By the end of 1977, every studio in Hollywood wanted their own Star Wars. But unless you were Roger Corman, you couldn’t just crank out a sci-fi epic with intensive visual effects. These things take time, hundreds of artists and technicians and, above all, money. Disney had a bit of a head start. For the last couple of years, they had been quietly developing an outer space project with the uninspiring title Space Station I (later renamed Space Probe One, which isn’t much better). So it’s hardly surprising that the success of Star Wars jumpstarted a project that had been moving in fits and starts. What is surprising is the level of commitment they brought to the table. Producer Ron Miller didn’t just see The Black Hole, as it came to be known, as a chance to capitalize on a hot new trend. He saw it as an opportunity to reinvent the entire way the studio approached live-action production.

Even during its Space Station I days, the movie was always something of a departure for the studio. The original pitch by writers Bob Barbash and Richard Landau was essentially The Poseidon Adventure in space. Disney Legend Winston Hibler was the first producer to take a crack at the project. It was his idea to introduce the threat of a black hole. Hibler worked on the script with Barbash, Landau, and a few other writers but retired at the end of 1975 without producing a satisfactory draft. Still, Hibler kept the door open to return if the studio ever decided to dust it off.

He didn’t have to wait long. In 1976, Miller asked Hibler to give it one more try. Realizing that the visual component of the story was vital to its success, Hibler hired noted space artist Robert McCall to work on concept art. Looking around for a director, he landed upon John Hough, who had recently made Escape To Witch Mountain. Hough was interested but thought the story needed work, so he brought in writers of his own.

Hibler also reached out to the great matte painter and visual effects artist Peter Ellenshaw. Ellenshaw had won an Oscar for his work on Mary Poppins and been nominated twice more, for Bedknobs And Broomsticks and The Island At The Top Of The World. He had also retired but Hibler knew The Black Hole would require the best artists Disney could get. Peter Ellenshaw more than fit the bill.

Sadly, bringing Ellenshaw back into the fold would prove to be Winston Hibler’s last major contribution to The Black Hole. On August 8, 1976, Hibler died at the age of 65. By this point, enough work had been done that putting it back on the shelf would have been unfeasible, so Ron Miller took the reins as producer. John Hough, who was beginning to grow impatient, went off to make Return From Witch Mountain. When that film was done and The Black Hole still wasn’t ready to go, Hough left the project entirely, although he would eventually return to Disney.

While Ellenshaw and his team continued working on the visual side, Miller brought screenwriter Jeb Rosebrook on board for a total rewrite. Like Barbash and Landau, who still received “story by” credit for planting the seed in the first place, Rosebrook worked primarily in television. By this point, everyone had grown disenchanted with the disaster angle (it probably didn’t hurt that the disaster movie cycle of the 1970s had already begun to play itself out). Rosebrook pared the story down, cutting extraneous characters and coming up with a structure that bore more than a passing similarity to Disney’s own 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea.

With Hough out of the picture, Miller approached Gary Nelson, director of Freaky Friday. Nelson passed on the job. Although he thought the preproduction work and concept art looked great, he still didn’t think the script was there. Miller agreed and brought one more writer on board. Gerry Day was another prolific TV writer and the only one with a Disney credit on her resume, having written the two-part Shadow Of Fear for The Wonderful World Of Disney. Day punched up Rosebrook’s script and, after years of development, Disney finally had a workable screenplay.

The blockbuster success of Star Wars had been another reason for Day’s involvement. While Star Wars had been extraordinarily popular with kids, nobody was referring to it as a kids’ film (well, a few snobby cranks were but they were in the minority). If The Black Hole was going to come anywhere near that level of success, it couldn’t be rated G. So for the first time, Ron Miller decided to break a mandate that had been in place at Disney ever since the MPAA began issuing ratings in 1968. The Black Hole would be rated (gasp) PG.

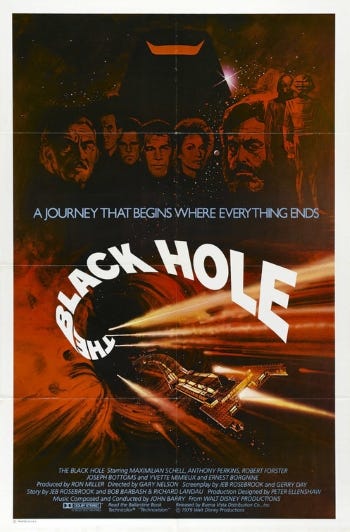

With Nelson officially on board to direct and a script, peppered with a few PG-guaranteeing hells and damns, everyone could at least live with, attention turned to casting. Once again, Miller and Nelson thought outside the box, assembling a group of actors nobody would ever think to associate with Disney. To play Dr. Hans Reinhardt, the obsessed, Captain Nemo-like commander of the USS Cygnus, the long-lost ship perilously perched just beyond the reach of the black hole, they chose Maximilian Schell. Schell was an Austrian actor known for intense performances in movies like The Man In The Glass Booth, Julia and his Oscar-winning turn in Judgment At Nuremberg. With a full beard, thick unkempt hair and wild eyes, Schell is like a more dangerous version of James Mason in 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea.

If Miller and Nelson were looking for actors outside of Disney’s usual wheelhouse, they couldn’t have done much better than Norman Bates. Anthony Perkins was well-cast as Dr. Alex Durant, one of two scientists on board the USS Palomino. Durant becomes a little too interested in Dr. Reinhardt’s research. With Perkins in the role, you’re genuinely uncertain where his loyalties lie right up until the end. It’s hardly surprising that neither Schell nor Perkins ever returned to Disney but they both made it through their one feature with dignity intact.

The other Oscar winner in the cast was Ernest Borgnine as journalist Harry Booth. Considering that Borgnine starred in McHale’s Navy with future Disney stars Joe Flynn and Tim Conway (not to mention the fact that he said yes to a whole lot of questionable movies over the course of his long career), I am a little surprised that this is the first and last time he’ll be in this column. He’s fine in a somewhat inconsistently sketched role. I’ve seen The Black Hole a few times now and either I never realized he was some kind of reporter until this time or I always forget because it’s such a minor aspect to his character. His purpose on board the Palomino seems to simply be Ernest Borgnine. Which is fine, I guess. All deep space missions could stand to have an Ernest Borgnine on board.

The officers in charge of the Palomino, Captain Dan Holland and Lieutenant Charlie Pizer, were played by Robert Forster and Joseph Bottoms. Forster had made his film debut in John Huston’s Reflections In A Golden Eye in 1967. He never quite broke through as a leading man, despite starring in the countercultural masterpiece Medium Cool and two short-lived crime shows of the 70s, Banyon and Nakia. Today, of course, he's remembered as a beloved character actor thanks to a late-career resurgence after Quentin Tarantino directed him to an Oscar nomination in Jackie Brown. But in 1979, his career was in transition between studio work and independent cult stardom. I don’t think anyone expected him to be cast in a Disney movie but I doubt anyone was particularly surprised to see him pop up in one, either.

Joseph Bottoms had been working since the early 70s, winning the Most Promising Male Newcomer Golden Globe for his work in 1974’s The Dove. Since then, his biggest role had been in the hugely popular, critically praised TV miniseries Holocaust. Disney must have felt Bottoms had potential at the studio. He was tapped to host Major Effects, a promotional episode of Disney’s Wonderful World on the making of The Black Hole. Perhaps they pushed him too far with the ridiculous superhero costume he was forced to wear as Major Effects. We won’t be seeing him back in this column.

To play Dr. Kate McCrae, the sole female member of the Palomino’s crew, Disney looked at a number of actresses including Sigourney Weaver. They eventually settled on Jennifer O’Neill, the star of the 1971 coming-of-age hit Summer Of ’42. However, she would have to cut her hair to accommodate filming the zero gravity sequences. O’Neill reportedly wasn’t thrilled with this condition but allowed it, steeling her nerves with wine while Vidal Sassoon himself chopped her hair off. On her way home from the studio, she crashed her car and ended up in the hospital. O’Neill was out.

To replace her, Disney cast the only on-camera actor with previous experience at the studio. Yvette Mimieux had appeared opposite Dean Jones and Maurice Chevalier in the wacky comedy Monkeys, Go Home! back in 1967. She’d kept busy since then on movies and TV, even branching into writing with the 1974 TV-movie Hit Lady (directed by Tracy Keenan Wynn, son of frequent Disney bad guy Keenan Wynn and grandson of frequent Disney goofball Ed Wynn). Mimieux cut her hair without incident and was probably pleased to land a role as a non-sexualized, professional woman.

Despite all the new faces, Miller couldn’t help but hedge his bets with a couple of familiar voices. After C-3PO and R2-D2 became breakout stars, The Black Hole absolutely needed to include some cute and hopefully iconic robots. They came up with V.I.N.CENT (Vital Information Necessary Centralized) and his older, battered counterpart BO.B. (Bio-Sanitation Battalion). To provide the voices for the robotic odd couple, Miller and Nelson tapped Disney veterans Roddy McDowall and Slim Pickens. Both actors went uncredited but you don’t need vocal recognition software to know who it is. This will be the last we see (or hear) from either actor for quite some time. McDowall will eventually deliver one more vocal performance but Slim Pickens passed away on December 8, 1983.

The legacy of The Black Hole is a bit complicated. Budgeted at $20 million, it was the most expensive movie Disney had ever produced (which, these days, seems almost quaint). I’m not a fan of the expression “you can see every dollar on the screen” but in this case, it seems more accurate than not. The movie looks phenomenal with lavish sets, mostly top-notch visual effects and an overall style that had been lacking from virtually every other Disney movie of the last 10-15 years, if not longer.

Even the opening credits are a noticeable departure from the established Disney house style. For decades, actors had been credited alongside the names of the characters they played. The Black Hole throws that out the window, opting instead for traditional credits over a computer-generated grid (the studio’s first extensive use of computer-generated imagery and you can bet we’ll be seeing a whole lot more soon) and John Barry’s phenomenally eerie score. It feels like a real movie, not a Disney movie.

Despite the best efforts of the many writers involved, I don’t think they ever quite got there with the script. As a skeletal framework upon which to display the work of the effects artists, the story does what it needs to do. But you certainly never care about any of the characters or become invested in their dilemma. When Dr. Reinhardt informs Kate that her father, Reinhardt’s partner, died, she doesn’t seem particularly saddened or even surprised. The crew of the Palomino isn’t very tight-knit for a small group of people who’ve been stuck together in space for lord knows how long. Reinhardt has a more intimate relationship with his menacing, blood-red robot Maximilian than any of the humans on board Palomino have with each other.

And for all Miller’s laudable ambitions to try something new and different, the movie can’t help but fall back on some typical Disney conventions, especially with V.I.N.CENT and Old BO.B. The robots’ design emphasizes cuteness over practicality. Audiences had thought R2-D2 was cute but that didn’t feel like cuteness had been the goal. He still felt like a functional droid. V.I.N.CENT and BO.B. look like anthropomorphized floating trash cans, all rounded edges and sensitive but motionless eyes. To be fair, Maximilian also looks pretty impractical. He’s just a single fused hunk of metal. But at least he looked cool in a way the others absolutely did not.

One can’t talk about The Black Hole without discussing its bizarre, semi-ambiguous ending. Obsessed with entering the black hole, Reinhardt pilots the Cygnus into the void while the survivors from the Palomino attempt to escape on his probe ship. Both ships end up entering the black hole in a sequence seemingly inspired by the finale of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Inside, Reinhardt and Maximilian become one, presiding over a barren hellscape, while the Palomino crew is guided by what appears to be an angel through a crystal tunnel and apparently out the other side.

When I first saw The Black Hole back in 1979, my 10-year-old brain didn’t know what to make of this. And not in a good, mind-blown kind of way. More like an I’m-so-confused-what-is-happening-right-now way. Nobody else I knew seemed satisfied by this ending, either. It’s not as though the final sequence is open to a lot of interpretation. Reinhardt and Maximilian go to hell while Holland, Pizer, Kate and V.I.N.CENT go to heaven. But audiences weren’t hungry for a heaping dose of metaphysical weirdness with their sci-fi adventure story. Even today, the final sequence feels either too ambitious for such a slight story or not ambitious enough.

The Black Hole premiered in London on December 18, 1979, opening in the U.S. on December 21, to tremendous fanfare. The studio committed an additional $6 million to marketing their ambitious departure and the film was accompanied by a promotional blitz of toys and tie-ins. It was a disaster. A few critics praised the look of the film but nobody liked the story or the characters.

On the plus side, the film did manage to nab two Oscar nominations. Frank Phillips, a longtime Disney cameraman whose first credit as cinematographer had been Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N. back in 1966, was nominated for Best Cinematography. He lost to Vittorio Storaro for Apocalypse Now. Fair enough. Peter Ellenshaw and his team, including his son Harrison Ellenshaw, Art Cruickshank, Eustace Lycett, Danny Lee and Joe Hale, were recognized for Best Visual Effects. They lost to H.R. Giger, Carlo Rambaldi and the team from Alien. Again, I get it. The Black Hole looked great. Those movies looked better.

Regardless, the public wasn’t all that interest. The toys and comics largely sat unsold. At the box office, it couldn’t compete with another big-budget science fiction release. Star Trek: The Motion Picture had opened a couple of weeks earlier and dominated theatres for most of December, even though its tremendous budget made Paramount view its success as a disappointment.

At the time, Disney would have killed for a disappointment like that. They’d sunk everything into The Black Hole and would end up having to take a loss. Its failure set back Ron Miller’s plans for the studio and forced the studio to take a hard look at where they were headed. It would be a few years before they attempted anything on this scale again.

Today, The Black Hole is very much the product of a studio going through some awkward growing pains. Ron Miller in particular knew that the old Disney was on the verge of extinction. They had been behind the times for an entire generation and their attempt to play catch-up only made things worse. The studio needed to change if it was going to survive. The Black Hole was Disney’s first attempt to move away from the kids’ table to eat with the rest of the grownups. It was a big swing and even though he missed, Miller would have a few more turns at bat.

VERDICT: We’ve been grading on a curve here for awhile now, so I certainly can’t call this a Disney Minus. It’s an A for effort and compared to a lot of other movies we’ve covered lately, it’s a clear Disney Plus. Compared to the rest of the movies that existed in the world of 1979, maybe not so much.

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!

Great review. And I think you hit the nail on the head as to the characters not being likeable. Star Wars and Star Trek both had warm characters who cared about each other and we cared about them. Alien had a crew of people who were well drawn as human beings. Black Hole is impressive in many ways but the end result, at least for me, is why should I care about these people?

Thank you for another wonderful article. I remember watching this on cable in the early 80's and having the ending scare the bejesus out of me!