Disney entered 1981 as a studio with a severe identity crisis. Longtime producer and Walt’s son-in-law Ron Miller took over as president in 1980. He had been instrumental in Disney’s first tentative steps toward a slightly more adult image, releasing PG-rated fare like The Black Hole and Midnight Madness, even though the Disney brand was kept off the latter for fear of alienating their base. At the same time, Miller maintained the status quo with more traditional, G-rated films such as Herbie Goes Bananas. So far, nothing had helped to rehabilitate Disney’s image as a studio on the decline.

They had even entered a limited partnership with another studio, Paramount, to coproduce two features. The first of those projects, Robert Altman’s Popeye, had been released domestically by Paramount in December of 1980 (Disney retained the international distribution rights). Popeye actually made money but the response was so negative that it was widely viewed as a massive flop. Nevertheless, Popeye still outgrossed every other Disney release in 1980 even though, at least in America, it was considered a Paramount picture. When your biggest hit of the year is a critical bomb that half belongs to another studio, it might be time to reconsider your strategy.

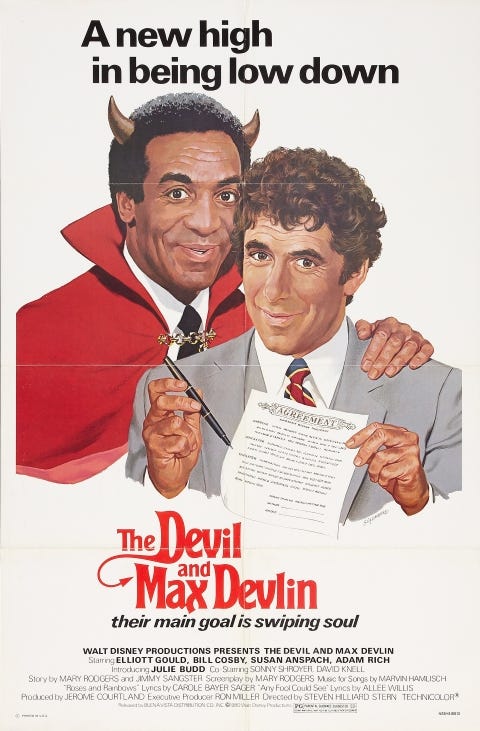

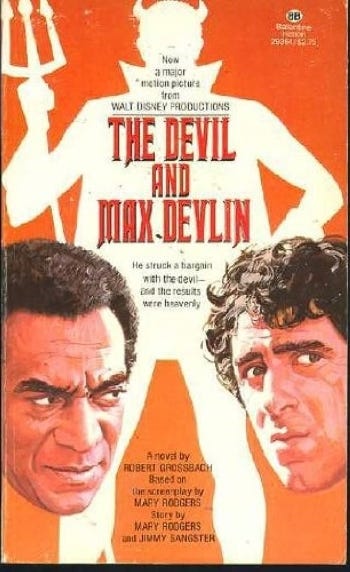

Disney’s first release of 1981, The Devil And Max Devlin, was another flirtation with PG-rated fare not specifically geared toward a kiddie audience. The project began as a script called The Fairytale Man by prolific Hammer Films screenwriter Jimmy Sangster. Sangster originally conceived the project as a horror vehicle for Vincent Price, who would have played an out-of-work actor collecting the souls of children for the Devil. Unfortunately, this was in 1973 when Hammer was struggling to stay afloat. The studio was unable to secure financing for The Fairytale Man, which is a shame because I, for one, would have been all over that movie.

I’m not quite sure how the project ended up at Disney. When it did, it’s hardly surprising that Ron Miller decided it needed a rewrite. He hired Mary Rodgers, who had distinguished herself with Freaky Friday, one of the few bright spots in Disney’s 1970s filmography. She changed just about everything from Sangster’s script, including the title. Sangster would later distance himself from the finished film, although he had no trouble cashing Disney’s check.

The director, Steven Hilliard Stern, was new to Disney. He’d directed a few theatrical films and a whole lot of television, both episodic and TV-movies. TV would continue to be his primary focus for the rest of his career. In 1982, he’d direct one of Tom Hanks’ weirdest early movies, the Dungeons & Dragons-inspired thriller Mazes & Monsters. He’d return to Disney in 1986 to direct the TV-movie Young Again, starring Robert Urich as a middle-aged businessman who gets his wish to be 17 again. The teenaged Urich was played by a young actor named K.C. Reeves, although you may know him better as Keanu. If nothing else, Stern certainly worked with some interesting people.

The Devil And Max Devlin was no exception. Max was played by Elliott Gould, about as far as you could get from Vincent Price. This would be Gould’s second and last Disney film following The Last Flight Of Noah’s Ark. His stint at Disney hadn’t added much luster to his stardom. He’d make it through the 1980s with a handful of lower-profile movies and TV appearances. Eventually, of course, he’d transition to supporting roles in movies like Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s series. This might be his last appearance in this column but he’s still very much in demand as a character actor, so he could still pop up somewhere down the road.

On the other hand, I feel confident that Gould’s Devil And Max Devlin costar will absolutely not be appearing in any future Disney projects. It’s difficult to discuss Bill Cosby these days without considering the multiple allegations of sexual assault made against him. But The Devil And Max Devlin is less challenging in that regard than, say, The Cosby Show. Sure, it might be tough to still see Cosby as America’s favorite sitcom dad. But it’s now considerably easier to buy him as the Devil’s right-hand man.

Cosby had been approached by Disney before but he’d always turned them down, having heard that the studio wasn’t a very welcoming place to African-Americans. I don’t know specifically which movies he’d been offered but considering that you can pretty much count on one hand the number of Disney movies we’ve covered so far with significant roles for Black actors, he may have had a point. But The Devil And Max Devlin was different. The role appealed to Cosby precisely because Satanic characters were usually played by white guys. So even though his wife had serious reservations about him playing a demon (either she knew something the rest of us didn’t or she absolutely did not), Cosby finally agreed to star in a Disney picture.

It's also important to keep in mind that in 1981, Bill Cosby wasn’t exactly on top of the world. His last TV series, the sketch comedy show Cos, had been a short-lived flop in 1976. He hadn’t appeared in a movie since California Suite in 1978. Fat Albert continued to air on Saturday mornings but he was arguably best known at the time for pitching Coca-Cola and Jell-O Pudding Pops. Cosby was in no position to be overly picky.

Gould’s Max Devlin isn’t all that different from Noah Dugan in The Last Flight Of Noah’s Ark. Max and Noah are both slightly seedy characters who favor cheap cigars and easy money. Max runs a rundown “apartment house” in L.A., dodging his tenants’ complaints and doing as little work as possible. He is literally dodging some of his more persistent tenants when he accidentally steps out in front of a bus and is killed, sending him straight to H-E-Double-Hockey-Sticks.

Actually, the movie doesn’t employ cutsie euphemisms for Hell. The script is liberally sprinkled with the most profanity (albeit the mildest possible variety) the studio had yet deployed, ensuring a PG rating. That rating and the film’s Satanic overtones would get the studio in hot water with conservative family audiences. Considering some of the movies that have come out under the Disney umbrella since (remember when the studio owned Miramax?), it’s downright quaint to think that people were up in arms over a few “hells” and “damns”.

Max arrives in a suitably fire-and-brimstoned Hell that includes some repurposed stock footage from The Black Hole. He’s welcomed by a committee of demons presided over by The Chairman (Reggie Nalder, who’d recently played the vampire Kurt Barlow in the TV version of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot). After hearing a litany of the misdeeds that landed him in Hell, souls manager Barney Satin (Cosby) offers him a deal. If Max can convince three innocents to sign their souls over to the Devil in three months, he can go free. If not, an eternity of torture and damnation awaits.

Barney assigns Max three targets: aspiring singer-songwriter Stella Summers (Julie Budd, a nightclub singer in one of her only film appearances), high school dweeb Nelson “Nerd” Nordlinger (David Knell, whose eclectic post-Disney career includes appearances in the T&A comedy Spring Break, Troma’s Chopper Chicks In Zombietown and the Nicolas Cage drama Pig) and a young boy named Toby Hart (Eight Is Enough’s Adam Rich, fulfilling his destiny as a child star of the 1970s by appearing in at least one Disney movie). Max also gets the use of a very limited set of magical powers to help make their dreams come true because, let’s face it, who’s going to sell their soul to Elliott Gould without at least a little magic.

First up is Stella, whose dream is fairly straightforward. Max first runs into her in a local club having an open mic night (they meet in the ladies’ room since Max doesn’t quite have the hang of the whole teleportation thing yet). Unfortunately, her crippling stage fright renders her incapable of singing a note on key. But Max’s magic kicks in as long as he’s within eyesight of his target. Under his watchful eye, she wows the crowd with a rendition of “Any Fool Could See”, one of two original songs composed for the film by Marvin Hamlisch (his first Disney gig since The World’s Greatest Athlete).

Record executive Jerry Nadler (Chuck Shamata) catches Stella’s performance and is so impressed he immediately signs her to a record deal. Of course, Stella can only sing if Max is watching, so Max becomes her manager. Not surprisingly, he turns out to be more successful at managing talent than apartments. Stella’s record quickly rockets to the top of the charts, her tour sells out and she wins a Grammy. No doubt if Max had another few days, she’d have pulled an EGOT hat trick.

Nerd Nordlinger also has quasi-show-business-related aspirations. He wants to be a champion motocross racer. Only trouble is that he has absolutely no idea how to ride a motorcycle. So Max poses as the owner and operator of Max’s Mobile Motocross School. Just like with Stella, as long as Max can see him, Nordlinger rides like a champ. On his first ride, he impresses his idol, Big Billy Hunniker (Sonny Shroyer, who had appeared on a couple episodes of The Wonderful World Of Disney but was then best known as Enos on The Dukes Of Hazzard). Big Billy invites the kid to his next race and, again just like with Stella, Nerd swiftly carves out a rep as the best motocrosser to ever cross a moto. His classmates are so impressed that they change his nickname from “Nerd” to “Nerve”.

Toby’s dreams are a whole lot more complicated. He lives with his widowed mom, Penny (Susan Anspach, who had recently worked with director Steven Hilliard Stern on the drama Running, co-starring former Disney star Michael Douglas). Penny makes ends meet running a daycare out of her home and Toby’s wish is for her to find happiness with a new man. All the kids at the daycare love Max but Penny is understandably suspicious of some rando her son found trolling a carnival looking for kids. She agrees to go out with him after he has brand-new playground equipment installed in her backyard. I’m not sure that particular gesture would make me feel any better about Max’s motives but hey, I’m not here to judge.

Despite everyone’s success, Max still has trouble getting people to sign on the dotted line, much to the aggravation of Barney Satin. After a whirlwind courtship, Penny agrees to marry Max and Barney begins to put the pressure on. Max finally gets Stella, Nerve and Toby to sign the contracts. But the moment they do, they turn on Max, becoming selfish egomaniacs without a shred of decency.

Max realizes that he’s been had. Despite Barney’s promise that his victims would be allowed to live out the rest of their natural lives before he came to collect their souls, he figures out that payment will be due much, much sooner. Max’s conscience gets the better of him and he burns the contracts, even though a now-fully-demonic Barney threatens him with eternal torture in the deepest pits of Hell. As soon as he does, an angel appears to save Nerve’s life. Stella thanks Max for giving her the confidence to believe in herself. And Penny and Toby, who really did fall in love with Max somehow, welcome him to the family. In the end, everyone gets together at Stella’s concert to enjoy her new single, “Roses And Rainbows” (with lyrics by no less than Carole Bayer Sager!).

It probably goes without saying that The Devil And Max Devlin is not a particularly good movie. It sets up a bunch of rules surrounding Max’s powers and assignment, then either forgets all about them or ignores them completely. Like a vampire, Max does not cast a reflection in a mirror after his return from Hell. You’d think this would be a noticeable handicap but nobody ever comments on it. Max’s strict deadline is also a bit of a joke. Stella’s meteoric rise to the top should have landed her in the Guinness Book under World’s Fastest Overnight Success.

Elliott Gould, having apparently noticed that nobody at Disney seemed to care that he was giving less than one hundred percent in The Last Flight Of Noah’s Ark, gives a similarly disinterested performance here. You can practically see him glancing at his watch, waiting for the end of the day. But because he’s Elliott Gould, he still gets away with some fun moments.

Bill Cosby, on the other hand, actually uses this opportunity to play against type. Apart from a few moments during a party sequence where he mugs it up while dancing, this is a very un-Cosby-like performance. That’s not necessarily a great thing. To give the devil his due (pun very much intended), Cosby was a brilliant standup and effective in roles that utilized his low-key charm, like his breakout role on I Spy. Here, he dials down the charm and replaces it with…well, nothing, really. Barney Satin should be the most charming MF-er in the world. Instead, he’s just kind of a blank slate. Cosby comes to life in the few moments at the end when he’s all decked out in full demon prosthetics and that brief sequence is admittedly kind of cool. But it would have had a lot more impact if we’d had something more interesting to contrast it with.

After it was done filming, Ron Miller appeared to lose faith in The Devil And Max Devlin. It was bumped from its prime Christmas release slot to February 6, 1981. Audiences and critics alike hated it, although Gene Siskel actually gave it a positive review and praised Disney for taking chances. This was particularly surprising since Siskel had been responsible for some of Disney’s most vitriolic negative reviews over the past decade.

As mentioned earlier, the film also generated some controversy among those who wanted Disney to remain the home of squeaky clean G-rated family films. Across the pond, its video release caused a stir when a guy named Liam Sanford hilariously trolled the British censorship committee, demanding it be added to the list of banned “video nasties” alongside titles like Cannibal Holocaust and Faces Of Death. The movie was briefly pulled from circulation, proving Sanford’s point that nobody was really bothering to watch these movies and that the hysteria was overblown to the point of absurdity.

Considering the movie’s lack of popularity and Cosby’s current persona non grata status, it’s hardly a shock that Disney has quietly swept The Devil And Max Devlin under the rug. But the film’s failure and the complaints it generated further cemented Ron Miller’s belief that Disney needed another outlet for projects that didn’t fit the studio’s stereotypical image. It would be another couple of years before he’d figure out how to solve that problem. But eventually he did and the studio would never be the same.

VERDICT: I’d sell my soul to get these 95 minutes back, so obviously it’s a Disney Minus.

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!

I am sad the Price movie doesn't exist. It would have kicked ass even if only for Vincent Price being in it.