Disney Plus-Or-Minus: The Great Mouse Detective

The failure of The Black Cauldron was a devastating, near-fatal blow to Walt Disney’s storied animation division. Jeffrey Katzenberg, the studio’s new chairman, hated the ambitious fantasy and couldn’t understand how his predecessors allowed the production to drag on so long and cost so much. If animation was to continue to have a place at Disney, which was by no means guaranteed, Katzenberg demanded significant changes to the way these films were made. He began instituting these changes right away with a project that had already been in development for several years before his arrival: Basil Of Baker Street or, as it came to be known, The Great Mouse Detective.

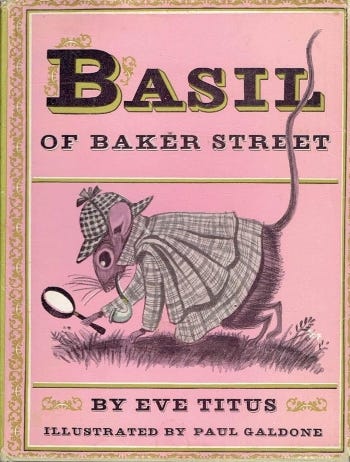

The original Basil Of Baker Street story, a charming Sherlock Holmes riff about a mouse detective and his Watson-like partner and biographer, Dr. David Dawson, was written by children’s writer Eve Titus and illustrated by Paul Galdone. It was published in 1958. Titus and Galdone followed it with four more Basil adventures, published between 1964 and 1982. Galdone died in 1986 and Titus herself passed away in 2002. The series was revived by a new creative team in 2018, with the most recent installment coming out in 2020.

Longtime Disney layout artist Joe Hale was responsible for bringing the series to Disney’s attention during the production of The Rescuers. Everyone liked the idea of doing an animal version of Sherlock Holmes, much as they’d done a few years earlier with Robin Hood. But since they were already working on a mystery-adventure starring a bunch of mice, Basil was placed on the backburner.

The project collected dust until 1982 when animator Ron Clements dug it out. Clements had been working his way up through the ranks, becoming a supervising animator on The Fox And The Hound. After that, he was paired with John Musker to work on The Black Cauldron. Musker and Clements were not a good fit for that project and they were eventually pushed out of that film’s revolving door of artists and animators.

Finding he had some unexpected time on his hands, Clements teamed up with artist Pete Young to take a crack at Basil. Clements was a big fan of Sherlock Holmes. Back in 1972, before he’d even arrived at Disney, he’d made an animated short starring the great detective called Shades Of Sherlock Holmes. Clements and Young took their pitch to then-president Ron Miller.

Going in, they already had at least two things in their favor. One was that the project had been kicking around for a little while, so Miller at least had some familiarity with it. But the other was that Clements, Musker and Young were not the only folks at Disney who weren’t entirely sold on The Black Cauldron. Miller needed to hedge his bets in case that whole thing fell apart. He okayed Basil as a potential alternative to the dark, megabudget fantasy.

With Clements and Young leading the story team, Miller assigned Musker and Burny Mattinson to direct. Mattinson had made an impression with his initiative shepherding his pet project, the short Mickey’s Christmas Carol, to the screen. After that film’s success, it made sense to see what he could do with a feature. The fact that Mattinson had also been a part of the anti-Black Cauldron contingent probably didn’t hurt.

As usual for a Disney animated feature, work progressed at its own, somewhat leisurely pace. Characters were developed, story ideas and plot points were tossed in and tossed out, countless sketches were drawn, thrown away and redrawn. It doesn’t appear that the story team took any specific inspiration from Titus’ books apart from the general premise and characters. Those may have come from Eve Titus (or, perhaps more accurately, from Arthur Conan Doyle through an Eve Titus filter) but the plot was pure Disney.

Production on the film probably could have carried on for another few years if it hadn’t been for the big shake-up at the executive level. Suddenly Ron Miller was out and Michael Eisner and Katzenberg were in. After the debacle of The Black Cauldron, they demanded to see what else they were working on. The team hadn’t even started to animate the film, so they did an old-fashioned storyboard presentation for their new bosses, walking through the entire film beat-by-beat, drawing-by-drawing in a meeting that lasted over three hours. It did not go well.

Neither Eisner nor Katzenberg had enough experience with animation to make heads or tails of what they’d seen. The only real impression Katzenberg left the meeting with was that he’d found the whole thing much too slow and boring. He wanted them to make significant rewrites to the story, just as he’d wanted them to do on The Black Cauldron. But in that case, it had been too late to do anything about it. This time, they could still turn the ship around.

There was even more good news. Katzenberg had been appalled by the cost of The Black Cauldron, so he promptly slashed Basil’s budget in half. To top it all off, he pushed up the film’s intended release date from Christmas 1987 to July 1986. This gave them one year to make a whole lot of changes with less time and less money. Oh, and one more thing. Katzenberg decided he wanted the animation building for his burgeoning live-action division. The entire department, which had been whittled down to a skeleton crew of less than 200 people, was exiled to a shabby warehouse in Glendale.

With Ron Miller gone, the film also found itself without a producer. The job went to Burny Mattinson, who took one look at the accelerated schedule and realized there was no way he was going to be able to produce and direct. To help fill the gap, veteran Disney animator Dave Michener and Ron Clements were both promoted to director, bringing the total number of credited directors to four.

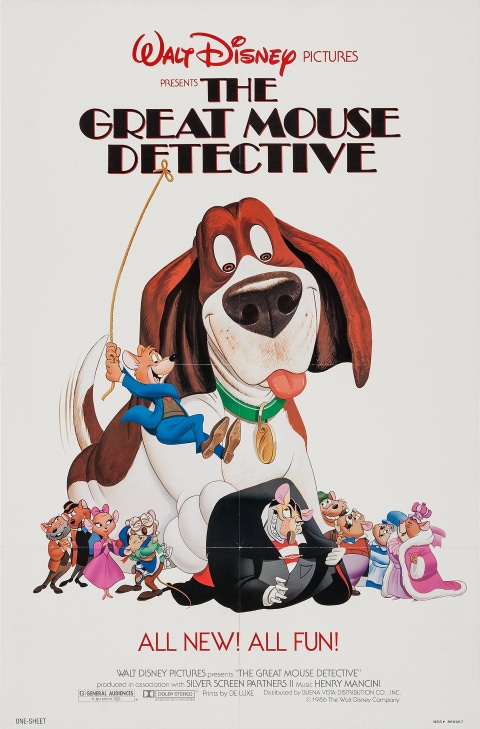

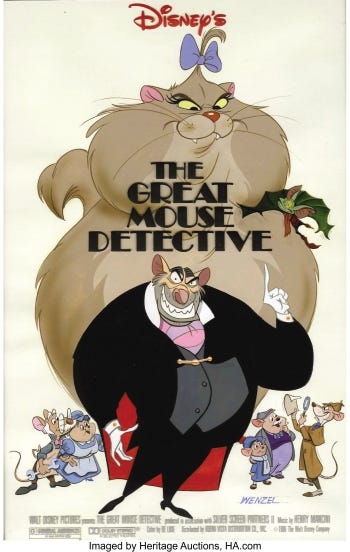

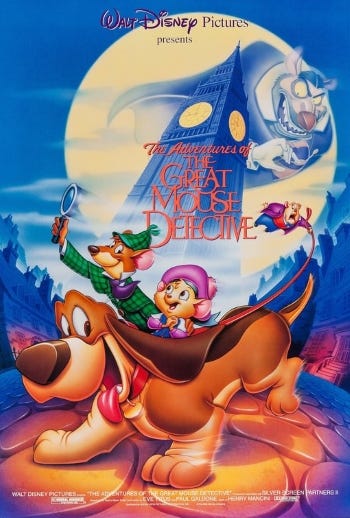

The executive team had one more indignity to throw at the production team on their way to the finish line, although this one came from Peter Schneider, the newly installed vice president of animation and Roy E. Disney’s second-in-command. Throughout the entire process, the movie had always been titled Basil Of Baker Street. Then, in late 1985, the Steven Spielberg-produced Young Sherlock Holmes was released to considerable hype but audience indifference. Suddenly, Schneider’s marketing department wasn’t too sure how closely they wanted Disney’s film to be associated with Sherlock. He also hated the name “Basil”, fearing American audiences wouldn’t be interested in such a quintessentially British name. Henceforth, the film would be titled The Great Mouse Detective.

Everyone working on the picture thought this was just about the stupidest idea they’d ever heard. But sometimes when the boss tells you how a thing is going to be, there’s not much you can do about it. However, it did result in a fairly hilarious bit of silent protest with an anonymous interoffice memo supposedly from the desk of Schneider decreeing that the Disney classics would also be retitled to go along with the new direction. Some of the “new titles” included The Girl With The See-Through Shoes, Two Dogs Fall In Love and Puppies Taken Away.

Despite all this behind-the-scenes drama, Mattinson, Musker, Clements and Michener got to work doing what they do best. Their story focused on the first meeting between Basil and Dr. David Q. Dawson at 221½ Baker Street, right beneath Sherlock’s place. Their first client is a young girl named Olivia whose father, a toymaker named Flaversham, has been abducted by a peg-legged bat named Fidget. Basil is all too familiar with Fidget, the sycophantic flunky of his archnemesis, the evil Professor Ratigan.

With the help of Sherlock Holmes’ basset hound, Toby (a dog Holmesians will recognize from Doyle’s The Sign Of The Four), Basil, Dawson and Olivia pick up Fidget’s trail. They find him collecting supplies for Ratigan’s master plan. While they’re able to pick up a valuable clue, they lose Olivia.

Basil and Dawson track her down to Ratigan’s lair, which turns out to be an elaborate deathtrap. The villain leaves them to their fate but not, of course, before explaining his sinister plot. Flaversham has constructed a clockwork replica of the Mouse Queen, who will be celebrating her Diamond Jubilee that evening. Ratigan intends to replace the real Queen with his robot and use her to declare himself the Supreme Ruler of all Mousedom. Fortunately, our intrepid heroes escape and come to the rescue, culminating in a spectacular showdown high above London in and around Big Ben.

That climactic sequence is worth singling out as it marked Disney’s most extensive use of computer-generated animation to date. Even today, it’s an impressive piece of work, helped along by the fact that the CGI elements are things like gears and clockworks that computers are exceptionally good at rendering. You might expect it to look primitive by today’s standards. It does not. There’s something genuinely thrilling about seeing these little hand-drawn characters race around on computer-generated backgrounds. The combination makes the chase feel both more real and surreal at the same time.

Considering the limitations they were forced to work under, it would have been understandable if The Great Mouse Detective had turned out a little rushed and slipshod. Instead, it’s one of the most purely enjoyable movies Disney had produced in years. Whether it was the hastened production schedule or it was always built into the material, the movie just feels lighter on its feet than something like The Black Cauldron or even The Fox And The Hound. It zips right along with delightful characters, thrilling setpieces and an unforced charm. There’s not a lot of fat on this one.

The voice actors play a huge part in building that sense of fun. Barrie Ingham, primarily a stage actor with a handful of mostly British film and TV credits, is terrific as Basil, striking just the right balance of haughty superiority when things go right and tortured despair when they don’t. He’s perfectly paired with Val Bettin, who was actually from Wisconsin despite his impeccable British accent. The Great Mouse Detective was Bettin’s first voiceover gig but he’d go on to do a lot more, including the Sultan in Disney’s direct-to-video sequels The Return Of Jafar and Aladdin And The King Of Thieves.

Susanne Pollatschek brings a lovely naturalism to Olivia. After this, she evidently decided acting wasn’t for her. This remains her only screen credit. Olivia’s father, Flaversham, is instantly recognizable as Scrooge McDuck himself, Alan Young. Fidget’s slightly sped-up voice isn’t instantly recognizable but it’s radio performer Candy Candido, a Disney veteran with credits in everything from Peter Pan to the Haunted Mansion attraction. And “appearing” as the human Holmes and Watson are Basil Rathbone, the quintessential Sherlock Holmes, courtesy of some archival audio from the 1960s, and Laurie Main, last seen in this column in Herbie Goes To Monte Carlo.

Of course, the real star of the show needs no introduction. The filmmakers were inspired to contact the legendary Vincent Price to play the evil Ratigan after watching the 1950 film Champagne For Caesar. The intent of the screening was to use star Ronald Colman as a potential reference point for Basil. Instead, they focused on Price’s supporting role and found their Ratigan. For his part, Price was eager to work with Disney (although he’d kinda sorta already done so, having narrated Tim Burton’s 1982 short valentine to the actor, Vincent). Here, he sounds to be having the time of his life, relishing the freedom of voice acting and even throwing himself into a couple of original songs.

Those two songs and the film’s score were composed by an equally legendary figure. Henry Mancini had been responsible for some of the most recognizable film music of the 20th century, including Breakfast At Tiffany’s and The Pink Panther, but he’d never done a full-length animated feature. Mancini’s music is a lot of fun, as is the movie’s third original song, “Let Me Be Good To You”, written and performed by Melissa Manchester. It's a little surprising that Disney never bothered to release a soundtrack album. When one finally came out years later, it was licensed to Varèse Sarabande.

The Great Mouse Detective made its July 2, 1986, release date. It didn’t do great right off the bat, coming in 9th on its opening weekend. But the movie had legs, thanks to some extremely good word of mouth and glowing reviews. It also probably didn’t hurt that families didn’t have a lot of options for younger kids that summer. Believe me, I remember having to ask to see a lot of R-rated movies over that vacation. By the time it left theatres, it had pulled in over $25 million, more than The Black Cauldron and a lot more than its budget.

Ordinarily, this probably would have been cause for celebration at the new Glendale facility. Disney Animation badly needed a win. But a few months later, another animated movie came out that soured their summer victory. An American Tail, the second feature from Disney defector Don Bluth and his first in collaboration with executive producer Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment, was released around Thanksgiving. It also got great reviews, had an Oscar-nominated hit single in “Somewhere Out There”, and did even better at the box office than The Great Mouse Detective.

The success of An American Tail would have been bad enough but I imagine what really stung was the fact that Bluth had teamed up with Spielberg. Spielberg was (and, presumably, still is) a fervent fan of classic Disney. In interviews, he would frequently talk about the influence Walt’s films, parks and comics had on him as a kid. He would make explicit references to them in his own films. John Williams’ score for Close Encounters Of The Third Kind quotes “When You Wish Upon A Star”. The climax of 1941 unspools during a screening of Dumbo.

It was clear that Spielberg loved and revered Disney’s history. But when he became interested in sticking a toe into animation himself, he went with Bluth. It was another sign that Disney was no longer the only game in town when it came to animation. If they were going to stand a chance of regaining some of their lost luster, it was going to take more than one moderately successful movie.

VERDICT: Don’t let that “moderately successful” comment fool you. If anything, this is an extremely underrated Disney Plus.

Like this post? Help support Disney Plus-Or-Minus and Jahnke’s Electric Theatre on Ko-fi!