Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg took the reins at Disney toward the tail end of production on The Black Cauldron. Apart from that, the only other movie the animation department was working on was Basil Of Baker Street or, as it came to be known, The Great Mouse Detective. So once they magnanimously decided that animation could continue to have a place at the studio named for one of the most famous animators of all time, they needed to figure out what they were going to do next.

Inspired by that great judge of talent and creativity Chuck Barris, Eisner and Katzenberg decided to bring over a technique they’d used before at Paramount. They summoned the animators to a Gong Show-style pitch meeting. Everyone was tasked with bringing two ideas to present to the new bosses. Second prize was a set of steak knives, third prize was you’re fired. OK, maybe that last part wasn’t true but it was certainly a more Glengarry Glen Ross way of working than the animators were used to.

A lot of ideas were shot down at that meeting, most of which have been lost to memory. Ron Clements pitched a version of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid and “Treasure Island in space”, both of which got gonged initially but eventually saw the light of day. Katzenberg saw enough potential in a couple ideas to ask to see a treatment but they didn’t make it much farther than that.

The only idea Katzenberg sparked to immediately came from story artist Pete Young, who suggested doing Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist but with dogs. Katzenberg loved the fact that it would be set in contemporary New York City and was a fan of both the book and its musical adaptation. Out of all the ideas pitched that day, Young’s Oliver twist was the only one to make Katzenberg say, “Yes, let’s do that.”

As was perhaps to be expected at this point, the development process was not easy. Pete Young was named head of story while directorial duties were assigned to Richard Rich, one of the directors of The Fox And The Hound and The Black Cauldron, and George Scribner. Prior to joining Disney, Scribner had been an animator on adult animated films like Ralph Bakshi’s American Pop and Heavy Metal before moving over to Hanna-Barbera, where he worked on such icons of the ‘80s as The Smurfs and Transformers. He’d joined Disney mid-decade and Oliver And The Dodger, as it was then titled, would be his first directorial credit.

The Disney animators and the new executives butted heads almost immediately. Eisner and Katzenberg had been thoroughly baffled by the visual story meeting they’d seen for The Great Mouse Detective. They were used to seeing things on paper in screenplay form. But Disney animation had never (or, at least, rarely) worked like that. They needed to develop the story drawing by drawing. Eventually, a compromise was reached, allowing the animators to work their way while screenwriters molded it into a script. As a result, the writing credits on Oliver & Company are lengthy even by Disney standards.

The story team included many names that should be familiar to animation fans: Joe Ranft, Kirk Wise, Dave Michener, Roger Allers, Gary Trousdale and Kevin Lima, among many others. The animation screenplay was credited to Jim Cox, Tim Disney and, of all people, James Mangold. Cox would continue to be primarily an animation writer, eventually leaving Disney to work on such films as FernGully: The Last Rainforest. Tim Disney was the son of Walt’s nephew, Roy E. Disney, who had recently been put in charge of the animation department. This was essentially an entry-level job for the youngest Disney. He’d soon leave the studio and begin producing and directing his own documentaries and live-action features.

As for James Mangold, yes, this is the same guy who went on to write and direct movies like Cop Land, Walk The Line and Logan. Surprisingly, Oliver & Company wasn’t even his first Disney credit. In 1986, he wrote an episode of The Magical World Of Disney called The Deacon Street Deer which seems to be his first produced work. He also has another animation credit, working on the story for Will Vinton’s TV special Claymation Easter. Mangold would later take a side door back into Disney via Lucasfilm. His announced Star Wars movie didn’t pan out but he did inherit Steven Spielberg’s director’s chair on Indiana Jones And The Dial Of Destiny.

Before Oliver & Company could even start production, the project was dealt some harsh blows. First, Pete Young, whose idea the film had been in the first place, shockingly died at the young age of 37. This obviously caught everyone completely off-guard but Young had already started losing control of the story. Lots of ideas were being thrown at the wall and Young unenthusiastically had included most of them. One idea which had come from Roy E. Disney himself revolved around Fagin’s gang stealing a panda from the Central Park Zoo. The team worked on this idea for months before Katzenberg dismissed the whole thing as stupid.

The second near-catastrophe occurred in the wake of the disastrous reception of The Black Cauldron. After that movie flopped, a round of lay-offs hit the animation department. One of those to get the axe was director Richard Rich. Rich would be replaced by no one, leaving George Scribner the sole director of the project.

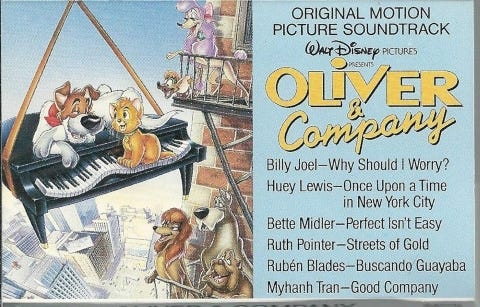

When the movie was still known as Oliver And The Dodger, it was not conceived of as a musical. Honestly, I can’t quite pinpoint exactly when the decision was made to push it in that direction. Regardless, the songs were incorporated in a somewhat unusual manner at Katzenberg’s request. Instead of a single unified vision, each song was written and produced by a completely different group of musicians. The result is an eclectic lineup that includes Dan Hartman and Charlie Midnight (“Why Should I Worry”), Jack Feldman, Bruce Sussman and Barry Manilow (“Perfect Isn’t Easy”), Dean Pitchford and Tom Snow (“Streets Of Gold”) and Rubén Blades (“Buscando Guayaba”).

While Katzenberg was assembling his musical dream team, his friend David Geffen suggested he meet with lyricist Howard Ashman. Geffen had produced Ashman’s off-Broadway musical Little Shop Of Horrors. Ashman, of course, will have a huge impact on this column very soon but his first contribution to a Disney movie was Oliver’s opening number, “Once Upon A Time In New York City”, cowritten with Barry Mann (who had cowritten the hit song “Somewhere Out There” for Disney rival Don Bluth’s An American Tail) and performed by a News-less Huey Lewis.

Considering how it was cobbled together, it’s surprising that the music in Oliver & Company is as cohesive and enjoyable as it is. Granted, your appreciation of it depends entirely on your tolerance for ‘80s pop. But the songs do exactly what they should, introducing and developing characters and setting the tone for a lively, enjoyable film.

Scribner and Katzenberg also thought outside the box when it came to casting. Billy Joel had never acted before outside of playing dress-up in music videos like “Uptown Girl”. This was a concern for Scribner, who auditioned the Piano Man over the phone. But he was surprised by Joel’s commitment to the part. Billy Joel hasn’t really acted again since Oliver & Company but he’s well cast as Dodger and his performance of “Why Should I Worry” is a highlight. It’s interesting that Joel himself didn’t write any songs for the movie. Maybe he was too expensive as a songwriter or perhaps he just wasn’t feeling it (Billy Joel’s songwriting muse has always been notoriously temperamental). A few years after Oliver & Company was released, Joel contributed a cover of “When You Wish Upon A Star” to the Disney tribute album Simply Mad About The Mouse.

One of the reasons Billy Joel agreed to do the movie was that he’d recently had a daughter, Alexa Ray Joel, and wanted to do something she would enjoy. Impressing the kids was also a consideration for Cheech Marin, who voiced Tito, the chihuahua. At the time, Marin was still in the process of stepping away from the stoner comedy of Cheech and Chong, so his involvement in a Disney movie still raised a few eyebrows. This was his first high-profile voice gig but far from the last. He’ll be back in this column repeatedly.

Georgette the poodle was voiced by Bette Midler, at the time four films deep into her lengthy association with Disney/Touchstone. I covered the first of those, Down And Out In Beverly Hills, last week in Touchstone Plus Or Minus and we’ll see plenty more of her on both sides. The movie’s primary human characters, Fagin and Sykes, were played by Dom DeLuise and Robert Loggia. DeLuise had already done some voice work for Don Bluth and he’d continue to be a regular for the former Disney animator but this was surprisingly his only contribution to a Disney film. Loggia, on the other hand, started his career at the studio, starring in the Disneyland series The Nine Lives Of Elfego Baca back in the 1950s. He’ll turn up again on the Touchstone side.

The voice of Oliver, 12-year-old Joey Lawrence, wasn’t a star yet when he recorded his part. But he’d soon become a teen idol on the sitcom Blossom, coproduced (probably not coincidentally) by Touchstone Television. The movie’s other child actor was Natalie Gregory as Jenny, the poor little rich girl who adopts Oliver. Gregory was a busy little girl, appearing in lots of television throughout the ‘80s, but didn’t stay in the business much past adolescence, although she did appear in the Walt Disney World attraction Cranium Command.

On its initial release, critics were lukewarm at best on Oliver & Company. Siskel and Ebert’s review was fairly indicative of the response. Siskel didn’t care for the picture at all but Ebert gave it a marginal thumbs up. But when pressed on what exactly he liked about it, Roger half-heartedly mentioned a few things before admitting, “I don’t know.” Not exactly a four-star rave.

I think critics missed the boat on this movie. Oliver & Company has always worked for me and it hooks me from the opening sequence. I cannot make it through “Once Upon A Time In New York City” without a lump in my throat and tears in my eyes. Part of that is the song but most of the work is done by the beautiful character animation on Oliver. It’s heartbreaking to see him left behind while the other kittens in his litter find homes. To be clear, I was 19 years old when this movie came out, not 6. I guess I’ve always just been a sucker for cats.

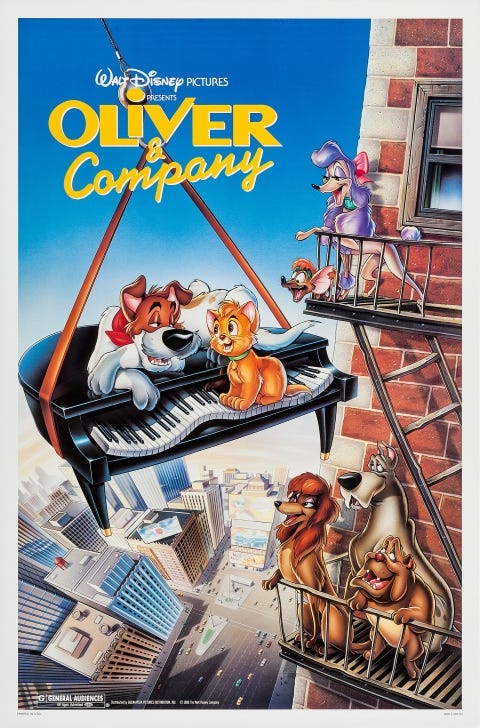

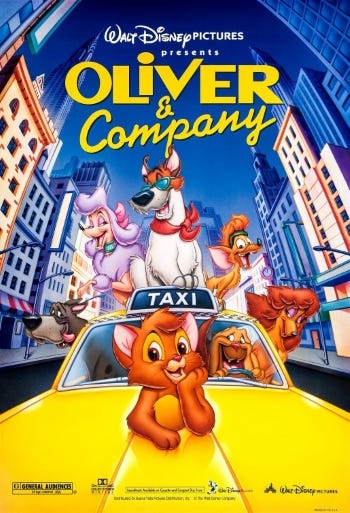

The animation in Oliver & Company is often dismissed but I find it unique and beautiful. Computers were playing a bigger role, which resulted in fluid camerawork and sleek designs for Sykes’ car and the staircase in Jenny’s townhouse. But the character work and a lot of the backgrounds have a scratchy, Xeroxed quality similar to One Hundred And One Dalmatians (Pongo himself makes a quick cameo, as do some other famous Disney dogs). The combination shouldn’t work but it does, giving the picture’s New York a gritty, lived-in quality you don’t often associate with Disney animation.

To say Oliver & Company is loosely inspired by Dickens’ novel is putting it mildly. The picture lightly skims the surface of the book. But there is still a darkness around the edges, exemplified in that opening scene, the surprisingly grim fate of Sykes, and even Jenny’s absent parents missing her birthday. Despite this, the film’s overall tone is warm and joyful. The music is lively, the comedy lands, and the emotional bonds between the characters hit home. Gene Siskel and other critics complained that Oliver & Company didn’t live up to Disney’s legacy of animated classics. Perhaps it doesn’t but I’d argue it gets a lot closer than it’s usually given credit for.

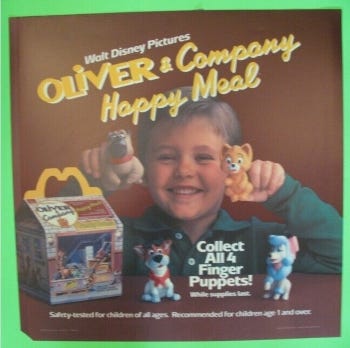

Oliver & Company opened in theatres on November 18, 1988, the same day as Don Bluth’s The Land Before Time. This was the first time the two rivals had gone head-to-head at the box office. Bluth’s dinosaurs won round one, opening in first place with over $7 million compared to Oliver’s $4 million in fifth. The two movies remained virtually neck and neck throughout the holiday season but eventually, Oliver began to pull ahead. At the end of their theatrical runs, Oliver & Company ended up earning around $53 million, a bit more than Bluth’s $48 million.

George Scribner never directed another Disney feature. His next project was the Mickey Mouse short The Prince And The Pauper, released with The Rescuers Down Under in 1990. But after leaving The Lion King, a project he was originally supposed to direct, he left Walt Disney Feature Animation entirely to join the Imagineering crew, working on such attractions as Mickey’s PhilharMagic.

Despite its financial success, Oliver & Company is too often overlooked for its role in helping revive Disney animation. It is admittedly a transitional film, bridging the gap between the turbulent ‘70s and ‘80s and the Disney Renaissance of the 1990s. But I feel it deserves more respect than its outlier status grants it. This is a vibrant, happy movie that I always enjoy revisiting. And if that’s not enough to make it a classic, I don’t know what does.

VERDICT: Disney Plus

Funny enough, I don't remember many kids talking about this movie at all at the time, but everybody was talking about THE LAND BEFORE TIME. So whether OLIVER beat it at the box office or not made no difference on my playground.

I just watched this movie for the first time yesterday. Not the best, but a good film with great music