Disney Plus-Or-Minus: Amy

It’s a bit of an exaggeration to say that Walt Disney had been involved in television from the invention of the medium. However, it’s fair to say that he jumped in the very second people started figuring out how to make money from it. From the beginning, the line between film and television production had been porous. Episodes of Davy Crockett and Zorro were edited together and released to theatres. Loads of TV-movies were released theatrically overseas, where Disney didn’t have a network home. And every so often, a television production would get bumped up to the big leagues and receive a theatrical release in the U.S.

By 1981, this practice had become a lot less common. In the 1950s, Disney’s TV production values were routinely as good as if not better than the average B-movie. This was no longer the case. Other studios could get away with releasing Battlestar Galactica or Buck Rogers In The 25th Century to theatres. If Disney had tried releasing Sultan And The Rock Star or The Secret Of Lost Valley to cinemas, to name just two typical Wonderful World Of Disney entries from the late 70s, they’d have been laughed off the screen.

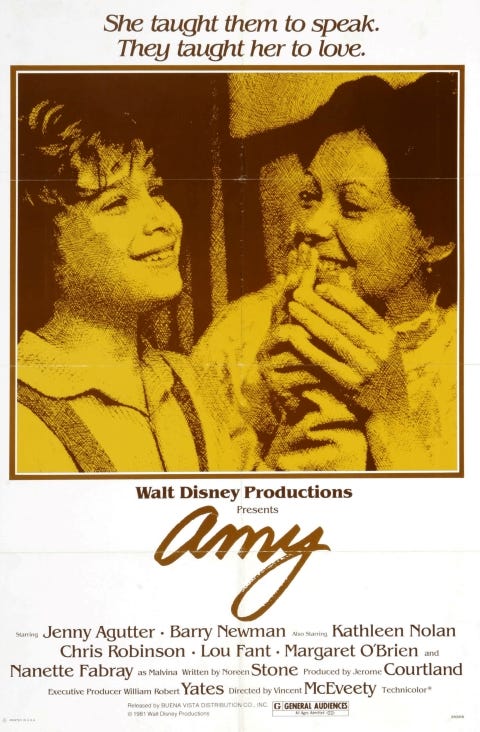

Still, there was always a place for a low-key, character-driven period piece in theatres and Amy, one of the last Disney TV productions to receive a theatrical release, certainly fit that bill. The project was written by Noreen Stone, a Disney newcomer who went on to write soap operas, notably Search For Tomorrow, and the Brooke Shields comic strip adaptation Brenda Starr. Assuming it’s the same Noreen Stone, she’s been teaching screenwriting at UCLA for a number of years now.

This will be the last Disney credit for producer Jerome Courtland and director Vincent McEveety. Courtland had been a Disney actor (Tonka), director (Run, Cougar, Run) and producer (most recently on The Devil And Max Devlin). He continued his career as a director into the ‘90s, helming episodes of night-time soaps like Dynasty, Falcon Crest and Knots Landing. After leaving Hollywood, he taught for awhile before passing away in 2012 at the age of 85.

It will be strange to not have to double-check the spelling of McEveety anymore. Over the last year or so, it seems like hardly a week has gone by without an appearance by Vincent or one of his brothers, Joe and Bernard. Vincent McEveety directed an even dozen Disney features, from The Million Dollar Duck to Treasure Of Matecumbe to Herbie Goes Bananas. His name will pop up once more in this column but Amy was his last full-fledged directing assignment for any studio to receive a theatrical release. He kept busy in television, including a Disney TV-movie in 1986 called Ask Max starring Jeff Cohen (a.k.a. Chunk from The Goonies). McEveety died in 2018 at the age of 88.

The film’s star, British actress Jenny Agutter, wasn’t quite a Disney newcomer. In 1966, a 13-year-old “Jennifer” Agutter appeared as a ballet student in the made-for-TV program Ballerina. Since then, she’d built an impressive filmography in movies like Nicolas Roeg’s classic Walkabout, Logan’s Run and Equus. A few months after Amy was released, she’d costar in John Landis’s An American Werewolf In London, a movie that had a slightly larger cultural impact than her Disney work.

One of the interesting things about Amy is how slowly and methodically it allows its story to unfold. When we first meet Amy Medford, she’s leaving behind a note and boarding a train bound for Appalaichia where she’s starting a new job as a speech teacher at a rural school for deaf and blind children. Plenty of folks at the school are glad to see her, including Superintendent Lyle Ferguson (Lou Fant) and deaf student Henry Watkins (Otto Rechenberg). But some, like fellow teacher Malvina Dodd (Nanette Fabray), think it's a waste of time trying to teach deaf kids to speak. Malvina communicates with sign language and, according to Ferguson, the divide between “manualists” and “oralists” is well-nigh unbreachable.

It isn’t until a bit later that we learn that note was left for Amy’s husband, Elliot (Chris Robinson), a rich Boston businessman. Whatever else Amy may have written in that note, she didn’t leave a forwarding address. So Elliot hires private detective Edgar Wambuck (Lance LeGault) to track down his runaway wife and bring her home.

Meanwhile, Amy (who has received the sign-name Amy-On-The-Lips) has made a couple of friends, despite her ongoing disagreements with Malvina. The town doctor, an occasionally inebriated sawbones named Ben Corcoran (Barry Newman, star of the cult thriller Vanishing Point), finds her attractive and, more importantly, believes in her mission. He begins to spend more time at the school, helping the sick and courting Amy.

She also confides in another teacher, Helen Gibbs (Kathleen Nolan), about her situation back in Boston. She and Elliot had had a child who was hearing impaired. When her son became ill thanks to a heart defect, Elliot essentially gave up on the boy, sending him to a state hospital where he died. Convinced that their son’s health problems were somehow Amy’s fault, Elliot refused to have any more kids with her. That’s when Amy decided to leave him and apply for the teaching job. Despite having no formal teaching experience, a forged letter of recommendation helped secure the position.

Ferguson is asked to welcome a new student, a 19-year-old deaf boy named Mervin Grimes (played by 6’6” Brian Frishman, you may remember him as the unfortunately named Barf in Midnight Madness). Mervin is older than the other students but his parents are insistent that the school is Mervin’s only hope for any sort of education. Thanks in part to his childlike wonder at the world, he soon forms a deep friendship with Henry.

Mervin certainly comes in handy when Amy and Ben take the students for a picnic and see a bunch of other kids playing football. Ben thinks Amy’s kids would benefit from team sports, so he and the school’s handyman, Clyde Pruett (Disney regular Jonathan Daly, last seen in The Shaggy D.A.), teach them the fundamentals. They challenge the other school to a game and surprise everyone with a come-from-behind victory that gets written up in the local papers, alerting Elliot’s detective to Amy’s whereabouts.

While Amy has had some success teaching the kids to read lips and speak, especially Henry, Ferguson discovers her past and confronts her at Christmastime. However, she refuses to resign and insists that she’ll find another post elsewhere if she’s fired. While Ferguson mulls his options, trouble rears up among the students when Mervin hits a bully who’s been making life miserable for Henry. Terrified of getting in trouble, Mervin runs away just as Elliot shows up to take his wife home.

Amy wants nothing more to do with her husband and joins the search for Mervin. The boy has been following the train tracks back home and is tragically struck and killed because he couldn’t hear the train whistle blowing. Mervin’s parents are understandably distraught, more convinced than ever that deaf kids just can’t be taught. But Henry shocks them by pointing to Mervin and saying, “My friend.” The Grimes family is so impressed by this demonstration that they immediately hand over their other deaf child, Mervin’s little sister, Pearl, to the school. Ferguson agrees to forget all about Amy’s past and, her job secure, Amy resolves to stay and leave Elliot for good.

If they gave Academy Awards for good intentions, Amy would have swept the 1981 Oscars. Disney really tried with this one, making a movie that’s wholesome enough for families but mature and progressive in some surprising ways. Unfortunately, while its heart is in the right place, Amy just doesn’t work as a piece of dramatic storytelling. The ingredients are all there, they just needed a completely different kitchen staff to whip them in to something palatable.

Let’s focus on the good stuff first. Noreen Stone’s script isn’t exactly a feminist manifesto but it does create a strong, complex and potentially compelling female character. Elliot never seems physically abusive but he was absolutely emotionally abusive and manipulative. That was not a common reason for women to leave their husbands in 1981, much less 1913 when the story takes place. It’s genuinely surprising to see it in a Disney movie, just as it’s surprising to see a still-married woman take up with a new man.

The movie was also ahead of its time in its depiction of the visually and hearing impaired. Several cast members had personal connections to these communities. Nanette Fabray herself suffered from significant hearing loss and was a longtime activist for the hearing impaired. Lou Fant, the hearing child of two deaf parents, was a sign language expert, a poet, a translator and a teacher. He was one of the founding members of the National Theatre of the Deaf, the internationally renowned performing arts company. Otto Rechenberg, who played Henry, was also deaf and most of his fellow students were cast from the California School for the Deaf.

Of course these days, all of the kids would likely be played by hearing impaired and visually impaired actors. That was not the norm in 1981, so most of those students are relegated to the background. Except for Rechenberg, larger roles were filled with sighted and hearing actors, including Frishman, David Hollander, and Cory “Bumper” Yothers (brother of Family Ties’ Tina Yothers and Return From Witch Mountain’s Poindexter Yothers). Still, McEveety deserves some credit for incorporating as many students from the California School as he does. It would not have been unusual at that time to hire zero deaf actors.

McEveety, Stone and the cast and crew of Amy get so much right that I really wish the movie itself was better. There’s certainly nothing about the film that transcends its television origins and demands a theatrical release. If you stumbled across Amy on the Disney Channel in the ‘90s, you might have mistaken it for a lost episode of Avonlea. Disney certainly knew its way around low-budget period movies by this point. With some generic, old-timey costumes, minimal sets and lots and lots of exteriors, it was pretty easy to recreate 1913 on the cheap.

The performances are OK but nothing special. Agutter seems distant and removed from a role that seems like it should be highly emotional. That’s certainly a choice but it makes it difficult for the audience to invest in Amy’s journey. The entire cast is earnest and committed but that’s about it. There’s almost a sense that they’re performing volunteer work rather than giving actual performances. It doesn’t help that Stone’s script arguably bites off more than it can handle and ends up handling most of its dramatic beats in the most abrupt, unsatisfying way possible. The Grimes’ climactic transition from “you killed our boy” to “you’re a miracle worker, here, take our daughter” is only the most glaring example.

Amy’s credit sequences also include an original song: “So Many Ways” by Disney veteran Robert F. Brunner and Bruce Belland, the lyricist responsible for such tunes as “The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes”, “The Boatniks” and “He’s Gonna Make It” from The Barefoot Executive. It isn’t much of a song and I only mention it because the singer is none other than Julie Budd, who we just saw in The Devil And Max Devlin. If Disney had you on the lot or in the studio for one project, you can bet they were going to try to squeeze another out while they had you.

Amy made its way into select theatres on March 20, 1981, just a couple of weeks after The Devil And Max Devlin. To improve its chances, the studio booked it in many theatres alongside a re-release of Alice In Wonderland. They also pushed a captioned version for hearing impaired audiences, another innovation that was far from commonplace in ’81. But Amy couldn’t compete with Damian. The Final Conflict, the third Omen movie, easily won the box office.

About a year later, Disney’s educational division released a condensed version of the film, retitled Amy-On-The-Lips, to schools. This was, perhaps, a better, more natural fit for the film. Even in its full-length version, Amy often feels like an extended public service announcement. Cutting it down to about half an hour for middle schoolers just makes sense.

Today, Amy occupies a weird place in Disney’s library. Its only DVD release to date has been as part of the Disney Generations Collection of MOD titles, home of such obscurities as The Waltz King and Fuzzbucket. And yet, it’s readily available on Disney+, so it’s not as though the studio is trying to bury it. Perhaps they’re trying to gauge interest in a potential remake. If done correctly, that is not a terrible idea. Amy has a lot of potential that was left largely unrealized in 1981. That’s exactly the kind of movie Disney should be remaking.

VERDICT: It’s a Disney Plus for effort, a reluctant Disney Minus for execution.

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!