As we discussed last time, the formation of Touchstone Films (later Pictures) in 1984 was a game-changer for Walt Disney Studios. Splash had given the studio its biggest box-office hit in years, as well as some of its best reviews. But while on the face of it, Touchstone may have appeared to be about protecting the good name of Walt Disney, allowing the studio to dip its toes into more adult-oriented entertainment, it was also an attempt to give the Disney name itself a bit of rehabilitation.

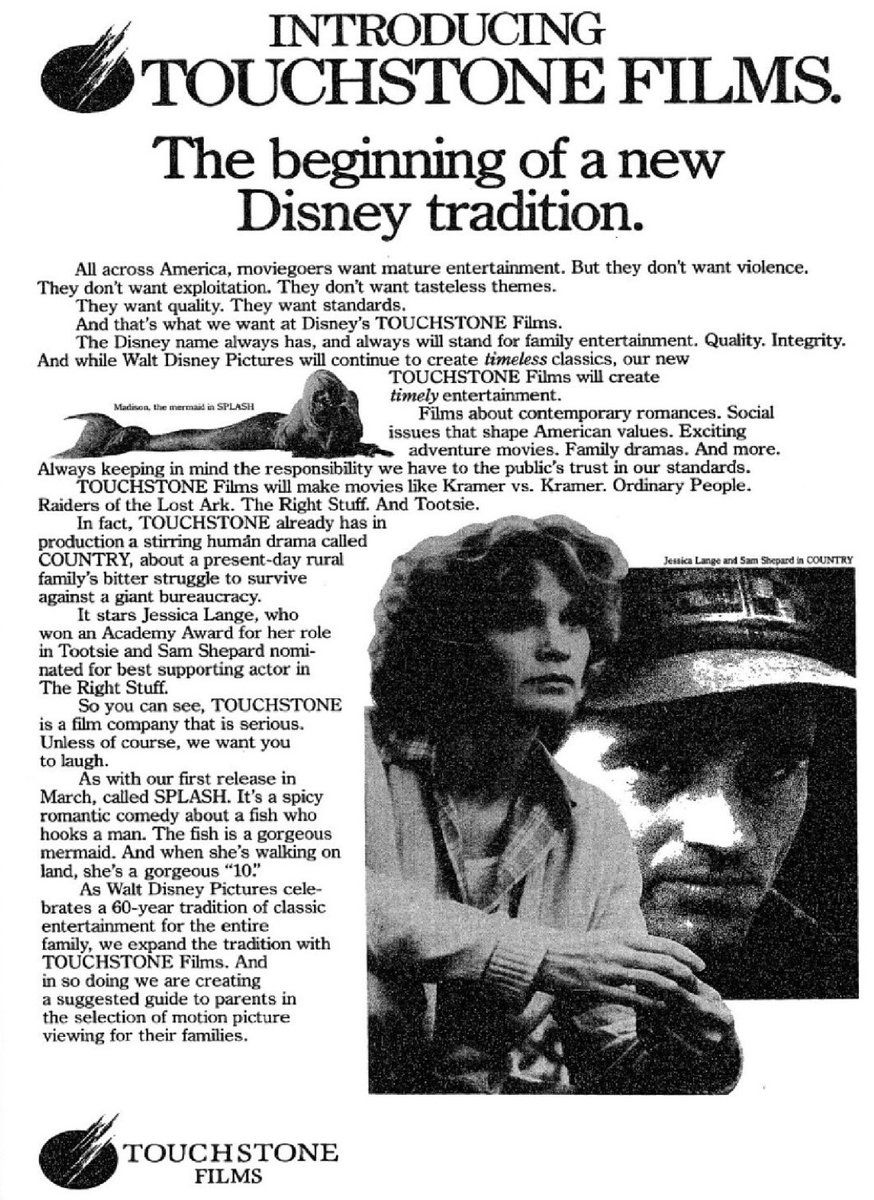

In the past, the studio had released a few movies, such as Midnight Madness and Trenchcoat, where they felt the Disney name would do more harm than good. In those instances, the studio simply kept its name off completely to hide the Disney connection. That was not the case with Touchstone. They very much wanted the public to be aware that Touchstone was an extension of Disney, going so far as to take out full-page ads trumpeting Touchstone as “the beginning of a new Disney tradition."

There’s no denying that the Disney brand was in dire need of an extreme makeover at this time. The studio had earned a not-entirely-unfair reputation for producing wholesome stinkers. They’d occasionally take a big swing with something like The Black Hole or Tron but they seemed incapable of hitting a home run. Most of the time they couldn’t even get a runner on base.

So while the studio switched its focus in 1984 to Touchstone with Splash and Country, Disney retrenched and re-released some of its animated classics. The idea, presumably, was to remind the public of what Disney did best, while at the same time introducing the radical idea that maybe, just maybe, Disney could be cool, too.

When the Walt Disney name was finally ready to be attached to a new movie again, the obvious choice would have been a brand-new animated feature. Indeed, the studio had an extremely ambitious animated film that had been years in the making they hoped to release for Christmas 1984. But The Black Cauldron was a notoriously troubled production and when test screenings suggested the film was much too dark for kids, it was sent back to the editing room and delayed until the following summer.

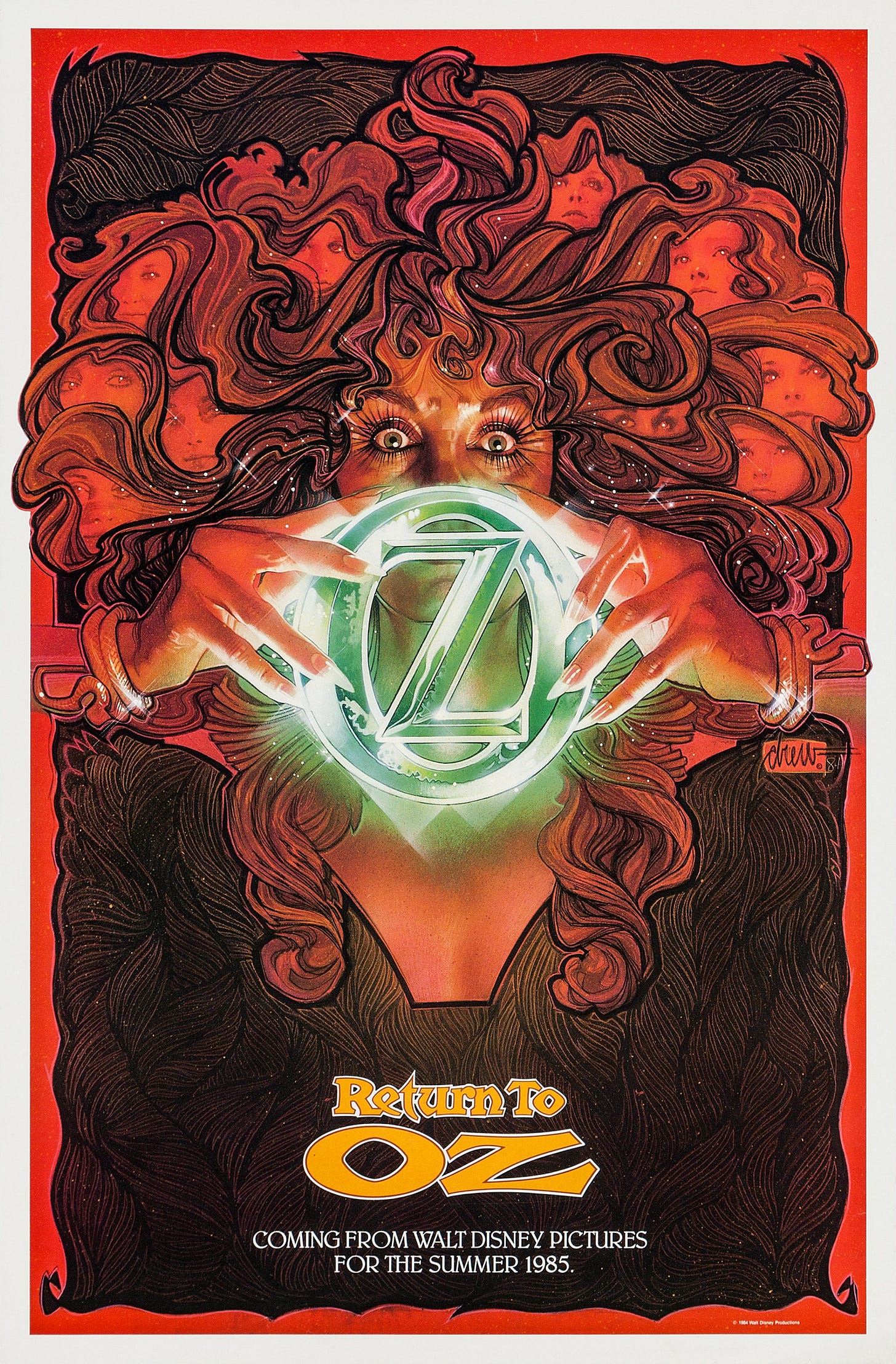

Ironically, this meant that the first new Disney film to hit theatres in over a year ended up being a live-action film with an equally troubled production that was, if anything, even creepier and more disturbing than the animated movie they’d temporarily shelved. Ask any 80s kid who saw Return To Oz during their formative years. This movie is powered by hi-octane nightmare fuel.

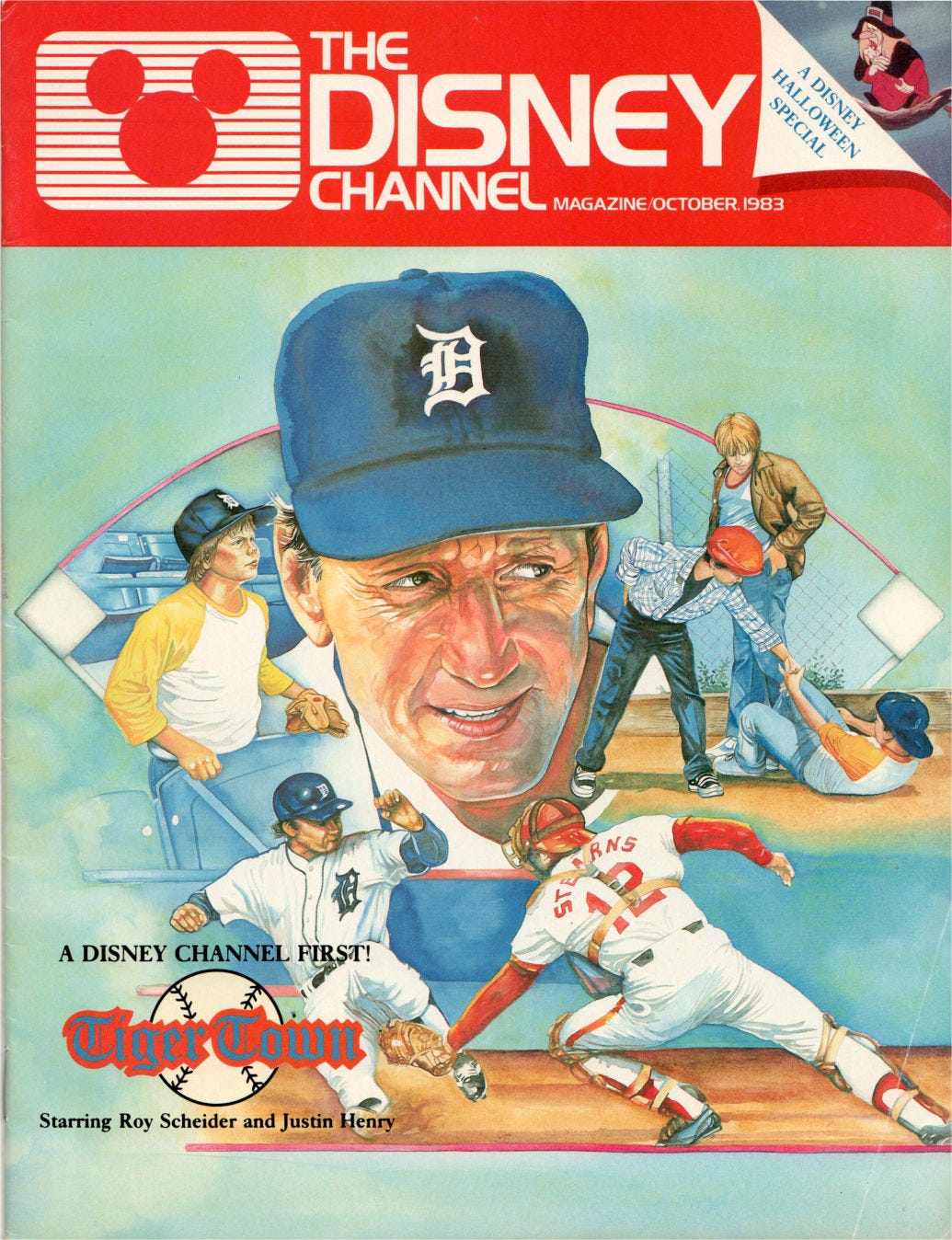

I should mention that calling Return To Oz the first new Disney movie to hit theatres since Never Cry Wolf comes with a bit of an asterisk. On October 9, 1983, the Disney Channel premiered its first original film, the inspirational baseball drama Tiger Town starring Roy Scheider and Justin Henry. In June of 1984, Tiger Town got a very limited theatrical release in Detroit, where the film had been shot and took place. The Deroit Tigers went on to win the World Series that year, so maybe it helped. Anyway, I didn’t live in Detroit in 1984 and I don’t assume too many of you did, either, so I’m classifying Tiger Town as a TV-movie. Apologies to any Michiganders who were looking forward to that one.

There’s one other movie worth bringing up briefly: Touchstone’s third release, Baby: Secret Of The Lost Legend, released on March 22, 1985. I don’t know the whole history of this film (shockingly, a definitive book or documentary on the making of Baby does not seem to exist) but it feels very much like a movie that started out as a Disney production, then got uncomfortably shoved over to Touchstone in an attempt to beef up that slate. It would later have some of its rough edges sanded down and air on The Magical World Of Disney under the title Dinosaur: Secret Of The Lost Legend. I’m not sure Baby even has enough of a following to qualify as a cult movie. Today, it’s sort of a dim Gen-X memory and an example of the growing pains Disney experienced while trying to operate two separate and distinct studios.

Disney’s road to Oz can be traced all the way back to the 1930s, when Walt considered making an animated feature based on L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz as a follow-up to Snow White. Unfortunately for him, he was a little too late. The rights had already been sold to Samuel Goldwyn, who would soon transfer them to MGM.

Walt’s original unrealized Oz project remains one of cinema’s most intriguing what-if scenarios. On the one hand, there’s little doubt that the Disney animators could have made a spectacular-looking Oz movie. But then again, Walt stuck a whole lot of irons in the fire in the wake of Snow White and the late 30s and early 40s were a tumultuous time at the studio. It’s possible that Disney’s Oz would have meant sacrificing Pinocchio or Bambi. Or the project could have been back-burnered until the 1950s or even indefinitely. The only certainty is that a Disney Oz would have erased the classic 1939 film The Wizard Of Oz from the history books. All things considered, things probably worked out for the best.

Oz dropped off Walt’s radar until 1954 when he learned he could acquire the rights to all thirteen of Baum’s other Oz books. Even back then, Disney was never one to acquire just one property when they could snatch up an entire universe in one fell swoop. Walt set to work developing a live-action musical to be titled The Rainbow Road To Oz. We touched on it briefly when we discussed the 1961 movie Babes In Toyland. No one could quite crack the code on the project. After airing an extremely scaled-back version on the fourth-anniversary episode of Disneyland in 1957, The Rainbow Road To Oz was cancelled.

For the next couple of decades, Disney relegated their Oz projects to audio. These would often tiptoe right up to the edge of the 1939 movie. The first release from Disneyland Records was 1965’s The Story Of The Scarecrow Of Oz featuring Ray Bolger himself reprising his role from the MGM film. In 1969, some of the songs written for The Rainbow Road To Oz were repurposed and re-recorded for The Story And Songs Of The Cowardly Lion Of Oz. That same year brought The Story And Songs Of The Wizard Of Oz, which actually licensed the songs from the 1939 movie including “Over The Rainbow”. Finally in 1970, Disneyland Records put the spotlight on the last member of the Big Three with The Story And Songs Of The Tin Woodman Of Oz.

Apart from these records, Oz remained a dead project at the studio until the early 1980s when the studio invited Walter Murch to a pitch meeting. Even if you don’t know Murch’s name, you’re definitely familiar with his work. Murch was a USC graduate who had worked extensively with George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola as an editor and sound designer on such films as THX-1138, American Graffiti, The Conversation and The Godfather films. He had recently won his first Oscar for his pioneering sound work on Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Ironically, his phone stopped ringing after the win, as filmmakers and studios wrongly assumed they could no longer afford his services. In need of a gig and curious about why Disney, of all studios, would possibly want to talk to him, Murch took the meeting.

At the time, Disney was actively recruiting new blood in their never-ending quest to produce their own Star Wars. Murch had worked on the screenplay for The Black Stallion, another movie whose success had filled Disney with jealousy. They’d poached that film’s director, Carroll Ballard, for Never Cry Wolf. And while Murch hadn’t worked on Star Wars, his association with George Lucas at least made him Star Wars-adjacent.

When asked what sort of a project he might like to direct for the studio, Murch pitched the idea of a sequel to The Wizard Of Oz. It seems odd to pitch a studio on a sequel to a movie they hadn’t made and it seems odder still when you consider that Murch had no idea that Disney had the rights to Baum’s other books. As it happened, those rights were about to expire, so the studio was very interested in this idea. Murch went off to write a screenplay with Gill Dennis that combined Baum’s second and third books, The Marvelous Land Of Oz and Ozma Of Oz. It was a bit darker than the studio was expecting but Disney gave Murch the greenlight, although not without some trepidation.

Things got off to a rocky start. Murch and his team were deep into pre-production when Disney hired a new head of production. The new regime was skeptical of the project’s ballooning budget and temporarily pulled the plug unless Murch agreed to rewrite the script and bring costs down. Murch scaled things back and was finally allowed to begin shooting.

Nothing got any easier once the cameras started rolling. Murch ran into countless difficulties and quickly ran behind schedule. Unhappy with the results, Disney fired cinematographer Freddie Francis and, soon thereafter, Murch himself. For a minute, the studio seemed ready to walk away from the whole thing. Murch was rehired a few days later, however, after his old friend George Lucas flew to London to intervene on his behalf. Lucas persuaded the studio to give Murch another shot with his personal guarantee that, if the studio continued to be unhappy with Murch’s work, Lucas himself would step in to finish the picture.

Armed with a new cinematographer (David Watkin) and some sage advice from George Lucas, Murch was able to get the film back on track. But just as things were wrapping up, Disney had another management shake-up. The Michael Eisner/Jeffrey Katzenberg regime had zero interest in Return To Oz. On the plus side, this meant that Murch was able to finish his movie with little to no interference from the studio. But this also meant that the studio didn’t really care what happened to it. Return To Oz was left to sink or swim on its own.

Needless to say, it sank and it isn’t hard to understand why. Return To Oz is a deeply strange movie, which is, of course, exactly why I love it so much. Judy Garland had been a teenager when she stepped into Dorothy Gale’s ruby slippers but Murch stayed true to the books and cast 9-year-old Fairuza Balk in her big-screen debut. That switch makes the film’s creepiness hit a lot closer to home for its intended audience, as well as their parents. But it also creates a disorienting disconnect between it and the film it’s ostensibly a sequel to.

Balk’s Dorothy has a rough go of it even before she leaves Kansas. Fed up with her tales of Oz, Aunt Em (Piper Laurie, dialing back her performance as the crazy mother of Stephen King’s Carrie just a smidge) and Uncle Henry (Matt Clark) ship her off to a clinic where electroshock therapy will hopefully cure her of her delusions. Another girl (Emma Ridley) helps her escape in the middle of a torrential storm. The pair are swept into a flooding river and, while Dorothy loses track of the mystery girl, she comes to in a ravaged Oz. Toto stays in Kansas this time but she’s accompanied by a hen named Billina, who finds she can speak English in Oz. I guess that skill only applies to chickens, not dogs.

In this new, post-apocalyptic Oz, all of the Emerald City’s citizens have been turned to stone, the city’s emeralds have been stolen, the Scarecrow, Oz’s king, has been taken prisoner by the Nome King, and the city is patrolled by roving bands of Wheelers. The Wheelers, who have wheels instead of hands and feet, look like something out of a Mad Max movie directed by Tim Burton. If forced to choose between Wheelers and Flying Monkeys, I’d take the monkeys any day of the week. They seem a lot saner than the Wheelers.

Of course, it wouldn’t be Oz without a witch and Dorothy is soon captured by Princess Mombi (Jean Marsh, who had some prior Disney experience in the 1961 TV production The Horsemasters). In addition to controlling the Wheelers and holding the good Princess Ozma captive (and who turns out to be the mystery girl who helped Dorothy escape), Mombi is known for her large collection of detachable heads. She decides to lock Dorothy up until she grows up enough for her to add her head to her display case.

Besides Billina, Dorothy’s allies include Tik-Tok, a wind-up robot voiced by Sean Barrett, Jack Pumpkinhead, whose name kind of says it all and is voiced by Brian Henson (Jim’s son and someone who will be back in this column eventually) and The Gump. The Gump is an unholy creation made of two sofas lashed together, a stuffed moose-like head, palm-frond wings and a broomstick tail reanimated by the Powder of Life. The Gump is voiced by Lyle Conway and was primarily performed by effects artist Steve Norrington, who went on to direct Blade and The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

Dorothy and her friends eventually wind up in the hall of the Nome King (Nicol Williamson). A great deal of the Nome King sequences was done in Claymation by Will Vinton Studios, whose short film, Closed Mondays, had won an Oscar a decade earlier, beating out Disney’s Winnie The Pooh And Tigger Too. This wasn’t the first time Disney had looked outside of their own Burbank lot to produce animation. Steven Lisberger, the director of Tron, had undertaken the first proof-of-concept work for that film at his own independent studio. But Return To Oz was certainly the biggest job that Disney had outsourced to that point. Vinton and the rest of the effects team were rewarded with an Oscar nomination for their work.

Return To Oz was released on June 21, 1985. To say that critics were not kind is putting it mildly. Gene Siskel wanted it on record that, when he died, he could have had two additional hours that he’d instead wasted on Return To Oz. On its opening weekend, the movie placed a distant 7th at the box office, behind Cocoon, Rambo: First Blood Part II, The Goonies, Lifeforce, Fletch and Prizzi’s Honor. Most of these had already been out for a couple weeks or more. Nobody liked this movie.

At least, not at the time. The movie definitely made an impression on the few kids whose unsuspecting parents took them to see it. For the most part, they were terrified. But, believe it or not, kids actually like to be scared. The movie stayed with them and, in the fullness of time, it built up a cult following. Personally, I came to Return To Oz a bit late. I didn’t see it theatrically, even though I’d read most of Baum’s Oz books. I was probably in my 20s when I finally saw Return To Oz for the first time. I expected a disaster. Instead, I found a flawed but fascinating movie that still managed to freak me out a little bit.

Walter Murch never directed another feature but he seems to be OK with that. He went on to win two more Oscars for The English Patient and direct an episode of the animated Star Wars: The Clone Wars. He also worked with his friends Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas on the Disney theme parks ride/short film Captain EO, which I would love to shoehorn into this column somehow but really just doesn’t fit.

The failure of Return To Oz didn’t seem to affect Disney all that much. The place was under new management and this was a remnant of the past that needed to be wiped away. The studio dumped it and forgot about it. But they had a lot riding on their next movie. Its success or failure would determine a lot about which direction the studio would take.

VERDICT: For me, it’s definitely a Disney Plus. Your mileage may vary.

Please do cover CAPTAIN EO. I would love a rundown of that.