From time to time, this column has had to wrestle with the eternal riddle, “When is a Disney movie not a Disney movie?” One of the earliest examples of this came in 1959 when Roy Disney ignored his brother Walt’s wishes and picked up the rights to the religious epic The Big Fisherman, distributing the film through Buena Vista without the Disney name. In the early 1980s, Disney teamed up with Paramount to cofinance the movies Popeye and Dragonslayer. While Disney distributed the films internationally, here in North America both movies were released by Paramount.

In each of these cases, I regrettably decided that they were not Disney enough to be included in this column. But The Brave Little Toaster is different. To be clear, this is NOT a Disney movie. Ask anyone who worked on it and they will make that abundantly clear. If I had skipped it entirely, I don’t believe anyone would have noticed or cared. However, the movie’s roots are so deeply intertwined with Disney that it takes a fair amount of digging to figure out what separates the two.

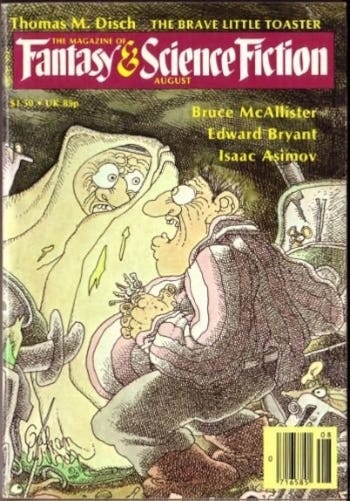

The Brave Little Toaster was originally a short novella by the prolific science fiction/horror writer and poet Thomas M. Disch that appeared in the August 1980 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. The story caught the attention of John Lasseter, one of the recent CalArts grads hired by Disney to bolster their animation ranks. Lasseter lobbied Tom Wilhite, then Disney’s Vice President in Charge of Production, to acquire the rights to Disch’s novella.

Lasseter envisioned an ambitious feature combining hand-drawn character animation with computer-generated backgrounds. To see if the process would even work, he took it upon himself to create a couple minutes of test footage based on Maurice Sendak’s Where The Wild Things Are. Pleased with the results, he pressed forward with his pitch for The Brave Little Toaster, not realizing that his zeal to kickstart his own projects hadn’t exactly made him any friends among the studio’s old guard.

When asked how much money the studio would save utilizing this innovative technique, Lasseter candidly replied somewhere in the neighborhood of zero dollars. At the time, no one could quite wrap their minds around the concept of computer animation as an artistic choice instead of a shortcut. Since Lasseter’s concept wasn’t going to save Disney any time or money, the project was shot down. Not long after, he was fired. It took a while to recover from the sting of losing his dream job but needless to say, we have not seen the last of John Lasseter in this column.

That could have been the end of the road for The Brave Little Toaster if not for The Great Disney Management Shakeup of 1984. As Michael Eisner, Frank Wells and Jeffrey Katzenberg were getting ready to set up shop, Tom Wilhite was deciding it was time to leave. Along with Willard Carroll, Wilhite founded Hyperion Pictures and here’s where things get confusing. Disney has used the name Hyperion on a number of projects over the years, perhaps most notably as a division of their publishing subsidiary, as an homage to the street address of the original Disney studio in Los Angeles’ Silver Lake neighborhood. But Wilhite’s Hyperion Pictures was not and is not a division of Disney. There just happens to be a lot of shared DNA between the two.

At any rate, as Wilhite was packing up his things at Disney, he asked soon-to-be-ex-president Ron Miller if he could hang on to The Brave Little Toaster. Since the only other person at the studio who had been enthusiastic about the project had already been fired, this was not a huge ask. Lasseter had been working on the project with Joe Ranft and Brian McEntee, two more CalArts grads who were increasingly frustrated at Disney. With John Lasseter now up in Northern California at Lucasfilm, Wilhite brought Ranft and McEntee over to continue their work.

In need of a director, Wilhite brought the idea to Jerry Rees, another CalArts alumnus who’d worked on The Fox And The Hound as well as the computer effects in Tron. After Tron, Rees left Disney to try to make it on his own. When Wilhite called, he’d been working with former classmate Brad Bird on an animated feature based on Will Eisner’s classic comic The Spirit. If I could magically will just one unmade movie project into existence, that might be the one. At any rate, they weren’t having much luck with The Spirit, so Rees accepted Wilhite’s offer.

Rees had trouble finding actors to bring his characters to life. Auditions with established voice actors went poorly, with everyone sounding too stilted and cartoony. At the time, Joe Ranft was taking classes with the famed Los Angeles improv troupe The Groundlings. He invited Rees to sit in on a few sessions. There, Rees found almost his entire cast, including Jon Lovitz, Phil Hartman, Tim Stack and Deanna Oliver. Oliver proved to be a somewhat controversial choice for the toaster, with at least one crew member angrily protesting that the character was male. I’m going to assume that crew member did not go on to work on The Simpsons, otherwise their brain would have exploded.

Casting Jon Lovitz as the radio also nearly threw a wrench into the production after he was cast on the eleventh season of Saturday Night Live (Hartman would join him there the following year). Lovitz delayed his departure for New York to accommodate the film and wound up recording his entire part in a single all-night marathon. The session did not, however, leave enough time to record any of the songs. Rees himself did his best Lovitz impersonation (which isn’t half bad) to record Radio’s singing voice.

The film’s oldest and youngest cast members did not come from the Groundlings. Thurl Ravenscroft, who played Kirby the vacuum cleaner, is a voice that needs no introduction. His iconic voice had been featured in a host of Disney films and theme park attractions going back as far as Pinocchio. He’d also performed the song “You’re A Mean One, Mr. Grinch” for Chuck Jones’ How The Grinch Stole Christmas, provided the voice of Tony the Tiger, and generally become one of the quintessential “I know that voice” performers of the 20th century.

The expressive voice of Blanky was provided by 8-year-old Timothy E. Day. Dubbed “One-Take Timmy” by Rees for his preternatural ability to immediately capture the essence of the performance, Day didn’t stay in the business long. He had a handful of credits, primarily on TV, before and after the release of The Brave Little Toaster. But apparently he decided to do other things with his life besides acting.

As an independent production, Wilhite had to cobble together funding from a variety of sources. These included the Japanese electronics company TDK and The Kushner-Locke Company, whose cofounder, Donald Kushner, had dabbled in animation with Animalympics and been a producer on Tron. Wilhite also got some cash by signing a distribution deal with the Disney Channel. His old company remained hands-off during the production of the film but this arrangement would come back to cause some problems later. The movie ended up with a budget of around $2 million, a fraction of what Disney typically spent on an animated feature. To stretch their dollars, Rees, Ranft and McEntee would live for six months in Taiwan overseeing the animation.

In the years since its release, The Brave Little Toaster has become a beloved cult classic among children of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. For those of you who haven’t seen it (a group that, until recently, included me), the story follows the adventures of five household appliances: Toaster, Radio, Kirby the vacuum cleaner, a desk lamp called Lampy, and Blanky, an electric blanket. They live in a seemingly abandoned cottage where they remain optimistic that their Young Master will someday return. When a “For Sale” sign appears in front of the cottage, they decide to take matters in their own…well, not hands, I guess…plugs, maybe? They rig up a desk chair with a car battery and a power strip and head out into the great unknown, heading for the city in search of the Master.

Along the way, the dynamic devices have to battle the elements, a mildly fanatical repairman named Elmo St. Peters (voiced by Joe Ranft), and the existential fear that they might be obsolete. Unbeknownst to them, the Master (whose name is Rob) has grown up and is packing up for college. He still needs a few things, like, conveniently, a toaster, a lamp, a radio, a vacuum and an electric blanket, so he heads out to the cottage with his girlfriend, Chris. When he finds the place in disarray (thanks primarily to the appliances’ attempts to figure out travel arrangements) and the items gone, he takes it pretty hard.

As for the machines themselves, after escaping Elmo’s clutches, they make their way to the Master’s ultra-modern apartment. They’re reunited with an old friend from the cottage, a black-and-white TV (voiced by Jonathan Benair) in Rob’s room. But the new electronics are not happy to meet the old crew. They toss them into the trash to be carted off to the junkyard. Fortunately, the TV is able to steer Rob and Chris in that direction by airing some fake commercials. They arrive just as our heroes seem destined for the trash compactor.

Watching The Brave Little Toaster for the first time in 2024, it’s impossible to not see the film as something of a dry run for several of the movies from Pixar’s first few years. Toy Story and its first couple of sequels are clear descendants but you can also see hints of Cars and WALL-E in there. But in 1987, no one had seen anything quite like this. Animated movies routinely anthropomorphized animals. Heck, it was virtually the backbone of the medium. But turning inanimate objects into fully developed characters with emotions and inner lives was something new.

It was that inner turmoil that likely imprinted itself on the generation that first discovered The Brave Little Toaster. Their fears and dread are brought vividly to life through some intensely animated sequences that would have probably been vetoed at Disney. Toaster’s utterly bizarre clown dream is an obvious example but there are plenty more. Elmo’s shop with its Frankensteined gadgets and Peter Lorre-inspired lamp (voiced by Phil Hartman, who also plays the cottage’s Jack Nicholson-esque air conditioner) is another standout, as is the relentless electromagnet’s pursuit of clinically depressed cars at the junkyard.

These memorable showstoppers also benefit from the original songs by Van Dyke Parks. Disney was still a few years away from recapturing their musical magic. Movies like The Fox And The Hound and The Great Mouse Detective still had a few songs but they weren’t exactly hip. Van Dyke Parks, on the other hand, had had a very eclectic career, both with his own music and collaborating with artists like Brian Wilson, Harry Nilsson, Ry Cooder and countless others. Interestingly, his very first professional job had been with songwriter Terry Gilkyson, arranging his song “The Bare Necessities” for The Jungle Book. Parks’ four songs are miles away from the pleasant but forgettable tunes Disney had been churning out. It’s also worth noting that only one, “City Of Light”, could remotely be described as upbeat or optimistic. The others, especially “It’s A B-Movie” and “Worthless”, tap into intensely negative feelings.

All that being said, there is a reason that The Brave Little Toaster is a cult movie and something like Toy Story is universally beloved. The movie does tap into a universal feeling of needing to feel wanted, useful and necessary. And there’s something powerful behind the idea that the things we use imprint themselves on us and vice versa. The Toy Story movies beautifully capture that bond between kids and their toys. But there’s something a little odd about these five everyday objects connecting so deeply with this young boy. Blanky makes sense. Even Lampy and Radio could form an intimate bond with whoever uses them.

It gets a little weirder with Kirby and Toaster. Surely this isn’t Rod’s special toaster. It’s the family toaster. So why does Toaster feel such a special bond with Rod over anybody else in the family? And hey, nobody loves toast more than me, so if Rod was just snacking on toast and Pop-Tarts left and right, I get it. But Kirby? What kid loves vacuuming? The movie still works, which is a real testament to the filmmakers’ talent. But they do throw in little mental roadblocks that the Toy Story movies simply didn’t have to deal with.

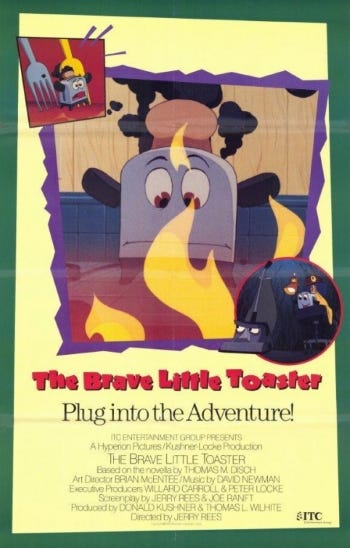

Rees, Wilhite and the rest of the filmmakers were justifiably proud of The Brave Little Toaster, made for a fraction of the cost and time as the typical Disney animated feature. They premiered the film in Los Angeles in July of 1987. While they already had a deal in place with Disney for television and home video distribution, Wilhite hoped to secure a theatrical release. He began submitting the film to festivals including Sundance, where it became the first original animated feature screened in competition.

The Brave Little Toaster was a hit at Sundance in January of 1988. Jerry Rees recalls members of the jury approaching him before the awards were given out to tell him that many of them felt his was the best movie at the festival. Unfortunately, nobody was going to vote for it because it was a cartoon. That year’s Grand Jury Prize went to something called Heat And Sunlight, which I can pretty much guarantee you’ve never even heard of, much less seen. At least Rees was in good company. John Waters’ Hairspray lost, too. Rees did receive a Special Jury Recognition, which is one of those weird consolation prizes they hand out when they don’t know what else to do with your movie.

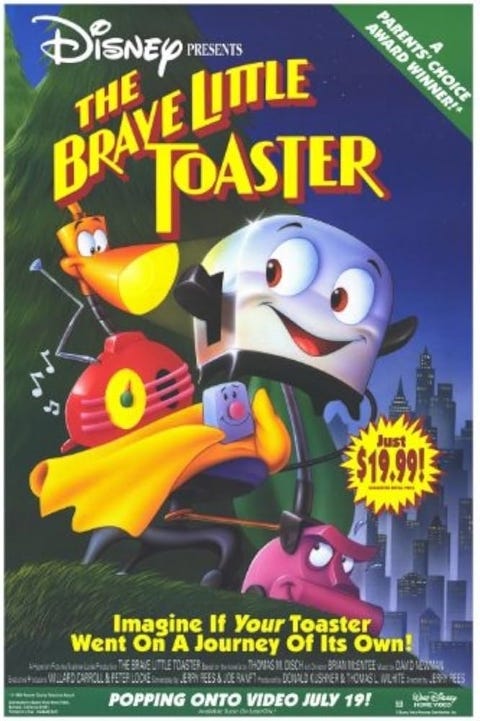

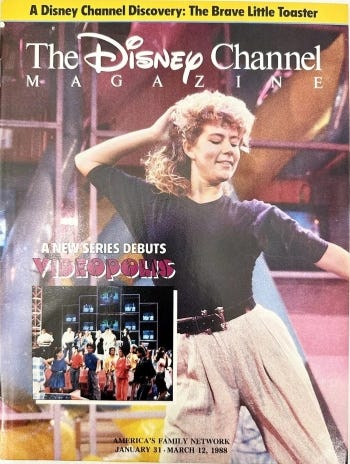

The festival buzz helped attract arthouse distributor Skouras Pictures, who planned on booking the film in independent theatres nationwide. But of course, none of this escaped the notice of the Mouse. Disney saw the momentum building behind The Brave Little Toaster and abruptly moved its Disney Channel premiere up to February 27. That killed the Skouras deal and any other chances of a wide theatrical run. Wilhite kept playing the festival circuit and got a few theatrical engagements on his own but most of the country only got to see The Brave Little Toaster on TV. Adding insult to injury, it wasn’t even featured on the cover of the Disney Channel programming guide. That spot went to the now-forgotten dance show Videopolis.

The Brave Little Toaster is one of the great underdog success stories in animation. It’s a surprisingly deep and poignant story told with real heart. The shadow of its legacy will continue to be felt in this column for a long time. Nearly everyone involved with the making of the film will be back in some capacity, including Jerry Rees over on the Touchstone side. Joe Ranft and Brian McEntee will both return and we’ll see plenty of work from the film’s animators, including Kirk Wise, Kevin Lima, Rob Minkoff and Mark Dindal.

Disney may still hold a bit of a grudge over the film’s success. While its later sequels, The Brave Little Toaster To The Rescue and The Brave Little Toaster Goes To Mars, are both streaming on Disney+, the original is conspicuously absent. This is a real shame. As long as the studio continues to hang on to the film’s rights, it should really acknowledge what some of its most talented alumni were able to accomplish on their own. It’s long past time for Disney to give this Toaster its due.

VERDICT: What should we call this…a Hyperion Plus? A Non-Disney Plus? Whatever. It’s a Plus.

I am fond of this movie for all the reasons you mentioned. It is a shame that it isn't readily viewable by kids today.