Unless you’re Trey Parker and Matt Stone, animation takes a long time to produce. That’s certainly always been the case at Disney. It was not uncommon for the studio to take years developing and producing their animated classics. One benefit of this system is that everyone involved in the making of the film has a clear vision of the movie they’re trying to make. Once it’s done, it’s usually done, without much need for extensive post-production tinkering. At least, that’s how it’s supposed to work. In the case of Disney’s notoriously troubled 1985 fantasy The Black Cauldron, the system fell apart.

The Black Cauldron is based on a series of five young adult fantasy novels (a pentalogy, if you will) called The Chronicles Of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander. The first, The Book Of Three, was published in 1964 and the last, The High King, came out in 1968. Alexander’s books were inspired by his interest in Welsh mythology, which means that spell-check is going to have a field day with the names in this one. The High King was awarded the prestigious Newbery Medal, one of the highest honors in children’s literature.

Disney acquired the rights to The Chronicles Of Prydain in 1971 at the urging of legendary animators Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas. These days, Disney would probably approach this material with an eye toward making five movies (or, even more likely, a Disney+ streaming series). But that was not how people thought back in the 1970s, definitely not at Disney. Even Ralph Bakshi tried to cram as much of The Lord Of The Rings as possible into one film. So Disney set to work dismantling The Chronicles Of Prydain and trying to make a single movie out of its parts.

Eventually, the very large development crew decided to focus on the first two books, The Book Of Three and The Black Cauldron, plucking ideas and characters from each and occasionally tossing in material from the later books. Animator John Musker was originally chosen to direct the project and Rosemary Anne Sisson, whose Disney credits include Candleshoe and The Watcher In The Woods was hired to write the script. But Sisson was used to writing, you know, screenplays. She didn’t fare well under the Disney animation method of having a story department come up with ideas for sequences they’d like to animate which would then have to be stitched together. Sisson ended up leaving the project and Musker himself was reassigned after most of his ideas were shot down.

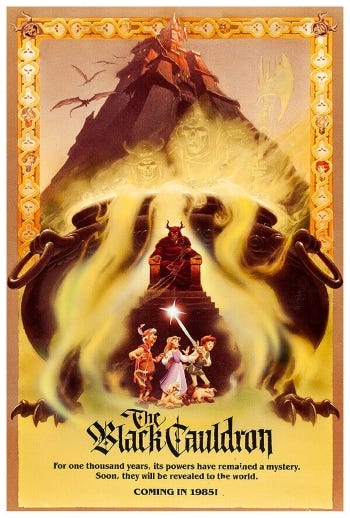

With Musker gone, work continued under the direction of Art Stevens, Dave Michener, Ted Berman and Richard Rich. It was beginning to seem like sooner or later every single person on the Burbank lot was going to be involved in this movie and none of them could agree on a direction. Finally, Disney president Ron Miller stepped in and put Berman and Rich, who had just wrapped up The Fox And The Hound, in control. The studio targeted a Christmas 1984 release date.

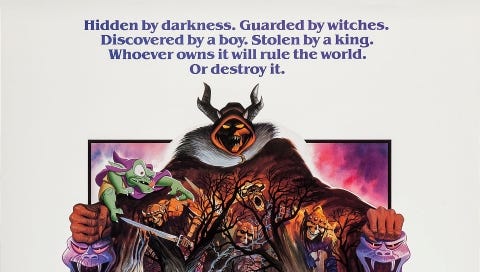

The movie focuses on Taran (voiced by Grant Bardsley), the young Assistant Pig-Keeper to Dallben (Freddie Jones, best known for his role as the cruel circus owner Bytes in David Lynch’s The Elephant Man). Dallben is the protector of Hen Wen, an adorable pig with the mystical ability to produce visions in a pool of water. Hen’s existence has been discovered by the evil Horned King (John Hurt, who was offered the role while working on Disney’s live-action Night Crossing). The Horned King seeks the Black Cauldron, a source of great power that would enable him to raise an Army of the Dead and destroy the world. So Dallben tasks Taran with taking Hen Wen to a remote cabin and keeping her safe from the Horned King at all costs.

Taran proves to be remarkably ill-suited to this job, losing track of Hen Wen almost immediately while fantasizing about being a great warrior. While trying to track her down, he encounters Gurgi (John Byner), a small, furry thing and professional irritant with an insatiable appetite for “munchies and crunchies”. Taran can’t seem to rid himself of this pest until he spots Hen being pursued and carried away by two of the Horned King’s dragon-like Gwythaints. When Taran resolves to sneak into the Horned King’s castle and rescue Hen Wen, the cowardly Gurgi temporarily takes a powder.

He manages to gain entrance to the castle but can’t keep his presence a secret for long, loudly crashing into the Horned King’s throne room. The Horned King forces Taran to demonstrate Hen Wen’s powers but the boy disrupts the spell before she can reveal the location of the Black Cauldron. Taran is able to get Hen Wen to safety but is captured before he can escape himself and thrown in the dungeon.

Taran isn’t stuck in the dungeon for long. Another prisoner, Princess Eilonwy (Susan Sheridan), pops into Taran’s cell in her efforts to find an escape route. Exploring the castle, Taran helps himself to a magic sword from the late king’s burial chamber. They also meet another prisoner, the wandering minstrel Fflewddur Fflam (voiced by Nigel Hawthorne and you see what I mean about these names). The pair free Fflewddur and make their escape with the help of Taran’s new sword.

Freed of the castle, the little group reunites with Gurgi, who has picked up Hen Wen’s tracks. They soon fall into a whirlpool that transports them to the realm of the Fair-Folk, led by King Eidilleg (Arthur Malet, last seen in a small role in Bedknobs And Broomsticks). The Fair-Folk have been protecting the pig and Taran has the idea to find the Cauldron first and destroy it. Turns out, the king knows exactly where it is. He assigns ornery handyman Doli (Byner again) to be their guide and transports them to the Marshes of Morva.

There, they find the Cauldron is in the possession of three witches (voiced by Eda Reiss Merin, Adele Malis-Morey and Billie Hayes, a.k.a. Witchiepoo on H.R. Pufnstuf). Taran agrees to trade the sword for the Cauldron. But once the deal is struck, the witches reveal that the Cauldron is essentially indestructible. The only way to stop it is for somebody to climb inside of their own free will and sacrifice themselves. Needless to say, no one jumps at the opportunity to volunteer for the suicide mission.

Making matters worse, the Horned King has been keeping tabs on them and now sends his followers to recapture them (everyone except Gurgi, that is, who panics and runs away again). The Horned King uses the Black Cauldron to raise his Army of the Dead and sends them out into the world to wreak havoc. Fortunately, Gurgi has finally grown a spine and turns up to rescue his friends. Taran intends to jump into the Cauldron but instead, Gurgi delivers a fairly depressing speech for a Disney movie about how nobody likes him and he has nothing to live for and he leaps in. The Army is defeated and the Horned King is torn to shreds by the Black Cauldron.

The three witches return, intending to take back the Cauldron. Taran proposes another trade, the Cauldron for Gurgi. At first, it appears that they’ve made another witches’ bargain and simply delivered Gurgi’s lifeless corpse. But no, Gurgi comes back to life and the restored group of adventurers heads for home.

The Black Cauldron was nearly finished when Berman and Rich received some unwelcome news. Ron Miller had been fired and replaced by Michael Eisner and his new head of production, Jeffrey Katzenberg. Eisner and Katzenberg were not originally fans of the animation division and considered eliminating it altogether. Instead, they kicked them out of their longtime Burbank home and sent them to a new, much cheaper facility (basically a warehouse) in Glendale.

Katzenberg in particular hated The Black Cauldron. A disastrous test screening that had children terrified by the dark fantasy gave him all the ammunition he needed to put the film on hold. Katzenberg, who at the time knew nothing about animation, demanded significant changes be made. After someone explained that cartoons don’t work that way, it’s not like they had a bunch of unused footage sitting around and they’d have to start from scratch, Katzenberg started making cuts in an attempt to lighten the film’s tone. This was not easy. After all, the film’s darkness had been intentionally built into its DNA from the start. This was always intended to be a departure from Disney’s usual style. In the end, Katzenberg succeeded in cutting about 10 minutes from the film, particularly from the climactic Army of the Dead sequence, but the movie still ended up with the studio’s first PG rating on an animated film.

The Black Cauldron was finally released on July 24, 1985. It was a disaster. The movie opened in fourth place, behind National Lampoon’s European Vacation, Back To The Future (which had already been in theatres for a month) and a re-release of E.T. It had been the studio’s most expensive animated feature to date, costing north of $40 million. It struggled to earn back even half that amount. Most critics didn’t care for it, either, although Roger Ebert gave it a thumbs up. I encourage you to track down the episode of At The Movies featuring Siskel and Ebert’s review, which is full of classic Gene and Roger sniping at each other.

It would be nice to report that The Black Cauldron is a neglected gem in the Disney vault. Nice but inaccurate. Despite some truly impressive sequences and Disney’s first, tentative use of computer animation to enhance the visuals, the movie as a whole simply doesn’t work. The characters are difficult to care about, especially Taran, who comes across as a less talented and more self-centered version of Wart from The Sword In The Stone. The Horned King is a great character design in search of a more compelling character. He doesn’t do much apart from loom menacingly and his evil plot is stopped before his army makes it more than a couple of feet out of the castle.

To be fair, while Katzenberg’s cuts certainly didn’t help matters, it’s unlikely that The Black Cauldron would have worked anyway. The characters are too passive and the story lacks clarity and urgency. It’s one instance where Disney’s traditional method of story development failed them. It’s as though everyone involved in the film was so busy trying to define what the movie was not that they never bothered to figure out what it is.

The movie is even more disappointing as an adaptation of The Chronicles Of Prydain. I’d been a fan of Alexander’s books and was genuinely excited to see The Black Cauldron when it came out. Unfortunately, the film doesn’t bear much resemblance to Alexander’s epic fantasy. Everything feels smaller and less consequential, which is not something you should be able to say about a movie with an army of resurrected skeletal warriors.

The failure of The Black Cauldron would have significant consequences for Disney animation. To his credit, Jeffrey Katzenberg realized how little he knew about animation and dove into the studio’s rich legacy. Rather than shutting the division down, he came to believe that animation should be the cornerstone of Disney’s success. But to get there, he’d make some sweeping and dramatic changes to the way Disney made those films. He was not going to let something like The Black Cauldron happen again. We’ll get to the fruits of those labors eventually but they’re still a ways down the road. That’s one thing about animation Jeffrey Katzenberg couldn’t change: it takes a long time.

VERDICT: It’s a Disney Minus with scattered individual moments of Disney Plus-itude.

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!

I wanted so badly to see this at the theater when I was nine. My brother wanted Pee Wee's Big Adventure. Since we couldn't agree, we saw neither. It was a loooooong time before I got to see it, and Pee Wee Herman had been everywhere in that time. I considered myself the bigger loser.