his warm, grandfatherly demeanor and his ubiquitousness as an actor throughout the 1970s, it’s a little surprising we haven’t already encountered him in a Disney feature.

Of course, the real stars of Tron were always destined to be the groundbreaking visuals. On that score, the film did not disappoint. Harrison Ellenshaw, the son of legendary Disney matte painter and visual effects designer Peter Ellenshaw, had followed in his father’s footsteps. In addition to working on such Disney films as Pete’s Dragon, The Black Hole and The Watcher In The Woods, he’d done some moonlighting on movies like Star Wars. Ellenshaw’s contributions to Tron were so vital that he earned an associate producer credit.

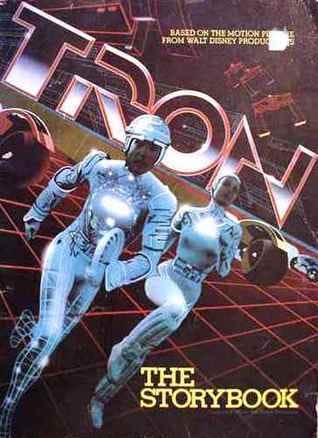

One of the things that makes Tron such an exciting and unique visual experience is the way it blends computer animation, then very much in its infancy, with traditional methods deployed in innovative and ground-breaking ways. The finished film contains only about 15 minutes of fully computer-animated footage, which was still a staggeringly high number back in 1982, produced by several different studios and companies. Considering the piecemeal way the film had to be but together, it’s remarkable how cohesive and fully-developed it looks.

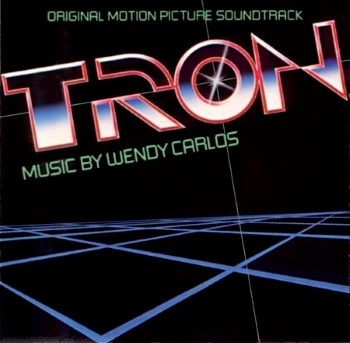

As for the music, Disney had begun casting a wider net over the past decade or so, looking beyond their usual in-house composers and hiring the likes of John Barry (The Black Hole), Henry Mancini (Condorman) and Stanley Myers (The Watcher In The Woods). But those guys were as old-school Disney as the Sherman Brothers compared to Tron’s Wendy Carlos. Carlos was one of the great pioneers of electronic music. Her only previous film experience was about as far removed from Disney as you could get, working with Stanley Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange and The Shining. The Tron score incorporates an orchestra with Carlos’ electronic music, a decision she was reportedly less than thrilled with. But the mix of sounds works in the context of the film, providing an aural equivalent to the film’s blend of computer imagery with live action.

The soundtrack also includes another first for Disney: two original songs by a legitimately popular rock band (unless you count the Beach Boys’ appearance in The Monkey’s Uncle and, if you do, I beg you to reconsider). Journey was coming off the release of Escape, the biggest album of their career, so it’s fair to say that Tron needed Journey a whole lot more than Journey needed Tron. Neither of the new songs became hits but the band’s sound became inextricably tied to the film.

Tron was released to theaters on July 9, 1982, one week after the release of The Secret Of NIMH from Disney defector Don Bluth. Critics were somewhat divided on the film. Siskel and Ebert praised it as the best Disney movie in years and a huge step forward for the art of visual effects. Others couldn’t get past the script, which admittedly somehow manages to be both extremely convoluted and highly simplistic at the same time.

The movie did okay at the box office but Disney had much higher hopes than just okay. In the end, Tron ran into the same problem that plagued every other movie during the summer of ’82: the unstoppable juggernaut of E.T. Families preferred to spend their money on Spielberg’s friendly alien. And sci-fi fans who might be interested in something groundbreaking and new were put off by the Disney name. But even though the studio considered it a disappointment, Tron still pulled in more money than most of their recent efforts.

At the Oscars, Tron earned nominations for Best Costume Design (losing to Gandhi) and Best Sound (where it lost to E.T.). Weirdly, the Academy refused to even nominate the film for Best Visual Effects, arguing that the use of computer animation constituted some kind of a cheat. Had they continued using that rationale, the category would have been retired completely years ago.

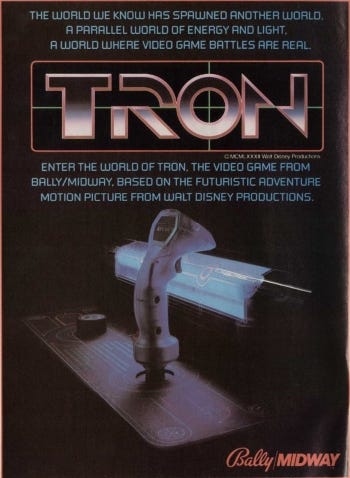

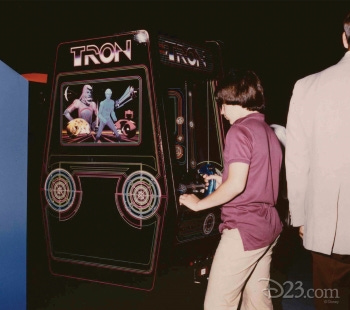

After its initial release, Tron more or less faded from the public consciousness. There were a handful of toys and other ancillary merchandise, plus a couple of arcade games based on the film. I myself happily fed more than my share of quarters into the original, excellent Tron arcade game (that isn’t me in the above picture but it might as well be). But as computers became more sophisticated, Tron began to look quaint and antiquated. The movie definitely had its fans but it was something admitted rarely and with a faint sense of embarrassment.

Eventually, that began to shift a bit. Tron fans started coming out of the closet, enough for Disney to reopen the arcade in 2010 with a sequel this column will get to in due course. But today, even though Tron is appreciated for being ahead of its time, its fans love it because it is very much of its time. The movie has the ability to transport you back to 1982 as quickly and thoroughly as Flynn gets sucked into his computer. It’s not a masterpiece. Even back in ’82, I wasn’t able to make it through without rolling my eyes at some of its hokier moments. But it remains an impressive achievement and a reminder that Walt Disney’s studio was still capable of resurrecting some of its founder’s spirit of innovation and risk.

VERDICT: Disney Plus

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!

END OF LINE

It fills a big screen with so much creativity. It is a classic.