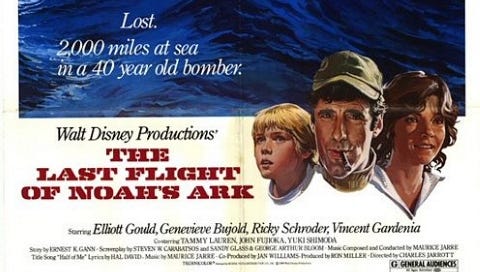

By 1980, Disney was finally starting to take a few chances. Some of these gambles were pretty big, like The Black Hole. Others were small, such as taking a chance on new talent and an unfamiliar genre in Midnight Madness. But the studio wasn’t averse to falling back on old favorites. Case in point: the castaway movie. Disney had gone back to this well a few times with wildly varying results. Swiss Family Robinson had been a huge hit and was a lot of fun. Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N. and The Castaway Cowboy had been neither of those things. Still, it had been a few years since the studio had underwritten a trip to Hawaii, so producer Ron Miller decided it was time to roll the dice on another one with The Last Flight Of Noah’s Ark.

The film was based on the short story “The Gremlin’s Castle” by aviator and sailor Ernest K. Gann, author of acclaimed aviation-themed novels like Fate Is The Hunter and The High And The Mighty. The screenplay was credited to three writers new to the studio: Steven W. Carabatsos, who had worked on Star Trek, Sandy Glass, and George Arthur Bloom. Bloom also came from TV, where he had been a comedy writer for a number of shows and worked with Disney veterans Don Knotts and Julie Andrews. He later segued into animation, although not for Disney. He’d go on to write for the likes of My Little Pony, Transformers and The Magic School Bus.

In an interview with The Los Angeles Times, Miller claimed he had deliberately sought out writers, actors and a director who had not worked with Disney before. He can perhaps be forgiven for forgetting that Charles Jarrott had, in fact, already directed The Littlest Horse Thieves for the studio just a few years earlier. Evidently that movie had made as little impression on the folks who made it as it had on audiences.

Miller was correct that the cast, apart from a couple of familiar faces in bit roles, was new to the studio. About ten years earlier, Elliott Gould had been one of the biggest stars in the country thanks to movies like Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice and Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H. But he’d hit a rough patch in recent years with movies like Harry And Walter Go To New York and the boxing kangaroo embarrassment Matilda flopping hard at the box office. His career had hit the stage where signing a two-picture deal at Disney actually made sense. Gould will be back in this column before long.

Canadian actress Geneviève Bujold had worked with Charles Jarrott before, earning an Oscar nomination for her performance in Anne Of The Thousand Days. Since then, she had bounced between Hollywood and Canada, most recently appearing in the popular thriller Coma and Bob Clark’s Murder By Decree, a cult hit, especially in Canada, pitting Sherlock Holmes against Jack the Ripper. Bujold didn’t really need Disney and we won’t see her in this column again, but she probably felt she owed Jarrott a solid for kickstarting her career.

Miller also tapped a couple of new child actors, one of whom was on the cusp of stardom. Ricky Schroder had just made his film debut in the 1979 remake of The Champ when he was cast in The Last Flight Of Noah’s Ark. Critics savaged The Champ but audiences flocked to it. Schroder became the youngest ever recipient of the Golden Globe for Best New Male Star of the Year. Two years after Noah’s Ark, he began starring on the sitcom Silver Spoons. His TV gig kept him busy enough that he didn’t return to Disney and these days, he’s more likely to make headlines for yelling at Costco employees over mask mandates or his other far-right views, so he won’t be back in this column.

Schroder’s costar, Tammy Lauren, also appeared in a lot of television throughout the 80s. She made one more Disney project, the 1987 TV production Bride Of Boogedy. Horror fans might recognize her from the 1997 movie Wishmaster. In 1992, Charles Jarrott became her stepfather after Jarrott married her mother, Suzanne. It’s a small world, after all.

Gould stars as Noah Dugan, a down-on-his-luck pilot with a mountain of gambling debts owed to mobsters Benchley and Coslaugh (Dana Elcar and John P. Ryan). Desperate for a job, any job, Dugan visits Stoney (Vincent Gardenia), the owner of a dilapidated old airfield. As it happens, Stoney has a job for him. The only trouble is that it’s a job nobody in their right mind would want to take.

Stoney’s client is a missionary named Bernadette Lafleur (Bujold). She and a gaggle of orphan volunteers, including Bobby (Schroder) and Julie (Lauren), have been raising pigs, chickens, ducks, a cow and assorted other livestock for a remote island community in the South Pacific. Stoney has agreed to fly her and the animals out to the island but his original pilot took one look at the cargo and the beat-up old B-29 he’s expected to fly and bailed.

At first, Dugan is convinced the first pilot had the right idea. But when Benchley and Coslaugh turn up at the airfield looking for him, he changes his tune and starts loading up the plane. Dugan doesn’t bother hiding his dislike of the animals, prompting Bobby to grow concerned for their welfare. He impulsively decides to stow away on board the aircraft as it’s prepping for takeoff with Julie hot on his heels.

Dugan and Bernadette take an immediate dislike to each other. Dugan annoys her with his incessant cigar smoking and by calling her “Bernie”. She bugs him playing classical music from a portable cassette player and with her naïve piety. The music gets them in trouble after she hangs the tape player too close to the controls and it messes up the compass. Off-course and running out of fuel, Bobby spots an island on the horizon big enough for Dugan to perform an emergency landing.

The castaways quickly discover they are not alone on the island. A pair of Japanese soldiers, Hiro (Yuki Shimoda) and “Cleveland” (John Fujioka), have been stranded there for decades, completely unaware that World War II is long over. Dugan recommends keeping a safe distance between themselves and their potential enemies. But Bernie rejects this advice. She seeks them out almost immediately, winning them over despite the language barrier and sharing a meal with them. Before you know it, the two groups are one big happy family.

Of course, there are still some points of contention. At first, Dugan is perfectly content to bide his time and wait to be rescued. He reconsiders his position when Cleveland points out that if it was that easy, he and Hiro wouldn’t still be stuck there after thirty-plus years. He next proposes building a raft but Hiro and Cleveland have another idea. If they can flip the plane over, they can use the tail as a rudder and put together a makeshift sailing vessel. With nothing to lose and plenty of time on their hands, they decide to give it a shot.

Romance begins to blossom between Dugan and Bernie while they’re modifying the plane. But Bobby still doesn’t trust him, especially after Dugan suggests abandoning the animals on the island, fearing that all the extra weight will drag the plane straight to the bottom of the ocean. It doesn’t take long for Dugan to ease up on his anti-animal agenda and consent to bringing the menagerie along for the ride.

Finally, the newly rechristened Noah’s Ark is ready to set sail. Hiro and Cleveland nearly miss the launch after they take too long setting explosives to destroy all their remaining supplies, obeying decades-old orders set by the Japanese Emperor. With nothing left to go back to, Dugan and crew have no choice but to pin all their hopes on Noah’s Ark.

Bringing the animals helps a little bit, since they’re able to stretch their dwindling food supplies with eggs and milk from the cow (Hiro and Cleveland also had a seemingly endless cache of rice mercifully unspoiled by the ravages of time). But the animals also need to be fed and even after the cow stops giving milk and the chickens stop laying eggs, Bobby and Julie refuse to even consider eating one of their friends. So Bernie releases one of the ducks, hoping it will act as the Biblical Noah’s dove and find land or rescue.

Meanwhile, Bobby suggests using the lights to attract fish since Hiro and Cleveland haven’t had any luck fishing during the day. Bobby’s idea works a little too well, attracting a great white shark (and if you ever doubted how thoroughly Jaws had permeated pop culture in the 1970s, the appearance of a shark in a Disney film should dispel any confusion). Bobby accidentally falls overboard and Dugan dives in to save him, erasing any remaining bad blood between the two.

Between random shark attacks and a big storm, things are looking bleak for the Noah’s Ark crew. The situation gets worse when Bobby’s beloved bull takes sick. This time, even Bernie agrees that the merciful thing would be to put the poor beast out of its misery. Hiro even has a gun ready to walk Bobby through this difficult rite of passage. But the kid is saved from having to go full Old Yeller by the horn of a passing Coast Guard ship. The duck came through after all! The captain marries Dugan and Bernie on the spot. And don’t worry, kids. Jarrott makes sure to cut back to Noah’s Ark where the official Coast Guard Veterinarian has managed to pull the bull back from the brink of death. And so, we take our leave of Noah’s Ark with the truly terrible theme song, “Half Of Me”, playing for what feels like the millionth time.

It would be nice to report that The Last Flight Of Noah’s Ark represented a nadir for Walt Disney Productions and that things got better from here. But as we’ll see in the weeks ahead, things could and did get even worse than this big nothing of a movie. This is the kind of movie Disney could throw together in their sleep and it appears that’s exactly how they went about making it. Not a single person seems remotely engaged with this material.

Any time there’s a whiff of potential conflict, it either lands with a soft thud or is promptly disposed of. Dugan’s gambling debts that set the wheels of the plot in motion are completely forgotten the moment the plane is in the air. The oil-and-water relationship between Dugan and Bernie turns to puppy love so quickly, you’ll think a scene or two went missing. Both the kids and the animals disappear frequently, only trotted out when absolutely necessary.

And then there’s the business with Hiro and Cleveland, two more regrettable caricatures in the long line of Disney stereotypes. I suppose the best one can say about them is they could have (and likely would have) been so much worse if the movie had been made 15-20 years earlier. But now, Bernie smooths things over with them so quickly that there’s really no benefit to making them forgotten World War II soldiers at all. They’re just a couple of guys who know how to turn a bomber into a boat.

The Last Flight Of Noah’s Ark was released June 25, 1980, and most critics absolutely hated it. At the box office, it represented another column of red ink in Disney’s ledger. It certainly didn’t help that most of the tickets sold were either discounted children’s prices or half of a drive-in double feature alongside a re-release of One Hundred And One Dalmatians. The studio was in desperate need of a hit and this very much was not it.

VERDICT: Disney Minus.

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!

I remember seeing this one at the Kenwood Drive-In in Louisville, KY, but have no memory of 101 DALMATIANS being the second feature. I have no doubt that you’re right, but that movie has never made much of an impression on me….